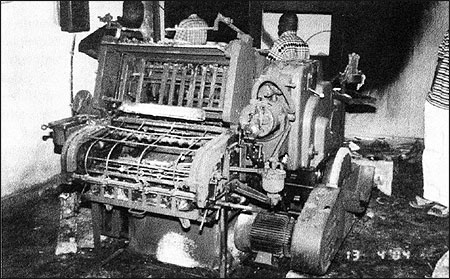

The Independent’s printing press was burned in 2004 as part of a campaign to stop the biweekly newspaper from being published.

Gambia was once known as the "smiling coast," a place full of sunshine, welcoming with generosity of spirit. Home to the African Commission on Human and People’s Rights, it was a bastion of democracy in a continent beset by military coups and despots. It boasted a long tradition of press freedom and celebrated in June 1994 with a journalism training workshop in which I took part that was sponsored by the U.S. Embassy.

A month later everything changed. A group of junior army officers overthrew the 29-year long government of Sir Dawda K. Jawara. Soldiers installed one of their own, Yahya Jammeh. He promised to rid the country of corruption and run a decent, open government. It wasn’t long before his promise of transparency became a transparent lie.

Attacks on news organizations started almost immediately. There were raids on the independent press, and journalists were subjected to harassment and deportation. Because the country had few private media outlets, a change of ownership — and subsequently a change in its approach to news reporting — at the Daily Observer, one of the nation’s bigger papers, narrowed the outlets for independent newsgathering still further. Against this backdrop, I started a biweekly called The Independent, which hit newsstands in July 1999 and soon became the fastest growing newspaper in readership and popularity. With its Monday and Friday editions, circulation grew to 10,000, with an estimated readership of more than 30,000.

Less than a month after The Independent was launched, the National Intelligence Agency (NIA) raided its offices, and many journalists were arrested and detained. Authorities claimed the paper had not fulfilled all of its obligations to be allowed to operate. This came despite the paper’s managing editor having been given permission by officials in the government. For two weeks, the paper ceased publication. Once it began again harassment and intimidation continued with unrestrained regularity. I was arrested and detained as the authorities attempted to investigate the paper’s source of funding. Even female typesetters were bundled to the NIA headquarters in Banjul.

In July 2000, I was arrested and detained by the NIA after I published an article about a hunger strike at the Central Prison. Asked to reveal my sources, I refused. Eventually I was released on bail. In August, however, I was arrested again, and this time placed in solitary confinement where I was subjected to physical and mental harassment and psychological torture. Officers forced me to strip naked, and I was kept in the empty cell. Mosquitoes were everywhere, and the floor was damp with urine. Many of the prisoners in this jail were sick, and I contracted pneumonia and malaria. During my confinement, I was held incommunicado and was not allowed to talk to anyone, including my family or a lawyer.

A month later I was arrested again when The Independent published a story with news that the vice president had remarried. The government was embarrassed by the story because after a spouse dies it is customary for a person to wait one year before remarrying. Hardly a week passed when the newspaper and staff members were not harassed by NIA authorities or by people identified with the ruling regime.

In October 2003, The Independent’s premises were set on fire for the first time, and the newsroom was partly destroyed. A security guard was attacked and hit with an iron bar. I began receiving death threats. By January 2004, the situation had deteriorated even more, when I received a letter signed by a group called the "Green Boys" threatening to kill me and destroy my newspaper because of our reporting. Soon the printing press was burned. One source told the National Assembly that two officers of the Gambian National Guard were among those who attacked The Independent, yet no investigation of this crime has been undertaken.

After The Independent’s press was burned, the Daily Observer printed the paper for us. Soon, however, I was notified that the arrangement had been terminated; no reason was given. For two months, The Independent did not publish, but its press run was resumed by a skeleton staff working in Gambia and a few determined reporters and editors elsewhere. Its circulation dropped almost 50 percent, and it was printed on a smaller sheet by press operators who prefer to remain anonymous. Other Gambian printing and publishing outlets have refused to print the newspaper on contract because, I believe, they have either been threatened not to print The Independent or fear that they or their presses could be attacked as well.

The Independent’s newsroom was partly destroyed when it was set on fire in 2003, another attempt to stop its publication.

Threats and Murder

When it began, The Independent had 25 staffers and freelancers. About four and a half years later (after I’d received a personal death threat in the letter signed by the "Green Boys" along with a threat to destroy The Independent), many of the newspaper’s senior reporters and support staff have left the paper. Many have also left the country, as some of its leading journalists have sought political asylum in Europe and the United States.

In June 2004, officers arrested and detained me for three hours without charge, allegedly for publishing a story that two persons were killed in a Gambia-Senegal border clash following a violent football match between the two countries. Attacks on journalists continued. In August 2004, Demba A. Jawo, then-president of the Gambia Press Union, received an anonymous threat at his house that referred to critical reporting by Jawo and other members of the independent press against President Jammeh and his government. The letter promised to teach "one of your journalists a very good lesson." Three days later, unidentified persons set on fire the house of BBC stringer Ebrima Sillah, but he escaped unharmed. (In July, the BBC in London had received a letter that accused Sillah of biased reporting against Jammeh and threatened an attack on him.)

President Jammeh’s hostility towards journalists is what pushed members of Parliament to find ways to muzzle the press. In 1999, the Gambian Parliament prepared a bill to create a National Media Commission with quasijudicial powers including registering private media houses and journalists, to revoking licenses, issuing arrest warrants for journalists, and fining or even sentencing journalists to imprisonment. This commission would also be able to force journalists to reveal their sources. Strict penalties would be assessed if journalists did not comply with the new law, including imprisonment and heavy fines.

In 2002, this bill was enacted into law. Deyda Hydara, editor of The Point newspaper, and I knew that this law was inimical to a free press. We partnered with the Gambia Press Union to challenge it and hired a lawyer to contest the legislation.The lawsuit reached the Supreme Court in 2003 and challenged the constitutionality of the National Media Commission Act of 2002. Two hearings were held before the state counsel — the lawyer for the government — declared that the government was going to repeal this act. We did not want to withdraw our case because even if this law was repealed, we wanted a final declaration by the court that it was unconstitutional. This lawsuit is pending before the Supreme Court, which sits every six months. We are awaiting a final decision while we look for sources of funding for our lawyer to continue to pursue the case.

The government then proposed an equally draconian set of laws — the Newspaper Act and the Criminal Code Amendment Act. The Newspaper Amendment Act forces private newspapers and journalists to execute bonds in the order of 500,000 dalasi, or approximately $20,000, an amount that is four times the previous bond requirement and so excessive that it will have the effect of shutting down the private newspapers. The act also requires newspapers to register with the Registrar General. The Criminal Code Amendment Act expands the definition of libel and provides for harsh imprisonment terms of not less than three years in jail. This legislation was passed by the Gambian National Assembly in December 2004.

Hydara and I prepared to launch another lawsuit against these laws. By doing this we became targets of the state; we were seen as using the courts to justify our actions in exposing the dictatorial tendencies of the government. Soon the state developed a different tactic of silencing us, by destroying our properties and by murder. In December 2004, an unidentified assailant shot and killed my friend, Deyda. Two members of his staff also were injured. The government has not investigated his death.

Hydara’s assassination is evidence of the extent to which the Gambian government is prepared to go in order to silence its opponents. Actions taken against the independent press demonstrate the intractable view of President Jammeh that all journalists are criminal illiterates who would be best "buried six feet deep." It reveals, too, the impunity of those who murder people who dare to oppose the government. Such actions expose the rotten heart of the government in my beautiful country. If a man like Deyda Hydara can be murdered for the proper execution of his profession, then no one can sleep peacefully. Nobody will be spared.

Is it possible to act courageously as a journalist in Gambia today? Perhaps, though it is surely true that our experiences — with the murder of our brave friend, the torching of ourprinting press, the imprisonment and torture and threats that reach us and do not abate — have taught us that there are limits to what we, and our family members, can endure, especially when we are not able to do the work we know is ours to do. As intimidation builds, stress finds less and less relief as every possible effort to push on and report and publish is exhausted. When time and time again those efforts are foiled by government intervention, when our personal safety is threatened, the courage to seek another way and do so from another place can become the force of change.

Self-censorship by the press in Gambia is a real possibility. Hydara’s death sparked a climate of fear that could lead to fewer voices critical of government. Families of journalists and independent media workers, even families of those who operate printing presses, now pressure their loved ones to refrain from overt criticism of the regime and to look for other employment. Even slight association with the independent media is dangerous.

But no amount of intimidation, death threats or attacks can cower me into silence or compromise my editorial policy. Though I now live in exile in the United States, my interest in learning and publishing the truth remains paramount. As a Gambian journalist, I am prepared for the dangers and risks, the trials and tribulations, and the aches and stresses of running a wholly independent newspaper such as The Independent. Yet even this spring, in March, plainclothes police officers stormed The Independent’s offices and arrested every member of my staff, as guards sealed off the newspaper. No reason was given for it being closed. Most of the staff was released after brief questioning, but two of my paper’s senior editors were held in custody for more than three weeks incommunicado and without any charges filed against them, which is against the laws of Gambia and the Universal Declaration of Human Rights. One of our reporters was then arrested and remains in custody, with no contact allowed. The Independent remains closed today because of the government’s actions against it.

A front page story about Gambia’s president in a 2003 issue.

Alagi Yorro Jallow is cofounder and managing editor of The Independent in Gambia. He has twice won the Hellman/Hammett award, in 2000 and 2004, and also is the winner of the 2005 Canadian Journalists for Free Expression International Press Freedom Award. He will be a 2007 Nieman Fellow.