Companies like Google and Facebook, whose offices are shown here, are now considered essential to the journalism industry

The first time I visited Facebook’s office in Washington, D.C., I was asked to sign a nondisclosure agreement. I didn’t.

Then there was the time I got through an entire interview with a product manager at Apple, only to be told, after the fact, that it was presumed to be on background. “Everyone knows this is how we do things,” a spokesman explained apologetically. Nope.

Just before Christmas a couple years ago, HP sent me a bright pink laptop I’d never asked for. I sent it back.

I’ve been offered iPhones, international plane tickets, and more gadgets than I can count. “Can also send over a draft press release and a big ol’ bottle of wine for sitting through my email ;),” one PR person wrote in March.

This is what it’s like to be a technology reporter in 2016. Freebies are everywhere, but real access is scant. Powerful companies like Facebook and Google are major distributors of journalistic work, meaning newsrooms increasingly rely on tech giants to reach readers, a relationship that’s awkward at best and potentially disastrous at worst. Facebook, in particular, is also prompting major newsrooms to adjust their editorial and commercial strategies, including initiatives to broadcast live video to the social media site in exchange for payment. Other social platforms are becoming publishers, too, including Snapchat Discover and Reddit, which recently posted job listings for an editorial team.

The lines are blurring, in some cases dramatically, between what it means to be a media company and what it means to be a technology firm. The leaders of some websites with robust newsrooms, like BuzzFeed, even refer to themselves as tech companies first, journalism organizations second. Cash-rich media start-ups and at least one legacy newspaper, The Washington Post, are owned by titans of tech.

Silicon Valley’s leaders aren’t uniformly champions of the press, however. Peter Thiel, the venture capitalist and PayPal co-founder, poured $10 million of his own money into the lawsuit that eventually bankrupted Gawker Media Group last spring. Univision bought Gawker for $135 million in August, and shut down its flagship site, Gawker.com, soon after. (Other sites in the Gawker network, like Jezebel and Gizmodo, are still running.) The Gawker-Thiel showdown was a dispute in its own right, but it can also be viewed as a microcosm of the broader tension between media companies and technology companies, a relationship so strained that, as Nicholas Lemann wrote in The New Yorker, the journalism industry should be readying itself for a “protracted war.”

The lines are blurring, in some cases dramatically, between what it means to be a media company and what it means to be a technology firm

Against this backdrop, tech reporting presents one of the most profound accountability challenges in modern journalism. Who is best served by the coverage we have? And is it the coverage we deserve and need?

“Accountability reporting in Silicon Valley, like accountability reporting anywhere, is difficult—and essential,” says David Streitfeld, a technology reporter for The New York Times. “There is no great tradition of accountability reporting in tech, no exalted predecessors the way there is with, say, White House reporting or municipal reporting. There is no Woodward and Bernstein or Kate Boo of tech reporting.”

Tech coverage as we know it today got its start in the early 1980s, not from some investigative impulse but because the age of personal computing was just beginning and newspapers suddenly began selling a lot of tech-related ads. John Markoff, a long-time technology reporter for The New York Times, remembers the original culture of Silicon Valley as open and collaborative—even welcoming to journalists. In the early ‘80s, Markoff had access to the Homebrew Computer Club, a legendary hobbyist group whose members included the technologists who would go on to run Silicon Valley. Steve Wozniak, the co-founder of Apple, first shared his design for the Apple I computer at a Homebrew meeting in 1976.

“A wonderful thing about the Homebrew Computer Club is every computer company would come together,” Markoff recalls. “It was this random access period where people would share corporate secrets. This was like dying and going to heaven for a young reporter. But it was the original culture of Silicon Valley.”

Over the next few decades, the people running the tech sector went from occupying a niche cultural and economic space to being some of the most powerful business leaders on the planet. And the culture and influence of Silicon Valley changed dramatically. “Early on, Apple was fringe,” says Kevin Kelly, founding executive editor of Wired magazine. “It was nerdy-techy. The difference now is that these companies are the most profitable companies in the world. This is no longer the sideshow; this is the main show.”

Though Apple was at the center of an earlier open culture in Silicon Valley, it was also the company that prompted a reversal. Steve Jobs refined the art of the product surprise, generating enormous buzz for Apple by hosting keynotes where such announcements were hotly anticipated. At times, the outsized coverage of such events can seem as much a product of fan culture as it is journalism designed to serve that culture.

It’s also a journalistic approach that incentivizes limited access. Silicon Valley’s culture of secrecy comes, too, from the publishing power the Internet offers. Tech giants, like political candidates, no longer rely solely on the press to get out their message.

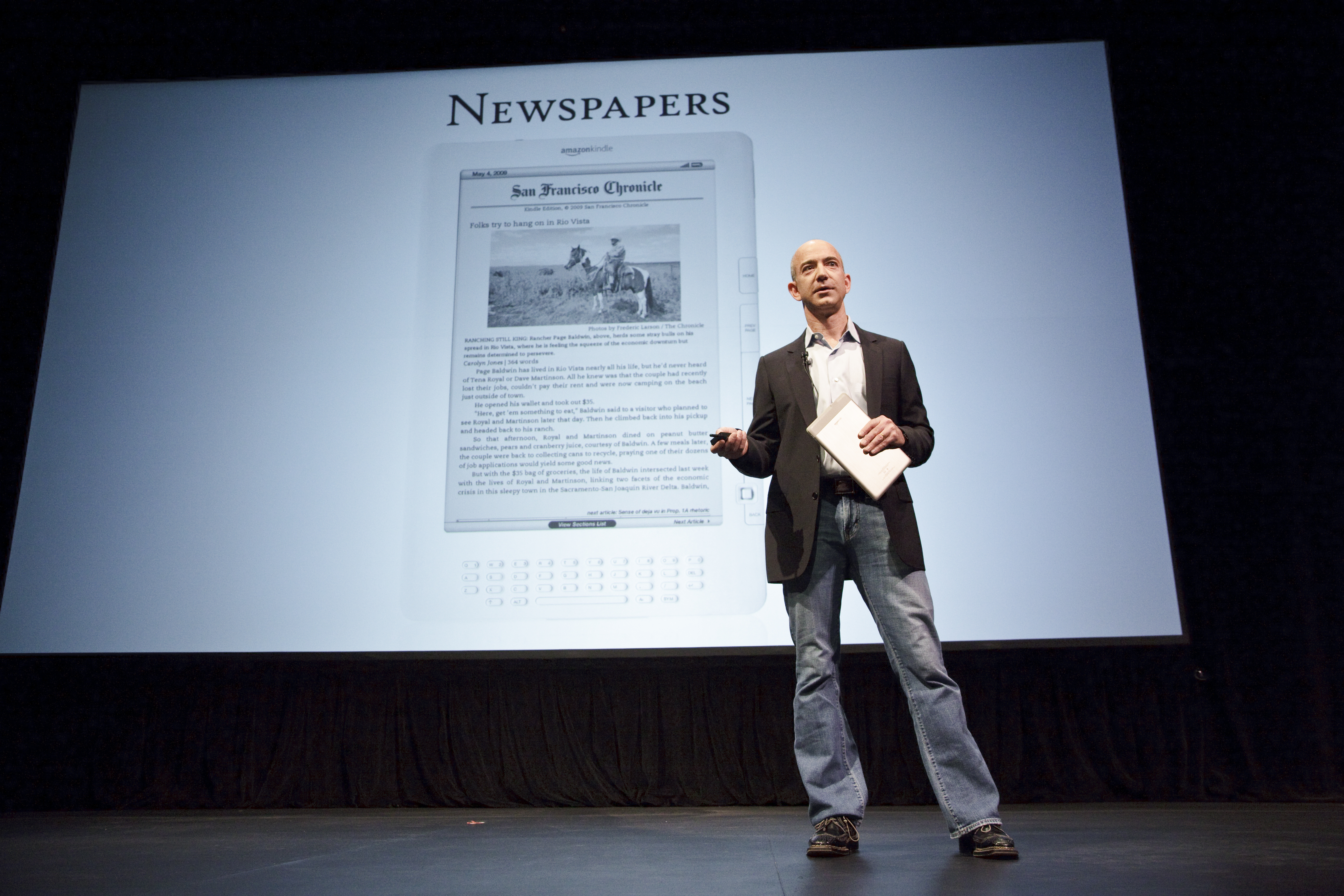

Amazon founder Jeff Bezos's ownership of The Washington Post raises questions about the extent of his editorial involvement in the paper

In turn, some of the world’s most powerful companies end up dictating a startling degree of coverage about them—because reporters often rely solely on information released by those companies, and, with some key exceptions, get few opportunities to question them. “It’s why a company like Google can dazzle people with the promise of some technology that’s really not ready yet,” says John M. Simpson, former deputy editor of USA Today and privacy project director for the nonprofit advocacy group Consumer Watchdog, where he focuses on Google. Compared with a crowded field of journalists covering Google, for example, Simpson has been one of the most prominent critical voices of the company’s Self-Driving Car Project.

It’s typical to see technology coverage that simply aggregates directly from a tech company’s blog—the modern-day equivalent of a press release—with little or no analysis or additional reporting. One damning example of this lack of skepticism is evident in the early, glowing coverage of Theranos, the health-technology company that said it had developed a cheap, needle-free way to draw and test blood. It wasn’t until last year that an investigative reporter from The Wall Street Journal, prompted by a sunny New Yorker profile of the Theranos founder, began to ask serious questions about whether the technology actually worked the way Theranos claimed it did. That reporting, from John Carreyrou, encouraged other reporters to be more skeptical, too, and ultimately led to a federal criminal investigation into whether the company misled investors and regulators about the state of its technology.

Investigations like Carreyrou’s—or getting inside the grueling corporate culture at Amazon, as The New York Times did last year; or detailing Google’s powerful but hidden lobbying efforts, as The Washington Post has; or contextualizing the cultural complexities of programs like Facebook’s Free Basics, as I’ve tried to do; or establishing a drumbeat of smart, in-depth coverage of the fight between Apple and the F.B.I.—is the only way to begin to understand the complex social and political impact of technology.

Technology companies “are all dedicated to revamping our daily existence,” says Streitfeld, who reported and wrote the Amazon piece for the Times with Jodi Kantor. “What happens when they succeed? Who loses? When they stumble, like Facebook in India, what does it mean? The rise of tech is, in my opinion, the great story of our time.”

Adds Kantor: “Technology companies are in the vanguard. They’re determining where the culture is headed. It’s where the culture is made, and they also let us look into our own futures.”

For their Amazon story, Kantor and Streitfeld interviewed more than 100 current and former Amazon employees. Kantor says she listened more than spoke in interviews with Amazon workers, and that stories just poured out of people. The memorable anecdote about people often crying at their desks, she says, came up repeatedly, and not just from the person they ultimately quoted. “I was taught long ago as a young journalist that the best stories are often investigating something that is lying around in plain sight,” Streitfeld says. “In this case, Amazon had said—boasted even—from the very beginning that it was an incredibly demanding place to work. All we did is ask, what does that mean?”

A major reporting obstacle was penetrating the culture of secrecy. LinkedIn proved to be a crucial source, one Streitfeld says he combed for hours: “It’s like a corporate X-ray.” All in all, Streitfeld and Kantor spent more than six months—a luxury, even at the Times—reporting the story, which generated enormous public attention as well as a swift rebuke, in the form of a PR counter-narrative published on Medium. Representatives from Amazon—as well as Google, Uber, Apple, and Facebook—either declined requests for interviews for this story or did not respond at all to those requests.

“The biggest challenge to producing a story like the Amazon piece, or any reporting about the tech community that challenges the community’s idea of itself, is that tech wants, expects, and quite often gets upbeat pieces,” Streitfeld says. “There’s a sense, in too much tech reporting, that when you cross the bridge into Silicon Valley, you’re in a world where the old rules of journalism don’t apply. One of the biggest clichés of Silicon Valley is when they say, ‘It’s not about the money. We just want to change the world.’ Sometimes that even may be true. But that’s a reason for better coverage, not weaker.”

But many leading news organizations, even those with robust tech sections, aren’t devoting adequate resources to develop and sustain such coverage, according to Emily Bell, director of the Tow Center for Digital Journalism at Columbia Journalism School. “To actually cover technology properly,” Bell says, “it’s about society and culture and human rights. It’s about politics. This idea that you can have a Washington bureau where you don’t have somebody who really understands some of the issues in [computing] infrastructure or A.I., and how data is really political? They are new systems of power, and that’s one of the areas where I think news organizations have been slow.”

While Bell and others argue that a foundational understanding of how computers and the Internet work is essential for all reporters, true technology coverage isn’t limited to what’s in the tech section. Technology shapes business, culture, politics, education, and every other facet of daily life. Just look at the complexity of the fight between Apple and the F.B.I. over whether Apple should be required to unlock the iPhone owned by one of the shooters in a deadly terrorist attack in San Bernardino, California. (Eventually, the F.B.I. said it was able to unlock the device without Apple’s help.)

“There’s terrorism, there’s technology, there’s Apple, there’s the F.B.I, Obama weighs in,” says Pui-Wing Tam, the New York Times editor who coordinated the paper’s coverage of the dispute. “It just straddles all sorts of different things. It brings what had been a very theoretical debate about encryption and privacy into the real world.”

In some ways, covering a story as big as the encryption dispute is more straightforward than figuring out day-to-day or longer-term tech coverage. “It’s important to define covering technology really broadly,” says Kantor, “and not to think of it as covering a bunch of startups in Silicon Valley only.” She gives the example of a story she wrote about a piece of automated scheduling software, one that’s used by huge corporations like Starbucks, which was creating stress and chaos for low-paid workers. “Here was this piece of software that basically nobody’s ever heard of, really obscure, and yet it was controlling the lives of millions and millions of workers,” she says. Within 24 hours of the article’s publication, Starbucks announced it would change its scheduling practices.

“There’s a sense, in too much tech reporting, that when you cross the bridge into Silicon Valley, you’re in a world where the old rules of journalism don’t apply”—David Streitfeld, NYT tech reporter

For Kantor, covering technology means interrogating the ways technology affects people’s lives—a framework so broad that it has the potential to be as dizzying as it is liberating for journalists who have to decide what to cover.

Reveal, the website of the Center for Investigative Reporting, doesn’t have a technology section, per se, but it does cover technology, most of which falls within the realms of privacy and surveillance. For Fernando Díaz, a senior editor at the site, “having a narrower focus is a way to help leverage the knowledge an investigative reporter builds over time, but also a way to give the audience a certain consistency in terms of our coverage, that we’re dedicated to a specific subject.”

For instance, Reveal has reported about a secretive database of alleged gang members kept by California police officers and the questions of whether law enforcement should need a search warrant to access digital records. This is the kind of story that’s particularly well-suited to a relentless follow-up coverage—the sort of momentum you might see building in the pages of a metro daily after a blockbuster scoop. There are regulatory and legal angles to explore, plus plenty of questions about how the existence of such a database affects individuals and reflects tools used by law enforcement elsewhere.

Reveal published one story about how it’s possible for members of the public to be in the database without even knowing, and another about legislation that would open the database to more public scrutiny. But as of mid-July, it hadn’t published anything in the surveillance and privacy section since April. Many of these stories require enormous resources that few newsrooms have—namely, the time it takes to report them. “There’s this inherent challenge between long-term, long-form, deep investigated work that runs this risk of feeling stale when the pace of news is just so fast,” Díaz says. “We’ve got to figure out a more mid-weight speed for this particular beat because things just move so rapidly in technology.”

The Atlantic, where I’m a staff writer, has tried a similar approach to staying nimble, drilling down on specific beats, inspired in part by the fluid beat structure that Quartz established when it launched in 2012. When I ran the technology section, I asked one of our reporters, Robinson Meyer, to prioritize “police-worn body cameras” as one of his central beats in the months after the fatal police shooting of an unarmed teenager in Ferguson, Missouri. As part of the larger national conversation about the use of such technologies, the topic was timely, complex, and had huge implications for personal privacy and surveillance. Meyer’s focus on what could otherwise be considered a micro-beat produced some fascinating, important stories that were nationally relevant.

An unexpected benefit was, in some cases, that this narrow approach expanded Meyer’s geographic focus. In one memorable story, he found a city in Idaho where police-worn cameras were already the norm. This reporting was instrumental in illuminating the politics around body-worn cameras—including the fact that police officers sometimes support mandates to wear them, a narrative that wasn’t well explored at the time. It also challenged the idea that the technology was new or untested, and helped hone in on the actual accountability problems that body-worn cameras raise. He went on to write about those issues, like whether footage could be edited by officers, how it would be stored and maintained, and, crucially, how the public could access it.

Aaron Harvey, shown here, was wrongly documented in California's secret gang database uncovered by Reveal. The website doesn’t have a technology section per se, but it does cover technology, falling mostly within the realms of privacy and surveillance

Now, as a staff writer, I’m trying something similar in my own work. One of my beats is “self-driving cars,” a designation narrow enough to encourage depth, but broad enough to yield a stream of interesting story ideas. Sure, I may write up the latest Google accident report, but I’m also filing open-records requests to state and federal agencies, visiting test tracks and university labs, interviewing the technologists working on developing special sensors for these vehicles, reading academic work about robot-human interaction, and covering congressional hearings. As this technology advances and becomes more widespread, the need for investigative coverage will become clearer still. The ongoing federal investigation into a fatal crash by the driver of a Tesla using his car’s Autopilot system may be a cultural turning point that will ultimately shape the future of driving. But it’s also a good example of how beat reporters who focus on self-driving cars are (or ought to be) well-prepared to cover the investigation and the broader questions it raises.

These strategies are attempts at avoiding technology coverage that is, in Díaz’s words, “a mile wide and an inch deep.” I’m not just covering Google, the leading company working on this kind of technology and a prominent voice shaping public perception of it, I’m tracking the technology itself and the processes by which it will be integrated into public life.

Sara Watson, a research fellow at the Tow Center for Digital Journalism, says the quality of technology coverage (and criticism, in particular) is improving, but there’s still a long way to go. “Critical angles on technology can live in a lot of different forms: reported pieces, op-eds, blog posts, the business section, satire, science fiction,” she says. “The thing that’s missing on the critical side of the coverage is an attention to what the positive, constructive alternatives could be. That’s the hardest question to answer, and that’s especially hard if you are writing as a journalist. But helping readers imagine alternatives to the things that aren’t quite working for us, or on our behalf, is the way to start holding institutions accountable.”

Signs of progress, Watson says, can be seen in the very makeup of some newsrooms. At BuzzFeed, for example, the tech-focused San Francisco bureau has a reporter on the labor beat. “A position that’s hard to imagine a few years ago, but seems natural given all the surfacing concerns about working in technology and disruption of labor markets,” she says.

In some cases, Watson argues, the critics who do the best work aren’t necessarily reporters, but may be the people with the closest ties to the tech industry. She cites blogger and tech entrepreneur Anil Dash and the programmer Marco Arment as people with “critical voices” who are “closest to the machine so they are well received.” In other words, what they say is more likely to have actual impact.

Being a relative insider in the tech world can be helpful to reporters, too. Mark Gurman, who has covered Apple for the tech-insider site 9to5Mac since he was in high school, and who is known in the industry as a “scoop machine,” just graduated from college and snagged a tech reporting job with Bloomberg. He first cultivated sources at Apple because he was interested in technology—not journalism—and figured out how to go to the “right events” to meet people. Those connections, and his understanding of tech, proved valuable for him as he moved into the blogging world. “Talking to people who work at technology companies, you have to have a certain level of expertise,” he says. “You have to be able to talk the same language.”

He attributes his success breaking news about one of the most secretive companies on the planet to meeting the right people over time and choosing stories carefully. “I was balancing this reporting with college,” he says, “so I really only had time to focus on the bigger stories.” Plus, he adds, choosing his words carefully, “The scoops don’t come from PR people.”

Despite all the excellent tech reporting out there, the signal to noise ratio can make it difficult to suss out the muckraking from the muck.

The obvious difficulty for reporters is, you can’t cover everything. And when you’re covering a handful of beats deeply, there’s even more pressure involved in choosing what to skip. These are the same pressures that face any reporter on any beat, of course. But they are made all the more difficult by newsrooms’ limited and often shrinking resources and by the tech sector’s increasing involvement with the media.

Media companies aren’t just covering tech companies, after all, but partnering with them and, on a deeper level, competing with them

Even for Web-native media ventures, 2016 has been a year marked by losses. Mashable fired several editorial employees as part of a dramatic shift in editorial direction, with plans to emphasize video entertainment over news. Layoffs have also hit the International Business Times, BuzzFeed, Newsweek, and Vice News—though, at Vice, the company characterized the cuts as part of its larger expansion into video.

At the same time, audiences are as fractured as ever, forcing newsrooms to think more deliberately about who they’re serving. Sites like The Information, Pando Daily, Recode, and TechCrunch are widely known in Silicon Valley, but not necessarily influential outside of the tech industry. In the opposite direction there’s The Verge, a once-niche technology site that has expanded beyond gadgets coverage to focus on entertainment, science, and transportation. (Vox Media, which owns The Verge, acquired Recode last year.)

At The Verge, an editorial approach that prizes both breadth and depth seems to be paying off. Its editorial team is reliably quick on news-of-the-day items, but also routinely wows with original feature stories that are just as much about business, culture, health, and criminal justice as they are about technology. One memorable story, in which Colin Lecher details the monopoly on prison phone service, is impressive for both its reporting and its online presentation. It features a ticker that counts how much money you’d have to pay if the time you spent reading the article was time spent making a call from prison.

The Verge also recently launched a new section—a gadget blog it calls Circuit Breaker—that exists primarily as a Facebook page, a move that shows a savvy willingness to experiment in the digital space where many of its readers already spend much of their time. It’s a bold move at a time when Facebook’s success appears to be at odds with the well-being of journalism organizations. Elsewhere, a growing number of news organizations find themselves leaning on billionaires for financial support.

Pierre Omidyar, the eBay founder, has launched two investigative news organizations: First Look Media, in 2013, and before that Honolulu Civil Beat, where I worked for several years as an investigative reporter covering politics. Jeff Bezos, the Amazon founder, bought The Washington Post for $250 million in 2013 and has since leveraged his ownership across tech products, offering limited free access to Washington Post stories on the Kindle Fire app and free six-month digital subscriptions to the Post for Amazon Prime members, for example. He’s also made substantial investments in the newsroom.

The Washington Post has had solid tech coverage since before the Bezos era, including dedicated blogs (and now newsletters) that focus on cultural and policy aspects of technology. But it’s not clear that more resources for the newsroom, or Bezos’s goal to dramatically grow The Washington Post’s national standing, have significantly enhanced the paper’s existing approach to tech. This is an area of particular interest to outsiders who wonder about the extent to which Bezos is involved editorially. The Post has rejected claims that Bezos has tried to sway the Post’s coverage about Amazon, or himself. When the paper published about The New York Times’s investigation into Amazon workplace culture, it was largely sympathetic to Bezos. The headline read: “Is it really that hard to work at Amazon?” To be fair, that story also repeated many of the most devastating details from the Times story. Plus, Erik Wemple, a media critic for The Washington Post, on his blog blasted Amazon’s response to the Times as “weak.” A spokeswoman for the The Washington Post, Shani George, said Bezos’s ownership of the paper “absolutely [does] not” affect its coverage of him or his companies. The paper declined a request for further comment.

BuzzFeed, which has its own robust and serious news effort, has generated controversy for revitalizing sponsored content, an advertising strategy that’s been around for a century but one that is potentially complicated in a world where atomized content travels the social Web alone, unbundled from the website where it originated. Even Facebook, not a proper news organization but a platform that’s now considered crucial to the journalism industry, has faced scrutiny for editorial decisions. Back in May, after Gizmodo reported that former Facebook workers said they routinely suppressed news stories of interest to conservative readers, Mark Zuckerberg, the Facebook founder and CEO, issued a statement promising there was no evidence of this kind of bias. Internal documents, obtained by The Guardian, painted a slightly more nuanced picture: Facebook guidelines instructed editors on how to “inject” stories into Facebook’s “trending topics” section—or “blacklist” topics for removal.

In August, a hoax story falsely claiming that the journalist Megyn Kelly had been fired by Fox News for supporting Hillary Clinton was promoted by Facebook as a trending topic for several hours before being removed. In September, Facebook deleted an article, posted by Norway’s largest newspaper, that featured the iconic Vietnam-era photo of Phan Thị Kim Phúc, frequently referred to as “napalm girl.” Facebook initially defended the decision as consistent with standards that ban users from publishing images of naked children.

Espen Egil Hansen, the editor of Aftenposten, responded with a blistering open letter to Zuckerberg. “First you create rules that don’t distinguish between child pornography and famous war photographs. Then you practice these rules without allowing space for good judgement,” Hansen wrote, calling Zuckerberg the “world’s most powerful editor.” Eventually, Facebook relented. But the episode set off a fresh round of debate over whether Facebook has an ethical obligation to acknowledge the journalistic functions it performs.

During a talk at the Nieman Foundation in September, Jill Abramson, formerly executive editor of The New York Times, called Facebook “the biggest publisher on earth.” Pointing to the furor over its newsfeed and the takedown of the Pulitzer Prize-winning napalm photo, she said, “I don’t think that [Facebook] can maintain this, ‘We’re content neutral,’ stance forever. They have got to step up and take some responsibility.”

All this is happening at a time when journalism’s advertising-based revenue model is shakier than ever, and news organizations have all but lost their grip on distribution. Facebook drives an overwhelming volume of traffic across the Web—up to a quarter of all site visits, according to by the social media management firm Shareaholic last year, and 40 percent of traffic to several top news sites, according to data from the web analytics firm Parse.ly. The platform’s recent decision to emphasize status updates from individuals, as opposed to publishers, in people’s News Feeds generated panic among newsrooms that have already seen traffic from Facebook plummet in recent months.

Companies like Facebook and Google have the power to make or break a newsroom. That’s what makes Facebook, in particular, a daunting “partner-competitor-savior-killer,” as the writer John Herrman put it.

Media companies aren’t just covering tech companies, after all, but partnering with them and, on a deeper level, competing with them. Distribution is only a small, if critical, element of what’s at stake. Facebook and Google, along with a handful of other leading tech companies, are also scooping up a huge portion of overall digital ad revenue—65 percent of it, or $39 billion of the $60 billion spent on Internet ads in 2015, according to Pew’s 2016 State of the News Media report.

Even more devastating to news organizations is Facebook’s dominance in mobile advertising. Last year, at a time when audiences were dramatically shifting away from desktops and toward mobile devices, Facebook already got 77 percent of its total ad revenue from mobile ad sales. News organizations, many of them with majority-mobile audiences, are nowhere near Facebook in terms of overall revenue or mobile share. “There is money being made on the Web,” Pew wrote in its report, “just not by news organizations.”

BuzzFeed, which has its own robust and serious news effort, has generated controversy for revitalizing sponsored content

This likely reflects yet another area where Facebook is trouncing the media: audience engagement. While loyalty to individual news brands is declining—most people who read an article on a cellphone don’t end up reading any other articles on that site in the same month, according to a separate Pew study—engagement with Facebook remains astonishingly high. Globally, Facebook users spend an average of 50 minutes on Facebook, Instagram, and Messenger platforms every day, a stat that’s unimaginable for most media companies. That influence appears to be carrying over to an area where Facebook’s involvement is still relatively new: live video. “CNN is only showing Facebook Live video,” Scott Austin, a technology editor at The Wall Street Journal tweeted the night five police officers were killed in Dallas. “Facebook has become a TV broadcast network virtually overnight.”

By almost every measure, tech companies are, in fact, far more powerful than media companies. Herrman, writing last year for The Awl, argued that the messiness between the two sectors may not resolve itself until there’s a clean split—one in which the press foregoes access, refuses to play by Silicon Valley’s rules, and fully embraces its role as a “marginalized and aggressive” antagonistic force. Then again, he concedes, a Fourth Estate like this might not be able to sustain itself. Others, like Kelly of Wired, take the opposite tack. News organizations distancing themselves from Facebook won’t actually solve the underlying problems the media faces in the mobile-social age.

“The solution has to come out of the same matrix the problem is in,” Kelly says. “I suspect the way we move forward is not relying on big paper investigative spotlight teams, but it will be slightly more decentralized, slightly more ecological, slightly more systematic.”

In the past year or so, several leading tech companies have carved out even more prominent spots for themselves in the news ecosystem. The most recent example is the Facebook live video initiative. Before that, it was Instant Articles, a platform launched with a few high-profile publications last spring. (Instant articles are now open to all publishers.) There have been similar efforts by tech companies to leverage news as a way to keep people’s attention, including projects by Snapchat, Google News, and Apple News.

For news organizations, these partnerships represent the substantial relinquishing of distribution control, at a time when media companies have already lost their influential position as the leading gatekeepers of news and information.

By almost every measure, tech companies are, in fact, far more powerful than media companies

“Should we be regaining control of distribution?” the Tow Center’s Bell asks. “I think it will be regrettable if news organizations didn’t at least have an idea of how that might happen. There is a danger to just say, ‘Okay, this has been dismantled to the point where ad sales, technology, marketing, etcetera, can all be shrunk back to a really small portion of what we do, and we put faith in the idea that Google, Facebook, and whatever comes next will always make the distribution of high-quality journalism a priority.’ But it’s easy to see how those publishing skills may just disappear from publishing.”

That prospect carries frightening implications for any journalist who believes in the importance of autonomous news operations as a foundational value. “Being really distinct from government, from commerce, is what makes journalism journalism and not PR,” Bell argues. “How do you maintain that integrity of separation while at the same time really not being able to exist outside the system?”

Bell says the challenge for news organizations will be to think critically about what it actually means to be a media company in 2016 and beyond. Being a news organization won’t be about selling newspapers, or even just having a website. The New York Times, for example, is selling its own dinner kits—including ingredients for recipes you can find on the NYT Cooking website.

Five or 10 years ago, leading technology-minded journalists and media theorists often talked about the importance of diversifying revenue. Today, that conversation has evolved. Media companies aren’t just tasked with creating more financial streams; they’re being forced to reconsider what they’re actually producing and distributing—and for which of the rapidly multiplying number of platforms.

“Revenue is a proxy for product,” says Bell. “Diversifying revenue doesn’t just mean new ways of making money. It actually means changing completely what you do and being prepared to carry on changing.”