Ronald Hiers, who had been addicted to drugs for nearly five decades, at his Mississippi home in October 2017. A year after a video of Ronald and his wife Carla overdosing went viral, Time and Mic followed up with the couple, who are now clean

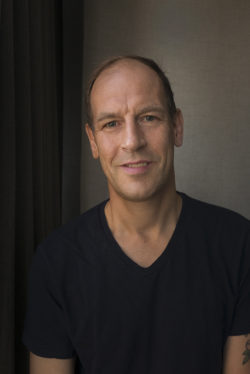

Photographer Graham MacIndoe

Photographer Graham MacIndoe left his native Scotland in 1992 to make it in New York. He worked for outlets such as The New York Times Magazine and The Guardian, taking pictures of Quentin Crisp, Michael Jackson, and other artists, musicians, and writers. He dabbled in drugs, then got addicted to crack cocaine and heroin. He documented his descent into addiction through a series of self-portraits. Arrested for drug possession in 2010, he landed in Rikers Island jail. He enrolled in a drug rehab program while he was being held in an immigration detention center. Today he’s working again as a freelance photographer and teaching photography in New York. He returned to Scotland for a visit in 2017 as the National Portrait Gallery opened “Graham MacIndoe: Coming Clean,” an exhibit of the photographs taken during his addiction. Below are excerpts from a conversation with him about images of addiction and recovery:

Images are forever

From my personal experience, I think that addicts will agree to a lot of things when they’re high that they might not agree to when they’re clean and sober. It’s a difficult thing for somebody in active addiction to give informed consent, not knowing where those pictures are going, especially nowadays. Back in the ’80s, you knew it was going to be a specific newspaper, magazine, or a book, and that was it. Now, because there’s the Internet, multiple platforms, and digital media, everybody can see everything. As a recovering addict, I know that those pictures live forever. When you go for a job, people Google you. If what pops up is a picture of you taking drugs and your name is attached to it, people make instantaneous assumptions about your life and who you are. A common assumption is that addicts don’t recover. I get that all the time.

The functioning addict

There are a lot of functioning addicts. That’s why when Philip Seymour Hoffman died, you’re just like, “Oh, my God.” You hear about it all the time. Not just famous people, but other people. Addiction’s about hiding. When you’re at it, you’re always hiding it. That’s why you don’t see images in that gray area of the functioning addict, as they go toward being the very dysfunctional addict. People don’t want to talk about it because they don’t want people to know, and also because it’s illegal.

Context matters

Depending on how a picture is used and what the context is, it could say a very, very different thing. The very same picture can be used in a gratuitous, voyeuristic sort of way, within a blog, with no context. Or you can put it in the context of this is how a person was, this is the route, and this is where they are now. They found recovery. They can look back at this and say, “Wow.” Pictures of addiction on their own can be misconstrued and misread. Publishing them along with text, interviews, quotes, and data is the most powerful way to talk about addiction and recovery.

The author's husband, photographer Graham MacIndoe, formerly addicted to heroin, documented his descent into addiction through self-portraits. Stellin and MacIndoe co-wrote a memoir about his journey to recovery

Exploiting addiction

Journalists are held to a standard of ethics. Then you’ve got videos on social media, like Instagram, Snapchat, Tumblr, and Facebook. It’s the viral videos that become the bigger thing within the world of media. There’s not a huge amount of people that read The New York Times, compared to those that go on Facebook.

There are people who trawl around neighborhoods and photograph prostitutes or addicts and offer them drugs. Those people are not held to any standard. It can be problematic that the world of media has changed so much over the last 15 years in terms of people being able to take videos on phones and post them instantaneously. As opposed to someone who goes and researches something, spends time, edits it, gets it perfect, and puts it in a magazine or online.

When photographers photograph addicts doing illegal activities, buying drugs, trading drugs, or in buildings where drug deals are going down, they’re putting that addict on the radar of the police. The police are getting clever about how they track these sorts of things. They find out where, and they sometimes raid those houses.

Taking time

There was a couple in Memphis who were both over 50. In the fall of 2016, they had done heroin in a store, walked out on the street, and the heroin was so powerful that they started falling over. People were videotaping them. It went viral. About a year later, Time magazine, in a collaboration with Mic, followed up on the couple, sending a photographer and writer to spend time with them. The people who were in the video are now clean. A short time clean. The article was about how they found recovery. There’s a lot of shaming in images of addiction, but the video that went viral was powerful enough that the couple looked at their lives and said, “Wow. I don’t want to be that person anymore.” That was the impetus for them to go to rehab, get help, and get clean. Even though they were reasonably new in recovery, the pictures and the interviews were compelling and interesting, in the way that they talked about their previous life and what recovery had given to them.

Picturing recovery

Photographs of addiction tend to be about the external, the user, and the environment. It’s the people around you, the darkness, the grimness. Whereas recovery imagery is much more about what you feel inside and what you feel toward the world, those around you, your gratefulness for being in recovery. It’s just like everything else. You’ve got ups and downs, happy times and not happy times. Again, it’s context. How do you say something about recovery that’s real, but also compelling?