The forgotten town of Alto Hospicio (Shelter in the Heights), which lies amid the torrid, windy sand of a relentless Chilean northern desert, tragically came to life last year. From mid-2000 through 2001, every other month, 13- to 16-year-old girls disappeared from the streets. They’d leave home on their way to school one morning and never be seen again.

In frantic despair and begging for help, each of their families, who were low-class, mostly unemployed workers who survived on the leftovers of the nearby port of Iquique, summoned the police and the authorities. But there wasn’t a clue. Combined with the complete failure of police investigations, the message sent by varying authorities was an inconceivable “you better forget about them.” Those girls had probably left by themselves, they’d say, looking for better opportunities elsewhere, or had been convinced by third parties to do so. In both cases, they had surely hit the big cities and had become what everybody expected from them: prostitutes. Case closed.

Further, the police would tell families that their daughters had left, not wanting to stay anymore with them for one of these reasons: alcoholic father beats mother; stepfather rapes stepdaughter; both parents jobless, violent and or depressed; no future in town.

The families organized themselves and kept demanding answers. But nothing happened until last October, when a 13-year-old girl was found bleeding, almost unconscious, walking out of a rubbish dump outside of town. This ninth victim of a psychotic serial killer had survived. She had been kidnapped and raped by a 35-year-old taxi driver who had left her naked, covered with stones, and had told her he would come back the next day to throw her into an old well, where he had buried eight other girls before her. Public opinion was overwhelmed.

Chilean news media, mostly led by men, had followed exactly what the police said about this case. Conversely, feature stories in magazines and TV and newspaper supplements, mostly directed by women, would bring up the story of the town, the way of life of its people, and the issue of unemployment. But, in either case, there was no additional research done on these cases, even though a year before this final kidnapping sociologist Doris Cooper mentioned the possibility of a serial killer. She had urged authorities to look at the pattern—all girls, the same ages, same schools, same town, every other month. But nobody, not even the police, followed her theory. “If I hadn’t been a woman,” she’d say later, “maybe somebody would have listened.” Instead, during these 18 months, most agreed that the girls had run away from dysfunctional parents and left town. There were even sources who dared to say the families had probably sold their daughters for sexual trade.

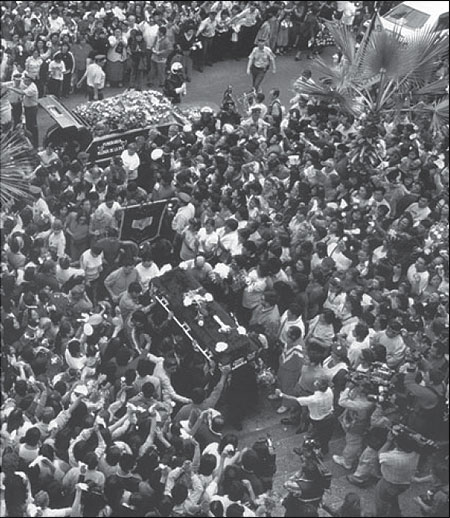

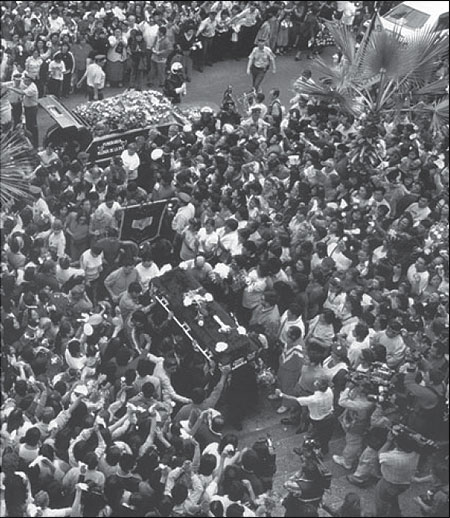

Prejudice overruled attempts to examine other possibilities. After a while, editors would move away from coverage of this story and bring their reporters back. On the burial day of the eight corpses, in the midst of the tears of their mothers, everyone kept silent. The dignity of the families had been swept away. What news coverage showed was the coffins, but we read or heard no apologies.

A massive funeral for eight teenagers raped and killed by a serial killer in Alto Hospicio in northern Chile. Photo courtesy of Paula magazine.

The Role Women Journalists Play

A certain look, a certain feeling about social issues is the value women journalists bring to news coverage in Latin America. Our challenge is in trying our best to report on issues of poverty, discrimination and the tragedies like the one that befell these families in Alto Hospicio and, by doing so, perhaps move the public agenda towards them. Historically, women have shown interest in these topics, but editors and media owners—mostly men—have maintained traditional priorities in news: a reliance on daily headlines, little reporting and research, and a constant focus on politics, economics, sports and entertainment. One problem is that they’ve not realized that public opinion, deep within, has changed its focus. Today, people are not moved by bare facts but are interested in knowing and understanding people’s feelings and reasoning. To put it simply, public opinion is not stuck on the same page as the male editors.

In our countries, the main issue that traditionally has moved public opinion—politics—is fading away and, frankly, it might be for good. Most leaders, when invested with authority, have abused power and/or economic interests. While people die of hunger and neglect in many places throughout the world, money accumulates in the hands of authority. Corruption sets in. People lose hope. Today, the more that sources of information come from formal authority, the farther away the people withdraw.

Media, as a whole, have been slow in understanding this. Women journalists, who have wanted to move the agenda elsewhere but who have had little or no space to do so, have been the exception. We have longed to cover issues that public opinion now seems focused on—human relationships, the workplace, gender issues, discrimination, AIDS, poverty, home violence, raising children, and quality of life. But these issues have had to wait too long, beaten back by stories that lack a sensible point of view, and have resulted in media standardization.

In mid-1999, Uruguayan journalist María Urruzola, a victim of constant sexual harassment from one of her colleagues at work, wrote an article on what was going on at her bureau. She described her treatment in its utmost detail and summoned other women in the country to speak out. She told her male boss that she wanted the piece to be published in her paper, Brecha (The Gap). He agreed. Good for María and good for Brecha. This unlikely outcome gave the newspaper the high credibility it has held ever since.

Women’s impact in reporting and writing is often evident in the “feminine” point of view they bring to analyzing news. Women know about feelings and emotions, and they want to look at the social phenomena hidden behind the facts. And they usually know how to get at stories that other reporters have missed. In fact, recently Latin American women reporters have been bringing many stories to the fore about discrimination, gender, poverty, hunger in Sudan, nine-year-old girls being circumcised in 29 African countries, and what life is like for a Taliban woman under her burka, a story reported long before September 11.

At times, however, they’ve put such issues on the news agenda but the newsroom—with its male editors—has failed to listen. If these issues are not considered part of the “big news” going on, then social issues, per se, seem to be of no interest. Furthermore, they do not sell. But what these editors and media owners miss is that credibility sells by itself.

Last year, Chilean First Lady Luisa Durán de Lagos launched a campaign called “Give a woman her smile back.” She raised funds to pay for dental treatment that would make poor women who had lost teeth not only smile again but feel capable of asking for a job without being ashamed of themselves, act with personality before her husband and children, eat normally, and stand up with dignity. But most of all, Durán asked the media to contribute to this campaign. Of course, it became a 10th priority issue except for women reporters, who did their best to publicize the issue when given extra space or asked to “fill.” Only one broadcast story showed images of the first women who underwent the treatment, talking about the complete change that had taken place in their lives.

Recently, I was in a southern fishing town doing a story on a craftsman who builds marvelous violins from a native Chilean wood called “alerce” (the larch tree). While I talked with his toothless wife, I said to myself: “I won’t write the story until I get her teeth back. I’ll drive everybody nuts, but his violins and her smile are the same thing to me.”

By assuming top positions, women journalists can create the possibility for positive steps forward for others. In Chile, we are getting there. Feature story magazines are edited by women, and many radio broadcasts are run by women. The main TV broadcast news hour has a woman editor. But the other four TV broadcasts do not, and there are no women running newspapers or newsmagazines. Only three women sit on boards of the two big media companies. Even when we feel we are almost there, most of the time our issues are still left out. And what women face when we get to high positions is the challenge of either fighting for a change in the priorities of the news agenda or gradually yielding to our bosses, who in turn yield to political and economic pressures that won’t easily accept anybody changing the order of things.

Women with independent points of view who work inside big media companies and who want to work with their colleagues and bosses to prepare the way for new topics, pluralism and diversity, usually fail. We are either moved to another position or a new boss is placed above us, and our power is diminished. Chile, for example, is the only country that does not have a divorce law. Our media—conservative and reactionary—allows discussion of this in some sections focused on women or family (usually written by women), but the lead “news” article, usually written by men, will always be against.

Women in independent media, however, usually do succeed in their efforts to favor pluralism and diversity and place social issues on the front page. Chilean Internet newspaper El Mostrador, run by a woman editor, has become a hit in breaking news. Its headlines and very good reporting have been considered the standard of several Chilean news media for more than two years now. Yet, the lack of advertisement on the net hurts the paper so it is not clear how long it will survive.

What worries me—and ought to worry others—is that independent media are disappearing everywhere. We either fight for their survival, or we will need to work out a new agenda from inside the core of big media companies. We won’t be alone in this because public opinion badly needs more information on these hidden issues. Following September 11, nothing will be the same. People need and want to know more, to dig in and understand the reasons behind the facts.

Thus, women journalists have a chance now. Editors will turn to us. As women, we know and have experienced discrimination. We understand minorities. We wake up every day intertwining emotions and human relationships, trying to understand others and to work things out from the point of view of those who are affected. And we go to sleep at night thinking about steps we have walked either towards or away from our mission. We have been waiting too long to speak up, for ourselves and for others. We have to take the chance that is now presented to us and go for it.

Veronica Lopez, a 1997 Nieman Fellow, founded and was the editor of several magazines in Chile (Cosas, Caras, El Sábado de El Mercurio, among others) and in Colombia (Semana). She has taught journalism at several universities. She serves on the board of the International Women’s Media Foundation and of Chile 21 Foundation. At present, she is studying the launching of new independent magazines.

In frantic despair and begging for help, each of their families, who were low-class, mostly unemployed workers who survived on the leftovers of the nearby port of Iquique, summoned the police and the authorities. But there wasn’t a clue. Combined with the complete failure of police investigations, the message sent by varying authorities was an inconceivable “you better forget about them.” Those girls had probably left by themselves, they’d say, looking for better opportunities elsewhere, or had been convinced by third parties to do so. In both cases, they had surely hit the big cities and had become what everybody expected from them: prostitutes. Case closed.

Further, the police would tell families that their daughters had left, not wanting to stay anymore with them for one of these reasons: alcoholic father beats mother; stepfather rapes stepdaughter; both parents jobless, violent and or depressed; no future in town.

The families organized themselves and kept demanding answers. But nothing happened until last October, when a 13-year-old girl was found bleeding, almost unconscious, walking out of a rubbish dump outside of town. This ninth victim of a psychotic serial killer had survived. She had been kidnapped and raped by a 35-year-old taxi driver who had left her naked, covered with stones, and had told her he would come back the next day to throw her into an old well, where he had buried eight other girls before her. Public opinion was overwhelmed.

Chilean news media, mostly led by men, had followed exactly what the police said about this case. Conversely, feature stories in magazines and TV and newspaper supplements, mostly directed by women, would bring up the story of the town, the way of life of its people, and the issue of unemployment. But, in either case, there was no additional research done on these cases, even though a year before this final kidnapping sociologist Doris Cooper mentioned the possibility of a serial killer. She had urged authorities to look at the pattern—all girls, the same ages, same schools, same town, every other month. But nobody, not even the police, followed her theory. “If I hadn’t been a woman,” she’d say later, “maybe somebody would have listened.” Instead, during these 18 months, most agreed that the girls had run away from dysfunctional parents and left town. There were even sources who dared to say the families had probably sold their daughters for sexual trade.

Prejudice overruled attempts to examine other possibilities. After a while, editors would move away from coverage of this story and bring their reporters back. On the burial day of the eight corpses, in the midst of the tears of their mothers, everyone kept silent. The dignity of the families had been swept away. What news coverage showed was the coffins, but we read or heard no apologies.

A massive funeral for eight teenagers raped and killed by a serial killer in Alto Hospicio in northern Chile. Photo courtesy of Paula magazine.

The Role Women Journalists Play

A certain look, a certain feeling about social issues is the value women journalists bring to news coverage in Latin America. Our challenge is in trying our best to report on issues of poverty, discrimination and the tragedies like the one that befell these families in Alto Hospicio and, by doing so, perhaps move the public agenda towards them. Historically, women have shown interest in these topics, but editors and media owners—mostly men—have maintained traditional priorities in news: a reliance on daily headlines, little reporting and research, and a constant focus on politics, economics, sports and entertainment. One problem is that they’ve not realized that public opinion, deep within, has changed its focus. Today, people are not moved by bare facts but are interested in knowing and understanding people’s feelings and reasoning. To put it simply, public opinion is not stuck on the same page as the male editors.

In our countries, the main issue that traditionally has moved public opinion—politics—is fading away and, frankly, it might be for good. Most leaders, when invested with authority, have abused power and/or economic interests. While people die of hunger and neglect in many places throughout the world, money accumulates in the hands of authority. Corruption sets in. People lose hope. Today, the more that sources of information come from formal authority, the farther away the people withdraw.

Media, as a whole, have been slow in understanding this. Women journalists, who have wanted to move the agenda elsewhere but who have had little or no space to do so, have been the exception. We have longed to cover issues that public opinion now seems focused on—human relationships, the workplace, gender issues, discrimination, AIDS, poverty, home violence, raising children, and quality of life. But these issues have had to wait too long, beaten back by stories that lack a sensible point of view, and have resulted in media standardization.

In mid-1999, Uruguayan journalist María Urruzola, a victim of constant sexual harassment from one of her colleagues at work, wrote an article on what was going on at her bureau. She described her treatment in its utmost detail and summoned other women in the country to speak out. She told her male boss that she wanted the piece to be published in her paper, Brecha (The Gap). He agreed. Good for María and good for Brecha. This unlikely outcome gave the newspaper the high credibility it has held ever since.

Women’s impact in reporting and writing is often evident in the “feminine” point of view they bring to analyzing news. Women know about feelings and emotions, and they want to look at the social phenomena hidden behind the facts. And they usually know how to get at stories that other reporters have missed. In fact, recently Latin American women reporters have been bringing many stories to the fore about discrimination, gender, poverty, hunger in Sudan, nine-year-old girls being circumcised in 29 African countries, and what life is like for a Taliban woman under her burka, a story reported long before September 11.

At times, however, they’ve put such issues on the news agenda but the newsroom—with its male editors—has failed to listen. If these issues are not considered part of the “big news” going on, then social issues, per se, seem to be of no interest. Furthermore, they do not sell. But what these editors and media owners miss is that credibility sells by itself.

Last year, Chilean First Lady Luisa Durán de Lagos launched a campaign called “Give a woman her smile back.” She raised funds to pay for dental treatment that would make poor women who had lost teeth not only smile again but feel capable of asking for a job without being ashamed of themselves, act with personality before her husband and children, eat normally, and stand up with dignity. But most of all, Durán asked the media to contribute to this campaign. Of course, it became a 10th priority issue except for women reporters, who did their best to publicize the issue when given extra space or asked to “fill.” Only one broadcast story showed images of the first women who underwent the treatment, talking about the complete change that had taken place in their lives.

Recently, I was in a southern fishing town doing a story on a craftsman who builds marvelous violins from a native Chilean wood called “alerce” (the larch tree). While I talked with his toothless wife, I said to myself: “I won’t write the story until I get her teeth back. I’ll drive everybody nuts, but his violins and her smile are the same thing to me.”

By assuming top positions, women journalists can create the possibility for positive steps forward for others. In Chile, we are getting there. Feature story magazines are edited by women, and many radio broadcasts are run by women. The main TV broadcast news hour has a woman editor. But the other four TV broadcasts do not, and there are no women running newspapers or newsmagazines. Only three women sit on boards of the two big media companies. Even when we feel we are almost there, most of the time our issues are still left out. And what women face when we get to high positions is the challenge of either fighting for a change in the priorities of the news agenda or gradually yielding to our bosses, who in turn yield to political and economic pressures that won’t easily accept anybody changing the order of things.

Women with independent points of view who work inside big media companies and who want to work with their colleagues and bosses to prepare the way for new topics, pluralism and diversity, usually fail. We are either moved to another position or a new boss is placed above us, and our power is diminished. Chile, for example, is the only country that does not have a divorce law. Our media—conservative and reactionary—allows discussion of this in some sections focused on women or family (usually written by women), but the lead “news” article, usually written by men, will always be against.

Women in independent media, however, usually do succeed in their efforts to favor pluralism and diversity and place social issues on the front page. Chilean Internet newspaper El Mostrador, run by a woman editor, has become a hit in breaking news. Its headlines and very good reporting have been considered the standard of several Chilean news media for more than two years now. Yet, the lack of advertisement on the net hurts the paper so it is not clear how long it will survive.

What worries me—and ought to worry others—is that independent media are disappearing everywhere. We either fight for their survival, or we will need to work out a new agenda from inside the core of big media companies. We won’t be alone in this because public opinion badly needs more information on these hidden issues. Following September 11, nothing will be the same. People need and want to know more, to dig in and understand the reasons behind the facts.

Thus, women journalists have a chance now. Editors will turn to us. As women, we know and have experienced discrimination. We understand minorities. We wake up every day intertwining emotions and human relationships, trying to understand others and to work things out from the point of view of those who are affected. And we go to sleep at night thinking about steps we have walked either towards or away from our mission. We have been waiting too long to speak up, for ourselves and for others. We have to take the chance that is now presented to us and go for it.

Veronica Lopez, a 1997 Nieman Fellow, founded and was the editor of several magazines in Chile (Cosas, Caras, El Sábado de El Mercurio, among others) and in Colombia (Semana). She has taught journalism at several universities. She serves on the board of the International Women’s Media Foundation and of Chile 21 Foundation. At present, she is studying the launching of new independent magazines.