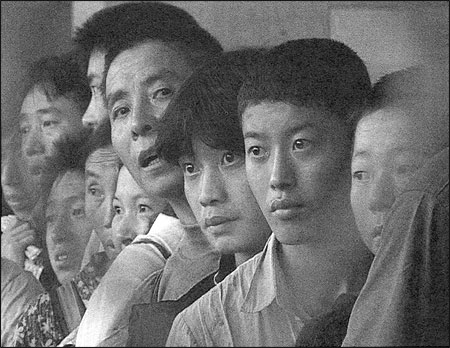

Migrant workers wait for days before being able to get on a train. Photos by Ning Ying, from “Railroad of Hope,” © Eurasia Communications Ltd.

Recent visitors to China, especially to her cities, cannot but notice the breathtaking changes in skylines and infrastructure as well as in social and cultural life since the country embraced the enterprise of “transformation” (zhuanxing) in the early 1990’s. This top-down process entails the overhaul of the socialist planned economy, the systematic shift to the market, and ensuing structural changes in every sphere of Chinese life.

At the same time, a new generation of filmmakers has emerged out of the shadows of the Fifth Generation giants such as Zhang Yimou and Chen Kaige with their epic tales set in rural China and in a distant past. The young filmmakers insistently trained their cameras instead on the changing face of the cities. Their films offer poignant portraits of ordinary people and their environment, irrevocably altered by forces beyond their control. Ning Ying, China’s premiere woman director, is one of them. Her films, fictional or documentary (or combinations of both), stand out because they form a unique, consistently evolving body of work that is infused with a deep social commitment and a penetrating yet playful cinematic vision.

Born in Beijing, Ning Ying studied at Beijing Film Academy and later at Italy’s Centro Sperimentale di Cinematografia. Her training included working as assistant director for Bertolucci’s 1987 film, “The Last Emperor.” Soon after, she embarked on her own directing career in China. To date, Ning Ying has made five feature films (the most recent one is in post-production), and numerous documentaries. On the international level, her best known films include “For Fun” (1992), “On the Beat” (1995), and “I Love Beijing” (2000), known together as the “Beijing Trilogy.” All of them have garnered festival prizes and have been showcased at major art cinema venues worldwide.

Recently this trilogy was shown at the Harvard Film Archive. Together the films record and comment on the tremendous changes in the capital that has undergone a major surgical operation during the 1990’s, in both its physical and moral topography. The trilogy is thus both a historical document of the transformation of the filmmaker’s native city and her cinematic eulogy to a form of life that is rapidly vanishing. When I heard Ning Ying talk about her films, she said, “I first set out to explore Beijing in 1992 with ‘For Fun,’ a comedy about disappearing traditional ways of life. In 1995, with the black-humored ‘On the Beat,’ I focused on the emerging new reality and the difficulty of coping with it. In ‘I Love Beijing,’ the magnitude of changes shaping our lives and the anxieties of the new generation are represented in a rhapsody form, through the eyes of a young, restless taxi driver.”

At the center stage of “For Fun” are Old Han, former gatekeeper of the Beijing Opera Academy, and a group of opera aficionados who form a club to sing, play and quarrel. The film is as much a homage to the old Beijing as a commentary on the tenacity of the bureaucratic mindset, a legacy of the Mao era. “On the Beat” continues Ning Ying’s anatomic vision of the social system in transition, this time through a cinema vérité-style chronicle of the bland or absurd routines of the cops at the Deshengmen Precinct, which include chasing a rabid dog and arresting a migrant artist peddling seminude calendar posters. “I Love Beijing,” last in the trilogy, shows a Beijing whose pace and scale of change could now only be frantically captured through the window and reflection mirror of one of the thousands of taxis on Beijing’s highways. Following the cabbie Dezi, we are taken on a voyage across Beijing. He is always on the move, people and places flow quickly in and out of his life. Dezi’s restless search for love and stability amidst chaos and flux mirrors Beijing’s own ambitious yet confused search for identity between a disappearing world and an unknown future.

The triptych of the city registers the emergence of new urban identities and globalized lifestyles as China marches into the market and the world at large. But they also reveal the human cost of such “surgical operations” and the disintegration of the social and moral fabric of the city and the nation.

Ning Ying’s sociological and anthropological interests and approaches evidenced in the trilogy—such as using nonprofessional actors and extensive location shooting—are more directly expressed in her documentary work beyond Beijing and urban life. In several short programs, commissioned by UNICEF, her films depict urgent social issues and uneven development in China, such as HIV/AIDS, women’s trafficking, and street children.

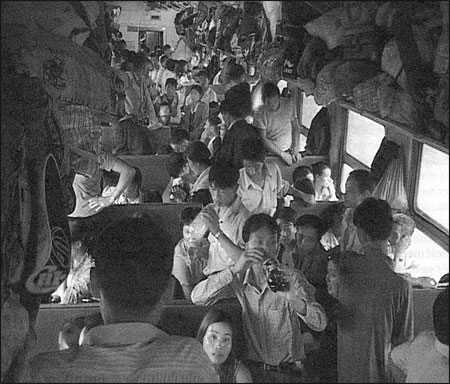

In 2001, Ning Ying made a feature-length documentary, “Railroad of Hope,” a searing portrait of internal mass migration in China. Following hundreds of agricultural workers from Sichuang Province to Xinjiang, China’s northwest frontier, a journey of more than 3,000 km, Ning Ying spent three days and nights in the crowded train befriending and interviewing these hopeful peasants with their many dreams for the future, some shared and some diverging. Most of them, especially the young women, are on their first trip away from their native villages as well as their first time on a train. “Railroad of Hope” was awarded the Grand Prix du Cinema du Reel in Paris in 2002. The award citation calls the film “outstanding for the power of its images, its full and deeply penetrating vision …. A film that sweeps us up into stories and energy of life, over and beyond the simple duration of this journey toward hope. …”

Zhang Zhen teaches cinema studies at New York University. Information about Ning Ying’s films can be found through her Beijing-based company at eurasia@public3.bta.net.cn.

When interviewed during filming, one woman said, “I don’t know even what it means, the word ‘happiness.’ People are happy when they can stay at their home.”

Passengers are excited to have arrived in Xinjiang after traveling for three days.

All photos by Ning Ying, from “Railroad of Hope,” © Eurasia Communications Ltd.