Should a single mistake define you for the rest of your life?

That’s the central question behind “Fresh Start,” a new initiative at The Boston Globe where we allow people named in older stories to appeal their presence in our pages.

At first glance, the effort may sound antithetical for a daily newspaper. After all, publications like ours have a long history of fighting to make information public, and of publishing information that some might prefer to stay hidden.

But times change, and as journalists, we must change with them.

In the past, a Globe story about a minor crime or embarrassing incident would often be relegated to “back-of-the-section” placement in the newspaper. Because of the daily nature of print, the story would be read by some and then quickly forgotten when the next day’s edition arrived. This wouldn’t mean the entire case would be wiped from the public record: You could still find the story by searching archives at the library, or from other archival sources. But the story — and those featured in it — would not remain easily discoverable for years to come.

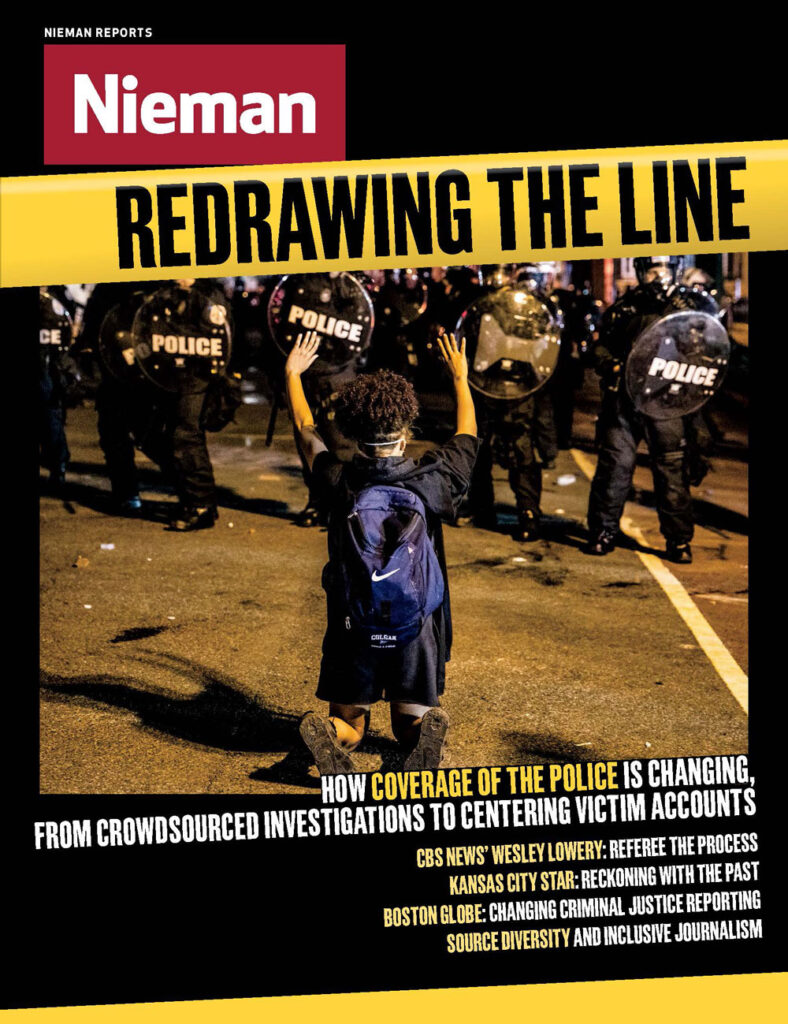

Related Reading

To Change Its Future, The Kansas City Star Examined Its Racist Past

By Mará Rose Williams

To Move Forward on Racial Equity, Newsrooms Need to Reckon with Their Pasts

By Sewell Chan

That’s no longer the case. The runaway power of search engines and other technologies puts a vast amount of information at the fingertips of anyone with a functional Internet connection. For some private citizens, that means one minor event in their past documented by The Boston Globe could appear at the top of a search result of their name. Forever. The global behemoths behind these technologies offer no recourse to someone affected by their platforms; often, one can’t even find contact information on their websites to log a complaint.

Furthermore, the decision to cover a minor crime or incident has always been inherently unequal and random. Anyone who has ever worked a cop beat knows that the severity of the crimes you cover depends, in part, on what else happens that night. The Globe, like every other metro publication in the country, does not have the bandwidth to follow every single crime in our region to conclusion as they wend through various legal systems. And, as the uprising that followed George Floyd’s murder made clear, our nation has a long history of applying law enforcement unequally to communities of color, an injustice that has no doubt been reflected in our coverage of local policing over the years.

Through no intent of our own, many minor stories on our websites, some years old, now immortalize the worst decisions and moments in regular people’s lives. We’ve heard from subjects over the years who tell us that one story, camped at the top of a search result for their name, has become a barrier for employment, relationships, and educational opportunities. This was never the goal of our journalism, to apply a permanent stain haphazardly and unequally to an individual for the rest of time.

Enter Fresh Start. A 10-person committee of journalists spent months defining the scope of the initiative, speaking with community leaders and criminal justice experts to help formulate processes and procedures for how to consider cases from people affected by these stories. We also reached out to other newsrooms who’d crafted similar programs, including Cleveland.com, which has been an early leader in this area.

Here’s how it works: A person who is mentioned in a prior story can fill out a form on our website to request that we take a look at their case. The applicant provides the link to the story, any relevant documents, a few identifying characteristics, and an explanation as to why this story is causing them harm.

Requests must come directly from individuals. Lawyers cannot file a case on behalf of a client; we don’t want to give someone privileged enough to hire legal representation an edge. And we won’t accept claims from corporations or government agencies. This program is meant to help individuals, not to clear away information that holds powerful organizations accountable for their actions. We also maintain a higher standard of consideration for people in positions of public trust, such as politicians, police officers, or teachers.

Our committee reviews every case individually, weighing a number of factors: Were charges dismissed? Was there a conviction? How severe was the crime? Was this an isolated incident, or part of a larger pattern? One of the most important questions we seek to answer is: Does the news value of the story currently outweigh the harm being done to an individual?

While we review every case, we act only on some. For those cases we deem to have merit, we have a number of options for resolution, which include: Adding an editor’s note or an update to a story; removing the article from search engine results; and anonymizing an individual mentioned in the story. In extreme cases, we may consider removing a story entirely from our website. All decisions are ultimately made by the Globe at its own editorial discretion.

Our process, while well-considered, will necessarily evolve. We don't pretend to have all the answers, so we plan to solicit feedback from the community and keep open minds in the early stages of this initiative.

The program has been lauded by some, particularly from the field of criminal justice reform. We’ve also heard from traditionalists who feel uneasy about the precedent we’re setting for news publications.

We understand that unease. We’re not in the business of rewriting the past. But we can’t dogmatically hold on to outdated practices and standards, either, in the face of changing circumstances.

With Fresh Start, we’re taking a bold step to ensure our coverage of someone's past doesn't unfairly hinder their ability to shape their future.

Jason Tuohey is The Boston Globe's managing editor for digital.