Copley News Service, my professional home for 30 years, sadly has become the poster child for the fate of regional news bureaus in Washington in the 21st century, having soared to the highest peaks of our profession only to crash ignominiously less than two years later. It was our D.C. bureau that uncovered the worst Congressional corruption ever documented that sent a war hero congressman to prison—reporting that garnered a Pulitzer Prize for the bureau and The San Diego Union-Tribune, then a Copley paper—only to be shut down as a victim of the profession’s new economic realities.

Those realities mean that today only the biggest news organizations can maintain anything resembling a Washington, D.C. bureau. The victims in recent years all carried respected and established names in journalism—Copley, Cox, Newhouse, Media General. Others, like Gannett, Hearst, Scripps and The Des Moines Register survive, with good reporters fighting the good fight to keep alive bureaus that are mere shadows of what they once were.

See "A Changing of the Guard in Washington, D.C. News Bureaus" about the San Diego- based Watchdog Institute’s recent hiring of a full-time Washington, D.C. correspondent »But the real victims are the citizens of major cities like San Diego, who after they lost Copley have had no reporters in D.C. watching out for them—journalists who know which issues they care about and will ask tough questions for them. This is why when I think about the closing of the Copley bureau, my first thought is not of the Pulitzer Prize and the corruption of Randy “Duke” Cunningham, but of cut flowers and the border with Mexico, steel dumping and museum earmarks, and Osprey testing and closures of Veterans Administration (VA) hospitals.

Too many editors think all that is missed when a Washington bureau shuts down is the absence of somebody to watch local members of Congress, tabulate their votes, and make sure they explain their actions. But regional bureaus do much more than that. These are stories that might not even make the front page and almost certainly aren’t going to win journalism awards. But the little-noticed routine coverage that regional bureaus provide is what has stayed in my mind, and this means that I think of roses and carnations and chrysanthemums—cut flowers.

Following the Flowers

Regional reporters on the federal government beat find themselves becoming experts on strange topics. I became an expert on cut flowers because San Diego County is the cut flower capital of the United States. In fact, the city of Encinitas in northern San Diego County calls itself the “flower capital” and boasts of introducing the poinsettia to this country.

For the almost 60,000 residents of Encinitas, we were their watchdog reporters in Washington. So when President George H.W. Bush went to Cartagena, Colombia on February 15, 1990, I went with him. (During my tenure in D.C., I traveled with presidents to 88 countries.) But I did not write only about the drug summit that drew Bush to Colombia. Rather, I covered my beat—which meant the issues of concern to residents of Southern California. Unlike my colleagues—and to the amusement of several of them—I wrote stories about the president’s talks with his Colombian counterpart about the trade ramifications of Colombia’s effort to seize a big part of the American cut flower market.

It’s probably safe to say I am the only reporter on that trip who wrote as much about cut flowers as I did about the drug summit. I admit that I did not expect to find it fulfilling to research this trade dispute, but doing so was a reminder of how the element of surprise is one benefit of working this beat. It turned out to be a fascinating story—in part because, in its particulars, it wove its way into familiar political zones.

The shorthand version is that American growers were a little slow in adapting to the marketplace. In the 1980’s, they saw little reason to sell flowers in grocery stores. This provided an opening to growers in Colombia and Ecuador and they seized it. And before domestic growers knew what had happened, a big chunk of the marketplace was gone.

So what did the U.S. growers do, having misread the market? Demand protection from the government. So on this presidential trip, flowers became a point of discussion between two presidents with a real-life impact on hundreds of acres in San Diego County and thousands of jobs, as Bush pushed policies to get Colombians to switch from drug production to flower growing despite the hardship this would impose on American growers.

No national publication was writing this story. Ever since technology made it feasible for newspapers across the country to open bureaus in Washington, though, it is exactly the kind of story that these regional beat reporters have specialized in. And such stories are still being done; it’s just that there are fewer of them.

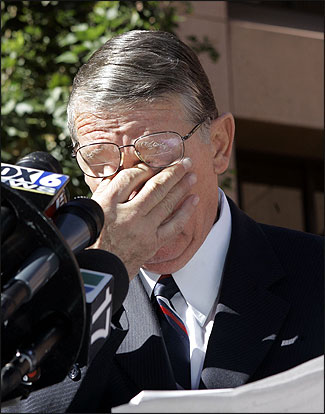

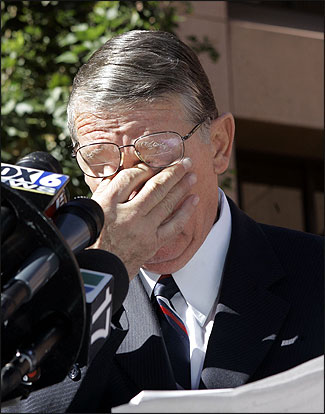

Republican Congressman Randy “Duke” Cunningham spoke about his resignation in 2005 after pleading guilty to bribery charges revealed by reporters from Copley News Service. Photo by Lenny Ignelzi/The Associated Press.

Diminishing Coverage

The Des Moines Register still watches the Department of Agriculture, but with only one reporter. Gone is the larger bureau that won Pulitzers for its coverage of the intersection of government and farming. Gone, too, is intensive coverage of NASA by Media General and the larger Houston Chronicle bureau or the old Houston Post bureau. Gone as well is the exhaustive coverage of border and immigration issues by Copley. Marcus Stern is best remembered for breaking the Cunningham story, but he would tell you he is proudest of the stories he broke on the border. In early 1995, Stern was a lonely voice challenging the Clinton administration’s claims of great success in Operation Gatekeeper, its crackdown on illegal immigrants crossing at the San Diego sector of the border. “The administration launched a PR campaign to convince the public that the crackdown was working,” recalled Stern recently. “We were the only ones that didn’t bite and we were right.”

Andrew Alexander has similar memories of the regional coverage he oversaw as chief of the Cox bureau. He did what all bureau chiefs of regional papers did—made frequent trips to the newspapers and returned with a long list of Washington stories they could not report on their own. “We frequently dug into the Washington bureaucracy to report on problems or plans involving local issues and projects,” he said. “We did this often with stories about plans to close or cut VA centers in some of our circulation areas. Or we uncovered political roadblocks to highway funding projects. Whenever people from our local areas testified before Congress, we were there. In many cases, these were local officials from smaller Cox communities. That’s a pretty big story for a local paper.”

Business coverage—like the cut flower story—often gets overlooked as an important service of regional bureaus. Alexander remembers stories Cox reporters did about government investigations or inquiries involving big Atlanta employers like Coca-Cola, Delta Air Lines, or the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Cox specialized in air industry issues involving routes, mergers and investigations of Delta—critical stories in Atlanta with one of the world’s busiest airports.

Deeper Digging

As beat writers know, it’s in doing these routine stories that they sniff out situations worthy of deeper digging. Stern only got the Congressional corruption story because he knew Cunningham well and because the Copley bureau was working on a routine story about the congressman. Like the other regional bureaus, we were following up on a study of privately funded Congressional travel released by Northwestern University’s Medill News Service, the Center for Public Integrity, and American Public Media. Cunningham was by no means the biggest traveler. He had taken only six trips. But two of the trips intrigued Stern. Both were to Saudi Arabia, a country the congressman had previously shown little interest in, and both were paid for by a Saudi native who lived in his district.

In another reporter’s story, Cunningham said the trips were “to promote discourse and better relations between the two nations.” Because Stern knew Cunningham so well—and knew his attitude toward Arab nations—his reaction was: “I don’t believe it.”

Stern launched an exhaustive search of records to try to find the real reason for the trips. He looked at everything about the man who paid for the trips, everything that could shed light on connections between Cunningham and Saudi Arabia. He found nothing.

Finally, in frustration, he launched what he called a “lifestyle audit” of Cunningham. That meant checking all available databases to see whether the congressman was showing any upgrades in his lifestyle. It was during that “audit” that he uncovered the purchase of Cunningham’s house for a wildly inflated price by a Washington-based defense contractor. It was the first—but certainly not the last—bribe we found.

He won a Pulitzer for that story along with his primary reporting partner Jerry Kammer, who broadened the coverage with a groundbreaking look at how the earmark system worked as demonstrated by the role of lobbyist and former San Diego Representative Bill Lowery. But even on the day we stood on the stage at Columbia University accepting that award, Stern told me only half in jest that his effort had been a failure. After all, he said, he never did nail down just why Cunningham took those two trips to Saudi Arabia.

That is the kind of success—and failure—that keeps this kind of beat reporting at these regional bureaus going. A hardy few still look at agencies and track votes and do lifestyle audits. There just aren’t enough of them, and the ones still there are stretched very thin. So place some flowers—cut ones, please—on the grave of the old, big regional bureau—the ones that carved out these vital beats and served constituents well.

George E. Condon, Jr. joined CongressDaily and National Journal as a White House correspondent when Copley News Service closed its Washington, D.C. bureau in 2008.

Those realities mean that today only the biggest news organizations can maintain anything resembling a Washington, D.C. bureau. The victims in recent years all carried respected and established names in journalism—Copley, Cox, Newhouse, Media General. Others, like Gannett, Hearst, Scripps and The Des Moines Register survive, with good reporters fighting the good fight to keep alive bureaus that are mere shadows of what they once were.

See "A Changing of the Guard in Washington, D.C. News Bureaus" about the San Diego- based Watchdog Institute’s recent hiring of a full-time Washington, D.C. correspondent »But the real victims are the citizens of major cities like San Diego, who after they lost Copley have had no reporters in D.C. watching out for them—journalists who know which issues they care about and will ask tough questions for them. This is why when I think about the closing of the Copley bureau, my first thought is not of the Pulitzer Prize and the corruption of Randy “Duke” Cunningham, but of cut flowers and the border with Mexico, steel dumping and museum earmarks, and Osprey testing and closures of Veterans Administration (VA) hospitals.

Too many editors think all that is missed when a Washington bureau shuts down is the absence of somebody to watch local members of Congress, tabulate their votes, and make sure they explain their actions. But regional bureaus do much more than that. These are stories that might not even make the front page and almost certainly aren’t going to win journalism awards. But the little-noticed routine coverage that regional bureaus provide is what has stayed in my mind, and this means that I think of roses and carnations and chrysanthemums—cut flowers.

Following the Flowers

Regional reporters on the federal government beat find themselves becoming experts on strange topics. I became an expert on cut flowers because San Diego County is the cut flower capital of the United States. In fact, the city of Encinitas in northern San Diego County calls itself the “flower capital” and boasts of introducing the poinsettia to this country.

For the almost 60,000 residents of Encinitas, we were their watchdog reporters in Washington. So when President George H.W. Bush went to Cartagena, Colombia on February 15, 1990, I went with him. (During my tenure in D.C., I traveled with presidents to 88 countries.) But I did not write only about the drug summit that drew Bush to Colombia. Rather, I covered my beat—which meant the issues of concern to residents of Southern California. Unlike my colleagues—and to the amusement of several of them—I wrote stories about the president’s talks with his Colombian counterpart about the trade ramifications of Colombia’s effort to seize a big part of the American cut flower market.

It’s probably safe to say I am the only reporter on that trip who wrote as much about cut flowers as I did about the drug summit. I admit that I did not expect to find it fulfilling to research this trade dispute, but doing so was a reminder of how the element of surprise is one benefit of working this beat. It turned out to be a fascinating story—in part because, in its particulars, it wove its way into familiar political zones.

The shorthand version is that American growers were a little slow in adapting to the marketplace. In the 1980’s, they saw little reason to sell flowers in grocery stores. This provided an opening to growers in Colombia and Ecuador and they seized it. And before domestic growers knew what had happened, a big chunk of the marketplace was gone.

So what did the U.S. growers do, having misread the market? Demand protection from the government. So on this presidential trip, flowers became a point of discussion between two presidents with a real-life impact on hundreds of acres in San Diego County and thousands of jobs, as Bush pushed policies to get Colombians to switch from drug production to flower growing despite the hardship this would impose on American growers.

No national publication was writing this story. Ever since technology made it feasible for newspapers across the country to open bureaus in Washington, though, it is exactly the kind of story that these regional beat reporters have specialized in. And such stories are still being done; it’s just that there are fewer of them.

Republican Congressman Randy “Duke” Cunningham spoke about his resignation in 2005 after pleading guilty to bribery charges revealed by reporters from Copley News Service. Photo by Lenny Ignelzi/The Associated Press.

Diminishing Coverage

The Des Moines Register still watches the Department of Agriculture, but with only one reporter. Gone is the larger bureau that won Pulitzers for its coverage of the intersection of government and farming. Gone, too, is intensive coverage of NASA by Media General and the larger Houston Chronicle bureau or the old Houston Post bureau. Gone as well is the exhaustive coverage of border and immigration issues by Copley. Marcus Stern is best remembered for breaking the Cunningham story, but he would tell you he is proudest of the stories he broke on the border. In early 1995, Stern was a lonely voice challenging the Clinton administration’s claims of great success in Operation Gatekeeper, its crackdown on illegal immigrants crossing at the San Diego sector of the border. “The administration launched a PR campaign to convince the public that the crackdown was working,” recalled Stern recently. “We were the only ones that didn’t bite and we were right.”

Andrew Alexander has similar memories of the regional coverage he oversaw as chief of the Cox bureau. He did what all bureau chiefs of regional papers did—made frequent trips to the newspapers and returned with a long list of Washington stories they could not report on their own. “We frequently dug into the Washington bureaucracy to report on problems or plans involving local issues and projects,” he said. “We did this often with stories about plans to close or cut VA centers in some of our circulation areas. Or we uncovered political roadblocks to highway funding projects. Whenever people from our local areas testified before Congress, we were there. In many cases, these were local officials from smaller Cox communities. That’s a pretty big story for a local paper.”

Business coverage—like the cut flower story—often gets overlooked as an important service of regional bureaus. Alexander remembers stories Cox reporters did about government investigations or inquiries involving big Atlanta employers like Coca-Cola, Delta Air Lines, or the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Cox specialized in air industry issues involving routes, mergers and investigations of Delta—critical stories in Atlanta with one of the world’s busiest airports.

Deeper Digging

As beat writers know, it’s in doing these routine stories that they sniff out situations worthy of deeper digging. Stern only got the Congressional corruption story because he knew Cunningham well and because the Copley bureau was working on a routine story about the congressman. Like the other regional bureaus, we were following up on a study of privately funded Congressional travel released by Northwestern University’s Medill News Service, the Center for Public Integrity, and American Public Media. Cunningham was by no means the biggest traveler. He had taken only six trips. But two of the trips intrigued Stern. Both were to Saudi Arabia, a country the congressman had previously shown little interest in, and both were paid for by a Saudi native who lived in his district.

In another reporter’s story, Cunningham said the trips were “to promote discourse and better relations between the two nations.” Because Stern knew Cunningham so well—and knew his attitude toward Arab nations—his reaction was: “I don’t believe it.”

Stern launched an exhaustive search of records to try to find the real reason for the trips. He looked at everything about the man who paid for the trips, everything that could shed light on connections between Cunningham and Saudi Arabia. He found nothing.

Finally, in frustration, he launched what he called a “lifestyle audit” of Cunningham. That meant checking all available databases to see whether the congressman was showing any upgrades in his lifestyle. It was during that “audit” that he uncovered the purchase of Cunningham’s house for a wildly inflated price by a Washington-based defense contractor. It was the first—but certainly not the last—bribe we found.

He won a Pulitzer for that story along with his primary reporting partner Jerry Kammer, who broadened the coverage with a groundbreaking look at how the earmark system worked as demonstrated by the role of lobbyist and former San Diego Representative Bill Lowery. But even on the day we stood on the stage at Columbia University accepting that award, Stern told me only half in jest that his effort had been a failure. After all, he said, he never did nail down just why Cunningham took those two trips to Saudi Arabia.

That is the kind of success—and failure—that keeps this kind of beat reporting at these regional bureaus going. A hardy few still look at agencies and track votes and do lifestyle audits. There just aren’t enough of them, and the ones still there are stretched very thin. So place some flowers—cut ones, please—on the grave of the old, big regional bureau—the ones that carved out these vital beats and served constituents well.

George E. Condon, Jr. joined CongressDaily and National Journal as a White House correspondent when Copley News Service closed its Washington, D.C. bureau in 2008.