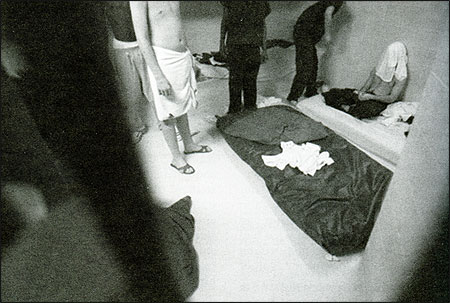

Six inmates hang out in a cell designed for four in North Little Rock’s Observation and Assessment Center. Two youths are forced to sleep on the floor a few feet from the communal commode. Photo by Stephen B. Thornton/The Arkansas Democrat-Gazette.

“Did the dorm manager ever hit you or threaten you?”

“Yes. He threatened me. He was talking about if I ever tell them [staff] what they can’t do—then I’m gonna have to deal with him. And if I have to deal with him, then something bad’s gonna happen.”

—Sixteen-year-old boy in Arkansas’ serious offender program.

What does happen to children who commit serious crimes and are sent to state-run juvenile facilities instead of adult prisons?

That was a question I posed in April 1997 after a 14-year-old boy shot another teenager to death on a school bus. The shooter was transferred to adult court. He was convicted of first-degree murder and sentenced to 46 years in prison.

So how would that same boy have been treated in the juvenile system? How does the state deal with child murderers, rapists and chronic delinquents? Could they be reformed? Are they being rehabilitated?

The answer would shock Arkansans who were generally unsympathetic to young murderers in the wake of the March 24, 1998 shooting deaths of four students and a teacher at Westside Middle School near Jonesboro by 13-year-old Mitchell Johnson and 11-yea-rold Andrew Golden.

Our six-part series published in June 1998 revealed physical, sexual and emotional abuse of children 11 to 17 years old by untrained workers, some of whom had criminal records. Boys were hog-tied; forced to sleep outside on the ground in freezing weather; slugged in the face and denied medical attention despite gaping, bloody wounds; stripped of their clothes and placed in cells after the air conditioning was turned down, and threatened with death if they reported the abuse.

The first stopping point in the system, the Observation and Assessment Center [O&A] in North Little Rock, was a former jail built for 84 inmates. It often housed more than 140 children. Six boys were assigned to a windowless cell built for three. The toilets regularly overflowed raw sewage which the kids were forced to clean up. The three “extra” boys in the cell slept on that same floor on thin blue mattresses, inches away from the toilet.

The handling of juveniles held in detention is an issue that can be reported in every state, despite the confidentiality hurdles. It is an overlooked but important story at a time when the public wonders why juvenile offenders aren’t reformed and some go on to commit horrible crimes as adults.

Being able to find and verify information was the key to reporting our story. The state Freedom of Information Act [FOI] also became a critical tool for us—but only after some employees risked their jobs to supply me with names and documents. Arkansas law prohibits releasing the name of a juvenile in state custody. The employees are even better protected. Once fired, a worker’s name and the reason are not released until he has exhausted his appeals, which can take two years. One file outlining numerous abuse incidents at O&A was renamed as a personnel file to keep it from being released under the FOI.

After months of repeatedly interviewing employees and being escorted through the various institutions, I began to get calls from personnel alerting me to abuse incidents. When the abuses had not been reported to anyone but me, I alerted Arkansas’ Department of Human Services. In turn, DHS gave me some access to incident reports and investigators, checking out the allegations I had passed along. Former employees also supplied me with year-old incidents that should have been investigated but often hadn’t been. In fact, many abuse reports had been destroyed. I received tips about alleged abuse by community providers who worked with the boys after they were released. During the six months we were reporting this story, a DHS memo complained that the staff was not reporting all abuse incidents to the main office, and the administration didn’t “want to learn of it from the press (especially Mary Hargrove).”

Once I had the names of children allegedly abused and the staffer involved, I filed FOI’s on follow-up investigations by the state police and the DHS investigative unit. This allowed me to review the quality, or mishandling, of state investigations and get outside independent verification of the abuses.

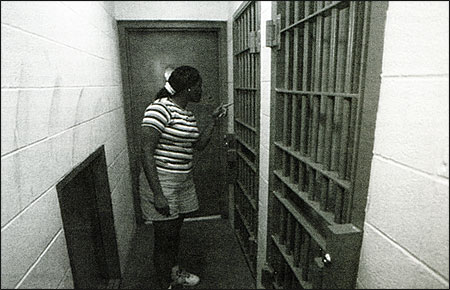

Our photo editor allowed photographer Stephen Thornton to go with me to the facilities at all hours. We made an agreement with DHS to mask the kids’ faces. The pictures were critical to the success of the series. These kids needed to be seen as teenagers, not abstract monsters who should be hidden away and forgotten. The pictures also documented the stark reality of their living conditions in a manner words could not fully convey. I insisted we use two photo pages to display them.

In my 25 years career as a newspaper journalist, I have written more than 40 series, but this project took some unprecedented ethical and journalistic twists before it was published. In April 1998 I met with DHS Director Lee Frazier for four hours, outlining the abuses I’d uncovered. His response: “I don’t believe you.” That same night, a mother who said her son had been beaten and raped a few days earlier at the O&A Center telephoned me. A woman employee, angry because the boy had called her “a bitch,” had placed him in a cell with four older boys and ignored his tearful cries to be let out. Three of the four boys later admitted to tormenting the boy whom I called Chris. Two of them said the fourth boy had attempted to force Chris to have oral sex.

Chris was not taken to a doctor for two days and was not allowed to call his parents or his lawyer, although he repeatedly asked to do so. Soon after that, a group of boys rioted at O&A and demanded to be taken to the city jail. One boy was attacked by guards at another state facility in nearby Alexander. He needed five staples to close the wound in his head. None of this was being reported by the media. In fact, few people were aware of O&A’s very existence.

The abuses I was uncovering were so bad that I became concerned that I could not write the series fast enough to prevent more children from being hurt. I have a heart condition, and there were days when I could not work or could only work for a few hours. After talking with Executive Editor Griffin Smith Jr. and Managing Editor Bob Lutgen, I briefed DHS Chief Counsel Jonann Coniglio and asked her to take some action to protect the boys while I was writing.

Coniglio toured O&A with me and checked into the new allegations of abuse I had detailed. Alarmed, she called Governor Mike Huckabee’s legal counsel. The governor, in what staff memos termed a “preemptive strike” to head off bad publicity, held a press conference April 24 announcing I had uncovered serious incidents of abuse. He did not provide details, but he did vow to correct the problems immediately.

Reporters descended on DHS trying to scoop me. They could do little without names. The pressure was on to print right away. My editors supported me when I insisted we wait for the completed series and not be panicked into breaking stories out. I feared that would dilute the impact. Any single abuse story could be explained away as an isolated, but unfortunate, incident. But a series detailing dozens of vicious incidents, often by the same employees, left no doubt that these problems had been covered up for years, that the abuse was rampant, and that the system needed a drastic overhaul.

The writing also had to be carefully thought out. I was well aware that some of the boys were dangerous and difficult to deal with. I took pains to highlight the courage of teachers and staff who were helping them, even though they had been physically attacked by these boys. Yet I saw many of these kids as troubled teens who were vulnerable and might have been helped if the state had an adequate system. That was important to portray because our readers, outraged by juvenile crimes, were predisposed not to care about this population. But in many cases, these boys who were being abused weren’t in the system because of dangerous crimes they’d committed.

For example, the boy I called Chris had been declared delinquent for stealing two packs of cigarettes. He didn’t belong in a serious offender program. Another boy, David G., was emotionally disturbed and difficult to be around. He needed psychiatric care. He, too, was placed in a cell with older boys who were there because of violent acts they’d committed. The employees who put him in there suggested, “Beat him up and do him good. Don’t leave any marks.” One worker threatened to kill the boys if they crossed him. He warned them he could come into their rooms at night while they slept, strangle them, dump their bodies in the pond behind the facility, then claim they died trying to escape. And no one would care enough to ask questions.

Because of the length and the graphic nature of the stories, we decided to publish only on Sundays and Mondays for three weeks. We ran an overview box on the series indicating the content of the stories to come. It was a gamble. We wondered if readers would lose interest. Fortunately, our first two stories generated strong reaction follow-up stories each day. And on Friday of our first week, the governor announced that O&A would be closed within 60 days.

As our series ended, DHS Director Frazier resigned, citing pressure from the series. The Legislature has held hearings based on our series, and several lawmakers are drafting bills to correct problems we identified.

While conditions are improving at the facilities, calls still come in alerting us to incidents. The state’s only lock-down facility for juveniles in its custody is the Alexander Youth Services Center, located about 15 miles from Little Rock. When O&A was closed, all the boys were transferred there. We have since reported a variety of related stories including the escape of a 17- year-old boy from the Alexander Center, a staff member at Alexander who was stabbed in the face five times by a 15-year-old with a history of violence, and a Texas man who innocently wandered onto the Alexander campus and actually got into the unit where the Jonesboro boys are kept, despite extra security.

All of these are stories our readers would not have been aware of in the past.

Youth Service Worker Debra Rouse yells into an isolation cell for quiet after lights out at North Little Rock’s Observation and Assessment Facility. Photo by Stephen B. Thornton/The Arkansas Democrat-Gazette.

Mary Hargrove has been Associate Editor for The Arkansas Democrat- Gazette for four years. She was Managing Editor/Projects for The Tulsa Tribune, where she worked for 18 years before it closed in 1992. She is past-President and Chairman of Investigative Reporters & Editors, a nonprofit educational organization which has 4,000 print and broadcast members. This series (referred to in this article) by Hargrove and reporters Patrick Henry and Linda Satter, tied for first place with The Washington Post in the Daily Newspapers over 100,000 Circulation category of the 1998 Casey Medals for Meritorious Journalism. This award recognizes distinguished coverage of disadvantaged and at-risk children and their families.