If our focus on social media is primarily about how to use them as “tools” for journalism, we risk getting it backward. Social media are not so much mere tools as they are the ocean we’re going to be swimming in—at least until the next chapter of the digital revolution comes along. What needs our attention is how we’re going to play roles that bring journalistic values into this vast social media territory.

It is essential to begin by understanding various social media sites and the ways they can enhance the work journalists do. A regular perusal of sites like 10000words.net and savethemedia.com is a great way to do this. But how do we move beyond acquainting ourselves with this world and actually figure out how to “use” it for journalism, which requires understanding its nature and impact on participants and on public life?

What does it mean to journalists, for example, that people are in large measure obtaining, and shaping, their information so differently than they have in the past? In June, as I got on the plane to fly back from the National Association of Hispanic Journalists convention, a young woman cried out: “Michael Jackson died!” Using my iPhone, I Googled “Michael Jackson died.” Several reports showed up—all from years long-gone. His was a much-rumored death. So I checked Twitter, and found the TMZ report—couched in some skepticism from my tweeps. On to the Los Angeles Times, where Jackson was still in a coma. Now the flight was leaving. Not until I landed did I get the confirmation I itched for: the Times, quoting the coroner.

But what if TMZ had quoted the coroner? Would I have stopped there?

This raises questions about what verification means in this age of social media. And what is journalism’s role in making sure information is verified? It strikes me that most people don’t care as much about who publishes news (or what are often rumors) first these days as they do about whether the sites they rely on have it right when they want it. Now, as we all know, news and information need to be on the platform we’re checking, wherever we are.

Being there and being accurate are how journalistic credibility is brought to the social media ocean. Yet many legacy media have fallen behind in delivering this one-two punch combination. While it’s a given that there will always be a need for reliable verification, what must be better understood is how people seek out news and information and how they learn through their use of social media.

Recently, the MacArthur Foundation’s John Bracken and I talked about the process by which an online community or group digests an event and comes to an understanding of it in real time. This happens among Facebook friends or people whose tweets we follow or folks who create new records of events on Wikipedia. The question well worth asking is where journalism fits in this fast-emerging and ever-changing social media and digital ecosystem.

During a June conference, “Beyond Broadcast 09,” held at the University of Southern California’s Annenberg School of Journalism, conversations ranged from the information needs of communities to democratizing the language of online storytelling, from maintaining editorial quality to enabling dialogue and the future of public service media. Each topic discussed was central to the future of journalism. Yet, never in the three days we were together did I once hear the word “journalism” mentioned. From there I went to a conference at MIT, where the organizing theme was “civic media.” In many of these situations, I find myself using the term “information in the public interest.” In all these cases, however much journalistic values and practices might be evident, the term itself is absent.

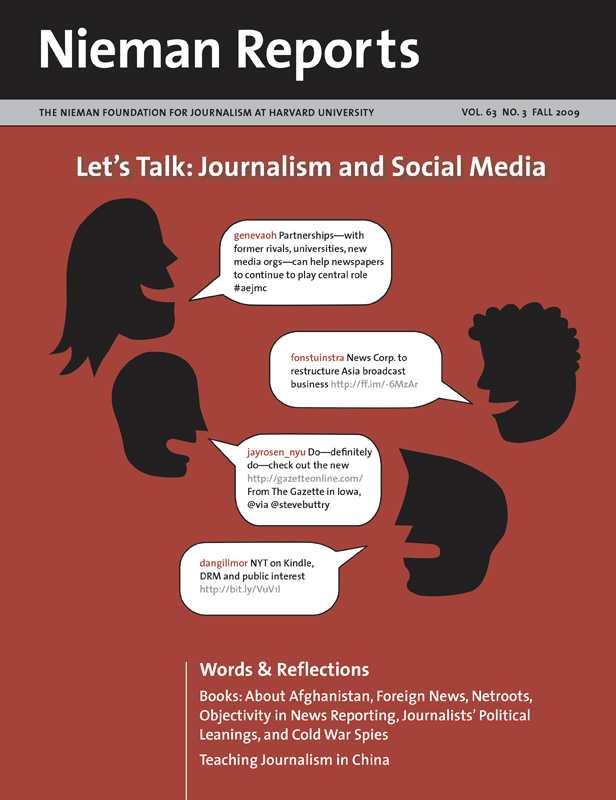

Geneva Overholser’s Facebook page.

Journalism: The Missing Ingredient

I’m not suggesting that journalism—as a word, a concept, and a craft—has gone away or is no longer important. I’m saying that those of us who ground ourselves in what we know to be an ethically sound and civically essential mode of information gathering and information dissemination have to find a way to be in these conversations—whatever we call the conversations or ourselves. Our job is to keep an eye on the public interest. Bringing our journalistic values to these environments that have captured the imagination of millions is one of the most promising ways we have of serving that interest.

Too often, it seems, those of us who’ve been about building community through our journalism seem to assume a kind of “how dare they?” attitude toward those who construct communities through social media. We’ve got to get over that. People are vastly more powerful now as consumers and shapers of news. The less loudly journalists applaud this development, the further behind we’ll be left until we fade to irrelevance.

Accuracy, proportionality and fairness, as time-honored journalistic values, are well worth adoption by those conversing through social networks. Useful, too, would be journalism’s (albeit imperfect) emphasis on including a broad range of voices. Cool as a lot of these social networks are, they can be extremely cliquish. Witness the prevailing Twitter discussions about whither journalism, often filled with more strut than substance, lacking both historical and international context and begging the question: If the Web is all about democratization, how come everybody in the debate sounds like a 19-year-old privileged male?

In the Classroom

Finally, how do we bring social media into the academy? So far, we at Annenberg have done it patchily by bringing in folks to do series of workshops for students and faculty. We’ve had regular discussions with digital media innovators throughout the year. One challenge, of course, is that people’s level of understanding and comfort is all over the place. Moreover, when the students learning about social media are 18-year-olds, most are already swimming comfortably in these waters. Yet, they do need to ponder—and practice—the new sensibilities required of them now that they will swim there as journalists.

Integrating the questions and issues and tools into everyday classroom discussion is critical. When the focus is on journalistic ethics, the geopolitical implications of social networks’ role belong in that discussion. In lessons revolving around entrepreneurial journalism, there needs to be woven into the conversation the issue of how journalists handle their personal engagement in social networks. Along with this would come discussion of how they “brand” themselves for a future that is likely to include a lot of independent activity.

At Annenberg, we’ve now hired digital innovators and observers—Andrew Lih, author of “The Wikipedia Revolution,” Robert Hernandez, who executed the vision for The Seattle Times’ Web site, and Henry Jenkins, who directed MIT’s Comparative Media Studies program. Using their ability to weave experiences and knowledge into our curricula, we know that social media will become integral to what is taught in our journalism classes. Timely discussions of emerging examples of social media’s influence on journalism and vice versa must continue, as well.

The journalism academy has another important role to play. It’s the natural home for substantial analysis and research exploring the impact of social media on learning, on the processing of information, and on the civic dialogue. As journalists come to understand the nature and value of information being gathered and conveyed through various social networks, they will not only act more effectively in this new and vital world. They will also enhance the prospects for journalism’s long-term survival.

Geneva Overholser, a 1986 Nieman Fellow, is the director of the University of Southern California’s Annenberg School of Journalism.

It is essential to begin by understanding various social media sites and the ways they can enhance the work journalists do. A regular perusal of sites like 10000words.net and savethemedia.com is a great way to do this. But how do we move beyond acquainting ourselves with this world and actually figure out how to “use” it for journalism, which requires understanding its nature and impact on participants and on public life?

What does it mean to journalists, for example, that people are in large measure obtaining, and shaping, their information so differently than they have in the past? In June, as I got on the plane to fly back from the National Association of Hispanic Journalists convention, a young woman cried out: “Michael Jackson died!” Using my iPhone, I Googled “Michael Jackson died.” Several reports showed up—all from years long-gone. His was a much-rumored death. So I checked Twitter, and found the TMZ report—couched in some skepticism from my tweeps. On to the Los Angeles Times, where Jackson was still in a coma. Now the flight was leaving. Not until I landed did I get the confirmation I itched for: the Times, quoting the coroner.

But what if TMZ had quoted the coroner? Would I have stopped there?

This raises questions about what verification means in this age of social media. And what is journalism’s role in making sure information is verified? It strikes me that most people don’t care as much about who publishes news (or what are often rumors) first these days as they do about whether the sites they rely on have it right when they want it. Now, as we all know, news and information need to be on the platform we’re checking, wherever we are.

Being there and being accurate are how journalistic credibility is brought to the social media ocean. Yet many legacy media have fallen behind in delivering this one-two punch combination. While it’s a given that there will always be a need for reliable verification, what must be better understood is how people seek out news and information and how they learn through their use of social media.

Recently, the MacArthur Foundation’s John Bracken and I talked about the process by which an online community or group digests an event and comes to an understanding of it in real time. This happens among Facebook friends or people whose tweets we follow or folks who create new records of events on Wikipedia. The question well worth asking is where journalism fits in this fast-emerging and ever-changing social media and digital ecosystem.

During a June conference, “Beyond Broadcast 09,” held at the University of Southern California’s Annenberg School of Journalism, conversations ranged from the information needs of communities to democratizing the language of online storytelling, from maintaining editorial quality to enabling dialogue and the future of public service media. Each topic discussed was central to the future of journalism. Yet, never in the three days we were together did I once hear the word “journalism” mentioned. From there I went to a conference at MIT, where the organizing theme was “civic media.” In many of these situations, I find myself using the term “information in the public interest.” In all these cases, however much journalistic values and practices might be evident, the term itself is absent.

Geneva Overholser’s Facebook page.

Journalism: The Missing Ingredient

I’m not suggesting that journalism—as a word, a concept, and a craft—has gone away or is no longer important. I’m saying that those of us who ground ourselves in what we know to be an ethically sound and civically essential mode of information gathering and information dissemination have to find a way to be in these conversations—whatever we call the conversations or ourselves. Our job is to keep an eye on the public interest. Bringing our journalistic values to these environments that have captured the imagination of millions is one of the most promising ways we have of serving that interest.

Too often, it seems, those of us who’ve been about building community through our journalism seem to assume a kind of “how dare they?” attitude toward those who construct communities through social media. We’ve got to get over that. People are vastly more powerful now as consumers and shapers of news. The less loudly journalists applaud this development, the further behind we’ll be left until we fade to irrelevance.

Accuracy, proportionality and fairness, as time-honored journalistic values, are well worth adoption by those conversing through social networks. Useful, too, would be journalism’s (albeit imperfect) emphasis on including a broad range of voices. Cool as a lot of these social networks are, they can be extremely cliquish. Witness the prevailing Twitter discussions about whither journalism, often filled with more strut than substance, lacking both historical and international context and begging the question: If the Web is all about democratization, how come everybody in the debate sounds like a 19-year-old privileged male?

In the Classroom

Finally, how do we bring social media into the academy? So far, we at Annenberg have done it patchily by bringing in folks to do series of workshops for students and faculty. We’ve had regular discussions with digital media innovators throughout the year. One challenge, of course, is that people’s level of understanding and comfort is all over the place. Moreover, when the students learning about social media are 18-year-olds, most are already swimming comfortably in these waters. Yet, they do need to ponder—and practice—the new sensibilities required of them now that they will swim there as journalists.

Integrating the questions and issues and tools into everyday classroom discussion is critical. When the focus is on journalistic ethics, the geopolitical implications of social networks’ role belong in that discussion. In lessons revolving around entrepreneurial journalism, there needs to be woven into the conversation the issue of how journalists handle their personal engagement in social networks. Along with this would come discussion of how they “brand” themselves for a future that is likely to include a lot of independent activity.

At Annenberg, we’ve now hired digital innovators and observers—Andrew Lih, author of “The Wikipedia Revolution,” Robert Hernandez, who executed the vision for The Seattle Times’ Web site, and Henry Jenkins, who directed MIT’s Comparative Media Studies program. Using their ability to weave experiences and knowledge into our curricula, we know that social media will become integral to what is taught in our journalism classes. Timely discussions of emerging examples of social media’s influence on journalism and vice versa must continue, as well.

The journalism academy has another important role to play. It’s the natural home for substantial analysis and research exploring the impact of social media on learning, on the processing of information, and on the civic dialogue. As journalists come to understand the nature and value of information being gathered and conveyed through various social networks, they will not only act more effectively in this new and vital world. They will also enhance the prospects for journalism’s long-term survival.

Geneva Overholser, a 1986 Nieman Fellow, is the director of the University of Southern California’s Annenberg School of Journalism.