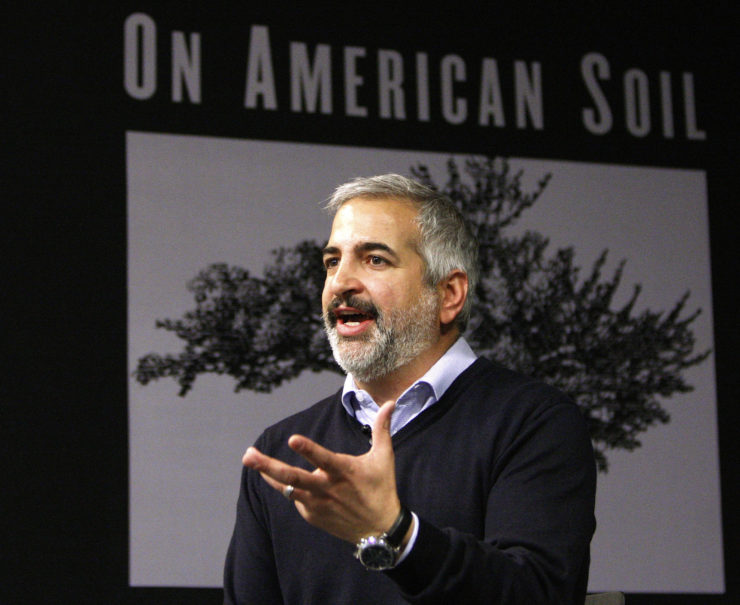

In life and death alike, Anthony Shadid was repeatedly recognized by his peers as among the finest foreign correspondents of his generation. To examine his legacy and share it with journalism students and the wider world, I am leading a one-year project at the American University of Beirut (AUB), co-sponsored by the Media Studies Department and the AUB Libraries Archives, with the cooperation of Anthony’s widow Nada Bakri Shadid. I am a professor of journalism and journalist in residence at AUB, home to Anthony’s personal papers and library. Our project will organize and make available an archive of his work.

Drawing on my research to date, I teach a course at AUB called “Narrative News Reporting and the Legacy of Anthony Shadid.” I knew Anthony throughout his 15 years of covering the Middle East for the Associated Press, The Boston Globe, The Washington Post, and The New York Times. Like so many others, I admired the almost musical flow of his prose that captured the sentiments and conditions of the people he portrayed across the Arab world. His stories ranged far and wide—Iraq under attack, Palestine at war, Cairo in revolution, a Jordanian roadside coffee vendor.

I have been reviewing Anthony’s personal papers, reading 350 articles he wrote while covering the Middle East, and interviewing his former colleagues and associates. I now appreciate better why Anthony won several major awards, including two Pulitzers, and was widely sought as a speaker. His diligent reporting and organizing were craft techniques that any serious journalist could master; more rare was his very personal determination to convey the stories and sentiments of Arab people in a way that had never been done before.

Three aspects of his work stand out. First, his reporting always centered on the lives and sentiments of ordinary people. He wrote about men and women living in exploding cities and neglected villages, not because they captured a bigger story, but because they were the story that would shape the future of their countries. Second, his reporting was immersive and relentless. He probed every street, room, memory, torn chocolate wrapper, shattered window, and mother’s smile or frown in sight. He listened intently and empathetically for hours or days, in order to hear, capture, and relay the sentiments of ordinary people. Third, he organized his wealth of reporting details with great diligence. He transcribed his notes and interviews, pulled from them the core story he wanted to tell, and wrote a detailed story outline with themes, leads, quotes, characters, emotions, color, and ending that had all the look and feel of a mini movie script. And then he wrote.

Drawing on my research to date, I teach a course at AUB called “Narrative News Reporting and the Legacy of Anthony Shadid.” I knew Anthony throughout his 15 years of covering the Middle East for the Associated Press, The Boston Globe, The Washington Post, and The New York Times. Like so many others, I admired the almost musical flow of his prose that captured the sentiments and conditions of the people he portrayed across the Arab world. His stories ranged far and wide—Iraq under attack, Palestine at war, Cairo in revolution, a Jordanian roadside coffee vendor.

I have been reviewing Anthony’s personal papers, reading 350 articles he wrote while covering the Middle East, and interviewing his former colleagues and associates. I now appreciate better why Anthony won several major awards, including two Pulitzers, and was widely sought as a speaker. His diligent reporting and organizing were craft techniques that any serious journalist could master; more rare was his very personal determination to convey the stories and sentiments of Arab people in a way that had never been done before.

Three aspects of his work stand out. First, his reporting always centered on the lives and sentiments of ordinary people. He wrote about men and women living in exploding cities and neglected villages, not because they captured a bigger story, but because they were the story that would shape the future of their countries. Second, his reporting was immersive and relentless. He probed every street, room, memory, torn chocolate wrapper, shattered window, and mother’s smile or frown in sight. He listened intently and empathetically for hours or days, in order to hear, capture, and relay the sentiments of ordinary people. Third, he organized his wealth of reporting details with great diligence. He transcribed his notes and interviews, pulled from them the core story he wanted to tell, and wrote a detailed story outline with themes, leads, quotes, characters, emotions, color, and ending that had all the look and feel of a mini movie script. And then he wrote.