This call to action, accompanied by a doctored image of Combs wearing a “Vote and Die” T-shirt, mutated into a grim commentary on Covid-19’s ongoing impact on the ballot and highlights growing anxiety around voting during the pandemic. In the United States, these concerns are intensely partisan, as the incomplete Democratic primaries are already beginning to force changes to how we vote.

The United States has a long history of disenfranchisement and voter suppression; struggles to achieve full voting rights are targeted by disinformation campaigns to keep already marginalized voters home on Election Day. As more of our political communication moves online, concern grows that misleading information is being micro-targeted to impact national and local elections.

Research indicates that online voter suppression campaigns are tailored across race, class, and age. But, there is a gap in understanding how Covid-19 or health disparities may contribute to voter suppression.

Grim parody slogans like “Vote and Die” help illuminate collective anxieties and anticipate a new political reality. The promise of the internet to increase democratic participation is being hijacked by disinformation and authoritarian regimes, all of which is accelerated by the global pandemic. The coming year may be witness to the largest challenge to voting rights since the civil rights era, and failures in the media ecosystem may intensify its impact.

Even absent a pandemic, it is difficult to create equitable and accessible voting conditions. Efforts include ride-shares, increasing early voting and the number of polling places, and same-day registration. After the Russian Internet Research Agency scandal, there has been a tremendous push to get social media companies to thwart disinformation campaigns, so that voters are not impeded by false news when seeking information about voting. Taken together, these physical and informational obstacles alone would be enough to deter some voters. The pandemic both exacerbates and amplifies voter suppression.

Covid-19 will dramatically alter the mechanics of the national election. We anticipate three significant strains on voter participation: social distancing requirements curtailing transportation to voting locations, partisan opposition to mail-in ballots, and an accelerated politicization of the strained U.S. health care system.

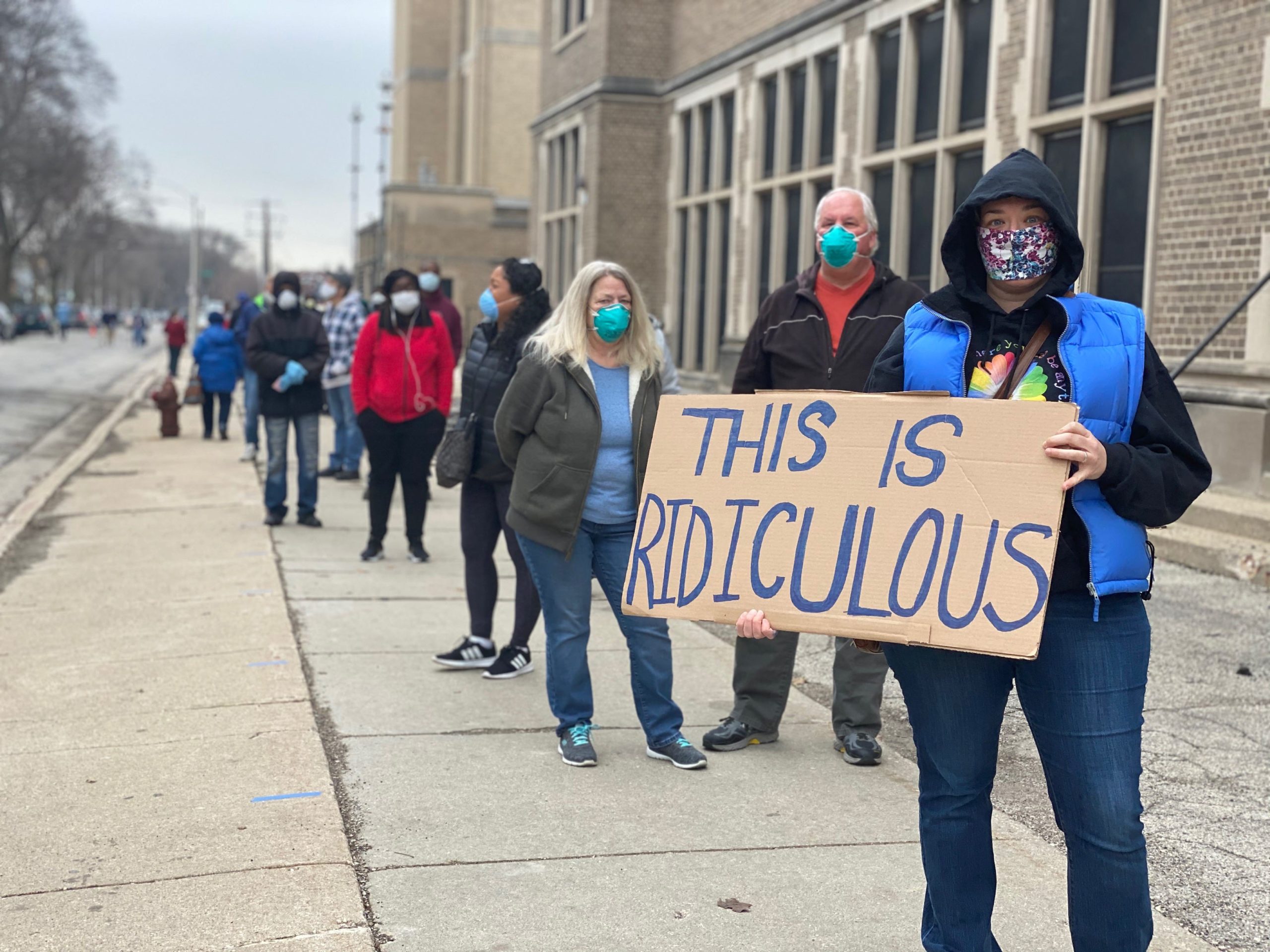

What happened in Wisconsin may foreshadow what's to come in November. Many Americans will likely still have to travel long distances to get to polling locations. Mobilizing these voters often depends on their ability to share rides or use public transportation. If social distancing is still in place, people can’t safely travel together. For the elderly, low-income, and those who live far away from their designated voting locations, carpooling and bussing become unsafe options. Carpooling and bussing are already attacked by the right in many states, and now with the reality of the Covid-19 pandemic, group travel is also physically dangerous.

Flawed communication technologies will continue to add the static of disinformation into these conversations about the equity, accessibility, and possibility of future elections. Even rumors of polling disruptions may be used by bad actors to deter people from coming out to vote.

Journalists, now more than ever, must help cut through the rampant disinformation around the pandemic and stop partisan attempts to prematurely delegitimize election results. Timely, relevant, and local reporting has become more crucial than ever, but finding sources and conducting investigations are going to be much more difficult as social distancing means there are far fewer opportunities for fact-finding.

Plans for the expansion of mail-in ballots for primaries have been suggested by prominent Democrats. President Trump and Republican lawmakers are already pushing back, claiming mail-in ballots are ripe for manipulation. This mirrors the paranoia of supposed voter fraud that fuels voter suppression campaigns in states like Alabama. At the same time, Republican leaders are also further eroding institutional trust; Senator Ted Cruz has said the Democrats and media are “rooting” for a disaster and Trump has called mail-in ballots a haven for fraud.

When the ability to vote becomes constrained by reluctance to accept mail-in ballots, the already marginalized communities with the most at stake will be hit hardest. It is apparent that already fragile voting processes need to change, but as changes are introduced, the opportunity for manipulation and misinformation about voting increases.

As barriers to voting increase due to physical safety, strained healthcare systems will become central topics of electoral politics. Medical insurance is going to become a flagship issue for these elections, particularly with tens of millions of Americans out of work or underemployed. Alarming trends in the data show that Covid-19 is spreading fast in low-income communities and is fatal for high numbers of African-Americans and the elderly. As both Republicans and Democrats struggle with their party positions on Medicare expansion, controlling the narrative on healthcare will become central.

Marginalized communities are being hit hardest by Covid-19 and their participation will be suppressed even further without grassroots organizing. It’s not just a question of how voter suppression will happen, but also how many people will be unable to vote. Journalists would do well to forge closer connections with civil society organizations that are taking on voting rights as a central issue during the pandemic.

A healthy democracy depends on reliable information so people feel like they’re making sound decisions. This information is the responsibility of federal and local governments to disseminate. We rely on journalism to hold these bodies accountable and point out where we are being deceived. The media demand for Covid-19 information has been accompanied by deficient information flows around the election process itself, and the fixation on social media drowns out important news and updates.

Due to Covid-19 and the ensuing economic crisis, covering elections will require the collaboration of civil society, state agencies, social media companies, and news organizations. Democracy is a process that must be organized, accountable, and transparent. While the virus respects no human timeline, November 3rd is still on its way. We don’t have a second to waste.