Sometimes I wonder if I am crazy to be covering the issue of human trafficking as a photographer. That’s when I realize how life can have its own way of deciding such things; it’s what I’ve been compelled to do. Nothing about this job makes it easy—there’s the photographic challenge of getting shots of criminal activity, which by its very nature is clandestine. Equally difficult is bearing the weight of absorbing and communicating the unrelenting pain of the victims.

Yet this is what I do, and so my journey brings me face to face with many victims of the global trafficking of human beings, most of whom are women, many still children. In most cases they are helpless to escape the horror of what their lives have become, though some do. In hearing their stories and, in some cases, following their journey of recovery, I have come to understand the interwoven layers of my responsibility—as a photographer, a journalist, and a human being.

Related Article

“Modern-Day Slavery: A Necessary Beat—With Different Challenges”

– E. Benjamin Skinner

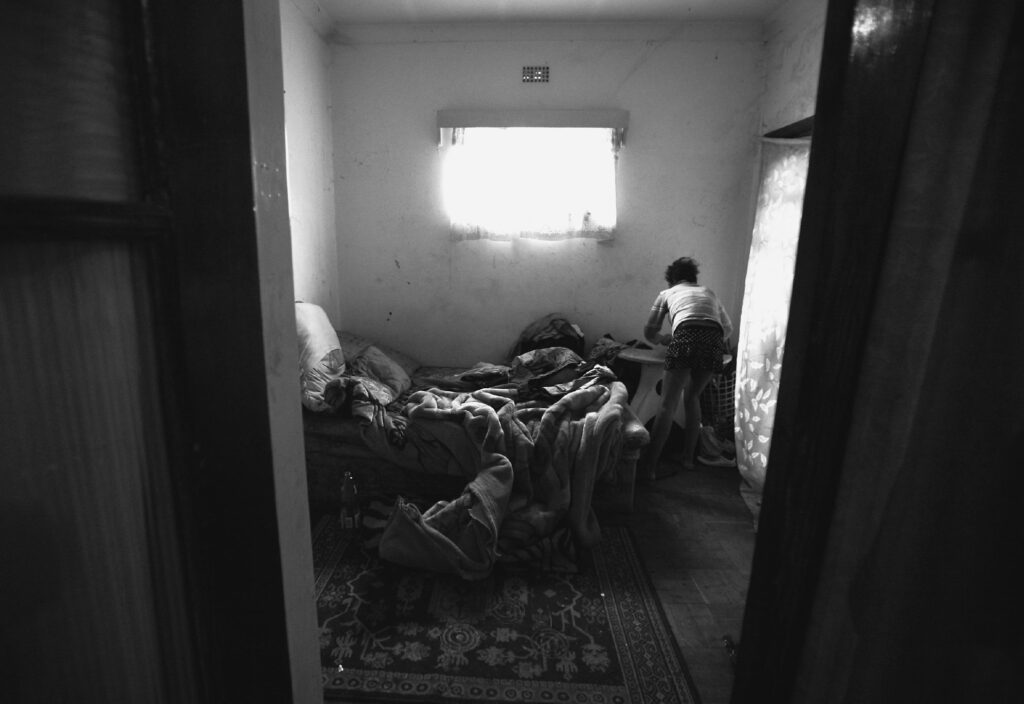

The pursuit of any documentary photographer or photojournalist is to tell a story visually—so the image conveys the story without the necessity of words. To do this, I find ways to personify the issue, to bring an abstract subject into the realm of reality. Data about human trafficking, while horrifying to learn, can’t do justice to this story: Visual images—with the capacity to draw us in to another human being’s existence—have a vital role to play as powerful storytelling vehicles. Absent this personal connection, people remain detached.

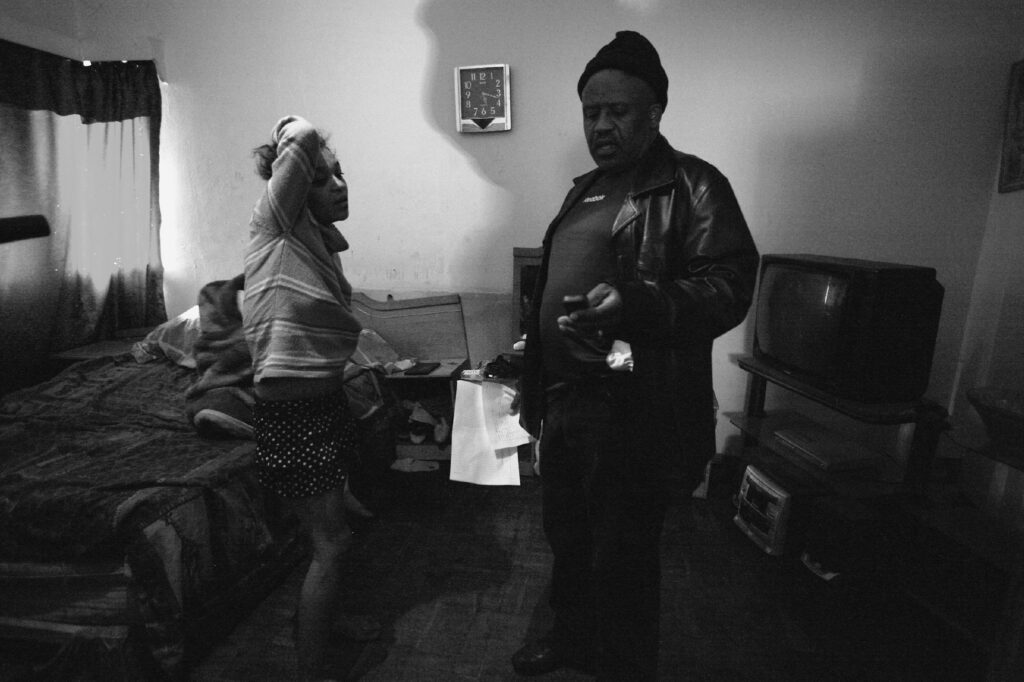

The fine line between being a journalist and being someone who exploits a victim has become clear to me in my attempt to cover this story. During the past year, as I have met with women and young girls who were victims of domestic sex trafficking in South Africa and with social workers who work with victims who have escaped, I have more fully understood the human dimensions of this issue—and how it connects to our efforts to report on these lives. Merely by retelling her story, a victim can be retraumatized, severely complicating her recovery. For minors, the risk is even greater since the level of manipulation and trauma they’ve been exposed to often leaves them with severe psychological problems.

I experienced this with the first young woman I spoke to in South Africa who had been trafficked. She was 17 years old and had been entrapped in this circumstance for five years before she escaped and found refuge. Even after she was “safe,” she suffered from psychotic spells; the effects of her trauma meant that she could not recall with any certainty the timeline of her experiences. Soon after she related her story to me, I learned that she had relapsed into a mental health crisis. Additionally, questioning victims too early (or at all) can risk jeopardizing possible police investigations, which in South Africa are frustratingly more the exception in such cases than the rule.

As a photographer I often ask myself whether what I’m doing is in the victim’s best interest. I use visual images to tell a story; it’s how I communicate a person’s humanity, how I convey their pain and anguish or their hope for and pursuit of survival. I’ve come to accept that it is not always possible for me to remain emotionally detached, as much as I might feel this to be a journalist’s obligation.

When human trafficking surfaced as a story during the World Cup in South Africa, numerous reporters sought me out, and they asked me “Can you get me a victim?” The insensitivity of their request hit me hard, revealing the ugly side of journalism. Insensitive sensationalist reporting of human trafficking—conveying little beyond the hype of headlines based on hugely exaggerated speculation—has led to a media backlash. The surge of misinformed reporting during the World Cup resulted in small but unrealistic expectations that government or legal authorities would respond in some positive way and in the public’s belief that once the World Cup left the stage, so, too, would the issue of human trafficking. It was as if South Africans convinced themselves that something foreign arrived with the sports event—and would be gone when the games were over.

Yet the truth is that human trafficking, even though it hadn’t been covered by the news media, has been part of the migrant flow into South Africa for decades. Nor does it happen only to women who aren’t South African. And eradicating it will not take place in a vacuum.

Similarly, reporting about it needs to be embedded in the complexities of how this nation’s poor women and children are marginalized—and yes, trafficked—as they confront obstacles in acquiring an education and in being kept healthy and safe. It should surprise no one that human trafficking is happening in this country in which two-thirds of children live in poverty and sex crimes against women and children climb year after year, and yet these crimes remain among the least of the government’s priorities.

Through my photography I work to reveal the reality and horror of human trafficking. Yet in doing so I am acutely aware of the traumatic scars these experiences leave inside their victims. Being a journalist does not give me the right to invade their lives in ways that will reignite their pain.

Melanie Hamman is a photographer whose work on child protection and trafficking was exhibited in late 2010 at Constitution Hill in Johannesburg, South Africa [PDF]. Her photographs also accompanied a story about human trafficking by E. Benjamin Skinner in Time magazine in early 2010. She has developed a website to which journalists can go for information about covering human trafficking: www.mediamonitoringafrica.org/cpt.