Clichy-sous-Bois residents walk past the wreckage of a burned car in a suburb east of Paris. November 2005. Photo by Jacques Brinon/The Associated Press.

Many in the international press interpreted November's riots by poor, minority youth who live in congested French suburbs as new testimony of France's weakness. In some publications, the crisis was referred to as a "civil war." Newsweek headlined its coverage "Europe's Time Bomb," and Time claimed that "Paris is Burning," while explaining that "nights of mayhem scorch France's troubled banlieues and blacken the country's image of itself."

As suburban riots continued day after day, French news media leaders became increasingly embarrassed by the spectacle. They knew that the public gravitates to violent events, no matter where they take place. Yet these French media executives also knew that giving too much attention to the riots would only dramatize the situation more. Even as rioters shouted hatred of the media, they worked hard to obtain maximum coverage of their neighborhoods. A kind of competition for the number of cars destroyed by fire took place. A week or so into the rioting, several TV producers decided not to inform viewers daily about the number of burned cars in specific areas. (During the three-week period of rioting, the total was more than 8,000.)

In this atmosphere, reporters had to move in teams, sometimes wearing helmets. They tried to work away from the local police to protect press independence and also get more accurate accounts from rioters. Yet they did not want to move too far away, fearing at times for their own security. Nor did they want to miss any crucial episodes in this story, since there were, of course, many violent confrontations between the protestors and police. After several of the correspondents had been insulted or attacked, editors selected special reporters — such as those who were better able to speak Arabic — to cover the story, and these reporters approached this assignment with a sense of heightened caution. A young French-Algerian journalist said that several years after working for a newspaper as an intern, that paper called him in November to propose a new assignment.

What French journalists reported on during the time of these riots diverged so much from the coverage that the international press gave to this story that the government organized a special briefing for foreign correspondents in Paris. Yves Bordenave, a reporter for Le Monde, says of decisions he made about coverage of this story: "We understood very fast that following smoke and flames would lead us nowhere. Only staying on the surface of things. ... We had to really enter the gangs to move further, though it was difficult and risky."

These events were not a French "civil war," nor did they degenerate into a new permanent form of insurrection. At the government briefing, spokesman Jean-François Coppé said that the image of "France on fire" was not accurate and called such coverage a "caricature" of the events. He even pointed out that such coverage had raised international fears that could hurt tourism and foreign investment. The intended effect did not appear to take hold. German journalists, for example, emphasized that France was the only European country in a state of emergency. Michaela Wiegel, from the Frankfurter Allgemeine, remarked that it was strange that the foreign press should be singled out, as if it were not reporting on the same events as the French press.

Broadly speaking, the problem is that these immigrants, most of whom are poor and who settled here after France's colonies achieved independence, have not been given opportunities to integrate into traditional French society. But neither do they want to give up their different ways of life to join the core of the French population. Suburban high-rise housing was built for them to live in, but they were weak, prefabricated buildings and within only a few years they have deteriorated. Also, beginning in the 1970's, unemployment strongly increased; some of today's teenagers are growing up in families in which no one has a job. Also, most of these families are Muslims and oppose anti-Islam attitudes, some of which have surfaced in the debate about women wearing a religious veil in France's public buildings, such as schools, which have been going on for more than a year.

It is certainly not the case that what goes on in these poor neighborhoods does not receive attention from the press in "normal" times. But the fact is that other political, social and economic issues are generally seen as greater priorities by the French press, which tends to concentrate its reporting on day-to-day hard-news stories. Nor have any of the successive French governments developed any real strategies to deal with these simmering issues or integrate these families into French society.

But once the riots broke out, several newspapers, radio and TV reports focused on the poor level of education and the high number of students who drop out of school, a situation that has contributed to an astonishing 60 percent youth unemployment rate in some suburbs. As they worked to report this story, journalists struggled with language problems. Not only do many of these immigrant families not speak French, but the teenagers have developed their own way of talking, using an odd French-Arabic slang and inverting syllables of French words. Nor was it easy for journalists to avoid reverting to "war" vocabulary, especially at a time when it is so much in use in the international debate about Iraq. In addition, those in the press had to figure out how to use some of the inopportune remarks made by politicians. For example, Nicolas Sarkozy, the French minister of homeland security, spoke about the need to clean out the affected suburbs using a high-pressure water machine and referred to rioters as "rabble."

It was quite frustrating for members of the French press to receive much general foreign criticism about their country and its news media, given that many journalists felt they were covering the issue of the urban violence in greater depth. For sure, if more journalistic attention to specific suburban and immigrant issues could be paid in daily news coverage — rather than addressing them in the midst of violent outbursts — that would likely be a good thing for the future of French society.

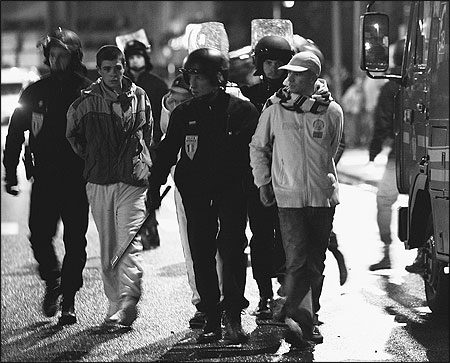

Riot police arrest youths in the Paris suburb, Le Blanc-Mesnil, early on November 3, 2005. Youths battled with police in Paris’s troubled suburbs for a seventh straight night, setting fire to a car dealership and hurling stones at police in at least 10 towns, officials said. Photo by Christophe Ena/The Associated Press.

Françoise Lazare, a 1998 Nieman Fellow, is a reporter with Le Monde in Paris.