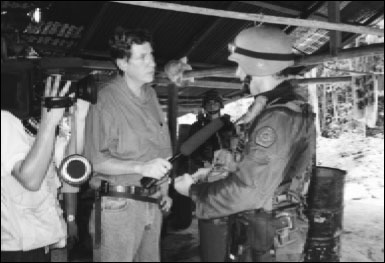

Univision TV reporter Raul Benoit interviews a Colombian National Police anti-narcotics trooper at a small, rustic coca leaf processing laboratory in the Catatumbo region of northeastern Colombia. Photo by Steve Salisbury.©

Nothing more clearly illustrates the daunting dangers Colombian journalists face than the number of their colleagues who were killed over the past decade as a result of their work: 34, according to research by the Committee to Protect Journalists (CPJ). This figure is unequalled by any country in Latin America; worldwide it is exceeded only by Algeria, where 58 journalists were killed in reprisal for their work over the same span of time.

With the continuing escalation of the nearly four-decade conflict that pits two major leftist guerrilla groups against the army and right-wing paramilitary forces, and with the peace process largely moribund, all warring factions are targeting journalists in efforts to control information. Over the last year, CPJ documented three cases of journalists killed in reprisal for their work. Numerous others were assaulted, threatened and kidnapped. Many fled into exile.

RELATED ARTICLE

"Truth in the Crossfire"

- Jineth Bedoya LimaThe shocking attack on Jineth Bedoya Lima illustrates the frightening challenges Colombian journalists must deal with. On May 25, 2000, Bedoya, a reporter at the Bogotá daily El Espectador, was kidnapped, beaten and raped. The attack apparently occurred in retaliation for the paper’s coverage of the United Self-Defense Forces of Colombia (AUC), the leading right-wing paramilitary group. During her ordeal, Bedoya’s assailants told her they planned to kill three other journalists, including Ignacio Gómez, the head of El Espectador’s investigative unit. The day before Bedoya was attacked, a man whom Gómez recognized as a member of the paramilitary forces tried to follow him into a taxi. Gómez fled the country less than a week later, after police told him that they could not provide protection.

RELATED ARTICLE

"Colombia’s War Takes Place on a Global Stage"

- Ignacio G. GómezAll sides in the conflict are acutely sensitive to how they are portrayed in the media, and all have resorted to violence to try to receive favorable coverage. The right-wing paramilitaries are the worst offenders, but journalists have plenty to fear from leftist guerrilla organizations as well. In 2000, CPJ documented numerous kidnappings by Colombia’s largest rebel groups, the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia (FARC) and the National Liberation Army (ELN); these acts of intimidation were carried out in efforts to influence the journalists’ work.

RELATED ARTICLE

"In Colombia, Journalists Have Many Enemies"

- Francisco SantosDuring the inauguration of peace negotiations in a guerrilla-controlled hamlet at the end of January 2000, FARC leader Manuel Marulanda told reporters that their bosses had been unfair to the FARC and would be made to pay. A prominent television personality, Fernando González-Pacheco, fled the country in March after receiving kidnap threats from the FARC. A week later, Francisco “Pacho” Santos Calderón, the editor of Colombia’s largest daily newspaper, El Tiempo, also went into exile after receiving credible reports of death threats and experiencing a suspected attempt on his life. According to one of Santos’s colleagues, the would-be assassins were hired by the FARC. Santos had founded a nongovernmental anti-kidnapping organization after Medellín drug cartel leader Pablo Escobar kidnapped Santos in 1990 and held him for eight months.

Violent attacks against the Colombian press in recent years were perpetrated largely by warring political factions rather than by the drug cartels that were responsible for so many deadly attacks against journalists during the late 1980’s and early 1990’s. But it is important to note that all sides in the conflict are partially financed through the drug trade. Some Colombian journalists worry that the U.S. government’s $1.5 billion military aid package, aimed at fighting narcotics, could lead to an intensification of the war and increase their vulnerability. “The question my colleagues and I ask ourselves is, who will be left to report on how the money is spent?” noted Gómez in a June 23, 2000 opinion piece published in The New York Times, just weeks after he had been forced into exile.

The attack on Gómez and his colleague Bedoya are illustrative not only because of the exile caused and the grisly violence involved, but also because of the impunity that surrounds these cases. Recently, Bedoya told CPJ that no one had been detained in relation to the attack and that the prosecutor in charge of the investigation had not even contacted her.

On August 18, 2000 the Colombian government established the Program for the Protection of Journalists and Social Communicators. A number of journalists, including Bedoya, have been supplied with bodyguards. But while this is a laudable gesture on the government’s part, having to drive around in the company of bodyguards clearly debilitates the ability of journalists to do their job. What is needed is that the perpetrators of crimes against journalists be brought to justice. But in a country with near total impunity for human rights abuses, those crimes go largely unpunished.

Colombian journalists continue to carry out their work in the face of enormous perils. As Gómez wrote in his New York Times op-ed, “We have always accepted the consequences for what we write, and we will continue to do so.”

Marylene Smeets is Americas program coordinator at the Committee to Protect Journalists in New York (www.cpj.org). CPJ’s annual report, “Attacks on the Press in 2000,” detailing the violence in Colombia and other countries during 2000, was recently published.