I was a journalism student at the University of California at Berkeley when I sent off a Freedom of Information Act (FOIA) request for Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) records concerning the university. I knew that during the 1950’s and 1960’s Berkeley had been involved in some of the nation’s biggest protests over academic freedom, free speech, and the Vietnam War. I also knew that congressional hearings in the 1970’s had revealed illegal FBI spying on thousands of Americans engaged in lawful dissent elsewhere. I was curious about what the FBI had been up to behind the scenes at Berkeley.

I had no idea I was embarking on a two-decade fight to get the FBI files or that I would bring three lawsuits under the FOIA that would reach the U.S. Supreme Court. Neither did I know that ultimately the FBI—which had denied snooping on campus—would release more than 200,000 pages showing that J. Edgar Hoover’s FBI conspired with the head of the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) to harass students and faculty, waged a covert campaign to get University of California (U.C.) President Clark Kerr fired, contributed to the 1966 defeat of Democratic Governor Edmund Brown, and provided secret political support to his successor, Ronald Reagan.

Nor did I envision that 20 years later, on June 9, 2002, the San Francisco Chronicle would publish my article disclosing these abuses of power and secrecy during the cold war, just as the FBI was once again being given vastly expanded power and secrecy in the war on terror, raising anew concerns about civil liberties and government accountability.

Federal bureaucracies have a long and well-documented history of needlessly stamping public records “confidential.” No administration has embraced the FOIA; President Johnson threatened to veto the new law in 1966, and President Ford vetoed the 1974 amendments that Congress nonetheless passed to strengthen it. But journalists in the post-September 11th world face what a Reporters Committee for Freedom of the Press study, “Homefront Confidential,” called “unprecedented” secrecy at the local, state and federal level.

By describing my struggle to obtain the FBI records about Berkeley, I hope to offer useful tips on how journalists can break down (and otherwise get around) government stonewalling on public records acts’ requests. Although my request was made under the FOIA, these suggestions also apply to local and state public records acts, which are often modeled on the federal law. And though my request was unusually large and complex, these tactics might be adapted to smaller and shorter-term requests.

Polide drag demonstrators from the steps inside San Francisco's City Hall, site of a House Un-American Activities Committee meeting in 1960. Photo by Bob Campbell/San Francisco Chronicle.

Investigating the FBI Files

My pursuit of the FBI files began at the Berkeley post office in 1981, when I mailed off a request seeking “any and all” records concerning U.C. I figured I’d get the files fairly soon. After all, the FOIA is the main federal law requiring timely public access to executive branch records. Agencies must grant or deny requests within 20 working days (or 30 if the request is voluminous or otherwise complicated). All executive branch records must be released unless the government specifically shows that the information falls under one or more of nine exemptions. Even if some parts of a record are exempt from release, all the other reasonably segregable parts must be released.

Months passed with no reply from the FBI. I filed an administrative appeal of the delay with the Justice Department, a prerequisite to filing a lawsuit. Finally the bureau sent a letter saying that processing the papers would cost about $35,000; it would gladly start as soon as I plunked down a 25 percent deposit. I asked the FBI to waive fees, which agencies must do if releasing the records would primarily benefit the general public. But in the bureau’s editorial judgment, there was no public interest. I was stymied.

Then in 1984, a pro bono lawyer took my case, and I sued for a fee waiver. While he handled the legal aspects of the case, I used my journalistic skills to show that releasing the records was in the public interest. In researching the 1964 Free Speech Movement (FSM), for example, I found news clips on the California legislature’s recognition of the FSM as an important civil rights event. I interviewed an expert on FBI records, who gave me a written declaration saying that administrative markings, handwritten notes, and other marginalia that often appear on FBI records were not meaningless but were substantive information about bureau operations. A historian gave me a declaration stating the requested records would provide new insight into historically significant events. All of this was submitted to the federal judge hearing my case. She ruled that I had “persuasively demonstrated” that my research “requires meticulous examination of record(s) that may not on their face indicate much to an untrained eye.” She said the FBI’s denial of a fee waiver had been “arbitrary and capricious.” She ordered the bureau to waive all fees.

With that roadblock gone, the FBI finally released about 5,000 pages. But they were so heavily censored I wondered if the bureau had become the nation’s largest consumer of Magic Markers. The FBI asserted that the information had to be withheld under several exemptions to the FOIA for information concerning national security, law enforcement operations, and the privacy of people named in the records.

By now I had taken a full time reporting job with The San Francisco Examiner. But I continued to work on the project on my own time. I believed the FBI’s secrecy claims were greatly exaggerated, and I’d become all the more curious about what the bureau was holding back.

I brought a second lawsuit challenging the deletions. The FBI, of course, could see what the censored material said; I could not. But my research about events in Berkeley gave me a good idea of what lay behind many of the Rorschach-like blotches. For instance, at the library I found decades-old Congressional reports that seemed to discuss subjects the FBI contended were still classified. I gathered obituaries of people who likely appeared in documents the bureau had excised on privacy grounds. (When a person dies, their right to privacy is greatly diminished.) I obtained notarized waivers from other people giving me permission to request their otherwise personal files.

I had some luck, too. While perusing a used bookstore, I came across a tell-all tome by a former FBI informer titled, “I Lived Inside the Campus Revolution.” Dates and events he discussed seemed to match those on some heavily deleted informant reports. I also found some FBI records released elsewhere that the bureau had blacked out in my case. This heightened my doubts about the bureau’s dire claims that releasing the same or similar information in the files I had requested would harm law enforcement operations or endanger national security.

My research also questioned whether some of the FBI’s investigations were undertaken for legitimate law enforcement purposes. If not, then the bureau couldn’t withhold information about them under the law enforcement exemption. The FBI had claimed that records on its investigation of the FSM should be withheld because they concerned a legitimate probe of possible violations of laws against riots and subversion. My research demonstrated that the FSM was engaged in nonviolent protests against a university rule that barred political activity on the Berkeley campus.

I contended that the FBI’s investigation of the FSM constituted improper political surveillance and that as a result the bureau could not withhold records about its inquiry under the law enforcement exemption. Likewise, the FBI claimed its investigations of U.C. President Clark Kerr were routine background investigations. My review of some of the released FBI records indicated that bureau officials had used the background investigation process as a pretext to undermine Kerr because they believed he was not tough enough on campus dissenters.

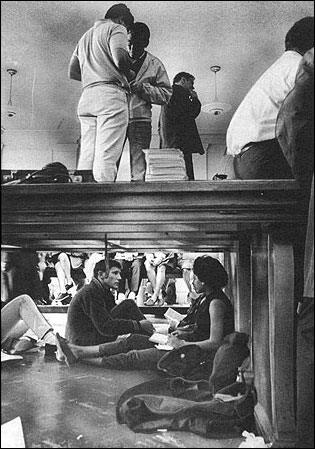

Double-decker sit-ins under and on top of tables at Berkeley's Sproul Hall in 1964. Photo by Peter Breinig/San Francisco Chronicle.

The Court Decides

All this material was submitted to the federal magistrate whom the judge had assigned to review the blacked-out documents. This process is called a “Vaughn” proceeding, after the federal court decision that established it. The requester and the federal agency each pick a number of sample documents and submit their evidence as to why the information should be withheld or released. The court then reviews each side’s arguments—and the uncensored records—in chambers.

A full year passed before the magistrate completed her line-by-line analysis. She ruled that most of the deleted information should be released. The Justice Department challenged the ruling before the U.S. District Court judge. In an opinion issued three years later, the judge upheld virtually all of the magistrate’s findings. The judge said I had presented “highly persuasive” evidence showing that though the bureau may have initially had legitimate ground to investigate the FSM, its inquiry devolved into unlawful political surveillance. The judge also said the FBI unlawfully targeted Kerr. The judge ordered the records released, saying they go to “the very essence of what the government was up to during a turbulent, historic period.”

The U.S. Department of Justice, which represents federal agencies in FOIA lawsuits, asked the judge to reconsider. She declined. The department appealed to the Ninth Circuit U.S. Court of Appeals, arguing that judges have no authority to question whether FBI records concern legitimate law enforcement and that the courts must therefore defer to the bureau’s decisions to keep records secret. If upheld, that position would have pulled the teeth of judicial review right out of the Freedom of Information Act.

Three more years passed. In a unanimous 1995 opinion written by a Reagan appointee, the court affirmed virtually all of the District Court’s ruling. The appeals panel said FBI memos “strongly” suggested that the bureau sought to “harass political opponents of the FBI’s allies among the [university’s governing] Regents, not to investigate subversion and civil disorder.” The appeals court also said the records showed that “the FBI waged a concerted effort in the late 1950’s and 1960’s to have Kerr fired from the presidency of U.C.” Those documents, the court added, “strongly support the suspicion that the FBI was investigating Kerr to have him removed from the U.C. administration, because FBI officials disagreed with his politics or his handling of administrative matters.”

The Justice Department asked the appeals court to reconsider. The court said no. The department next asked the entire Ninth Circuit, which comprises federal appeals judges throughout the Western states, to review the decision en banc. No judge agreed. By now, five federal judges had ruled that the FBI repeatedly violated the FOIA by withholding public records that were in some cases 50 years old. Still, in 1995 the department asked the U.S. Supreme Court to review the appeals court’s decision.

Before the high court decided whether to hear the matter, the FBI agreed to settle by releasing more than 200,000 pages. To promote government accountability, the FOIA requires federal agencies to pay the legal fees of plaintiffs who prove information was wrongly withheld. So as part of the settlement, the FBI paid my lawyer’s fees of more than $600,000.

The court record shows the FBI spent more than 15 years and $1 million in tax dollars trying to suppress public records documenting its unlawful activities. Kerr, who died last year at 92, was one of the nation’s most respected educators. The FBI never found any evidence of misconduct by him. He was shocked when I showed him memos detailing the FBI’s campaign against him.

Lessons Learned

By now, I had moved to the San Francisco Chronicle, and this is where I first published my account of this multiyear FOIA effort. In response to the Chronicle story, titled “The Campus Files,” U.S. Senator Dianne Feinstein opened a formal inquiry into the FBI’s actions. She told FBI Director Robert Mueller that “as we have seen from this Chronicle article, FOIA is often the only way the American people can be assured of government accountability.” The New York Times observed in an editorial that “These accounts of the FBI’s malfeasance are a powerful reminder of how easily intelligence organizations deployed to protect freedom can become its worst enemy.”

My experience demonstrates that FOIA requests are most likely to succeed when they grow out of and are informed by regular reporting. Investigative journalism and routine beat coverage can not only point reporters to information they should request under public records laws, but also to obits, waivers, official studies, and other materials that can be used to overcome baseless secrecy claims. Public records laws do not require agencies to conduct research for requesters, beyond a reasonable search of their own files. But these additional materials can be submitted along with an explanatory cover letter and might help to educate the officials handling the request about why the information should be released.

Requests should specify the target information but be worded broadly enough to close loopholes. I discovered that the FBI initially searched for records on the “University of California,” but not for “California, University of” and other variations.

Of course, it’s important to keep copies of all correspondence with an agency and notes of any conversations with officials. This administrative record will become the basis of any suit challenging the agency’s failure to release public information and will be read by the judge. For the same reason, it is wise to be polite and professional in all dealings with the agency.

Many journalists don’t bother with records act requests. In fact, the biggest users of the FOIA are corporations seeking information on competitors and regulators. But FOIA requests are worth pursuing even if they take time to produce results. Reporters can easily submit a request, then periodically pursue it in between their other work on the beat or the projects team. One day, the post office might deliver a box of smoking guns.

I hope it does not take another 20 years to find out what the government is up to during these turbulent times. But I know it will be up to reporters, editors and news executives to make sure people find out. Public records laws can play a critical role in that mission—and in protecting the public’s right to know.

Seth Rosenfeld is an investigative reporter for the San Francisco Chronicle. His report on the FBI at the University of California during the cold war, “The Campus Files,” can be found at www.sfgate.com/campus, along with examples of documents the FBI tried to unlawfully cover up.