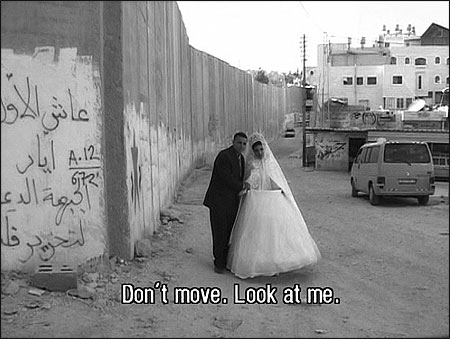

The just-married couple standing in front of a wall.

Journalists often say Israel and the Palestinian Authority are a news media paradise — an extraordinary news story, with uprisings following wars, invasions following uprisings in a seemingly unending cycle.

As an Israeli television news reporter and producer, I reported on my share of funerals, suicide bombings, political debates, and religious disputes — always striving for the most accurate information, thought-provoking sound bite, and heart-wrenching image.

In March 2002, at the peak of the second intifada, telling this news story felt less like paradise and more like hell. The words and images we broadcast were numbing, fatiguing and terrifying. Information failed to provide context or meaning. It seemed to me solid news reporting could no longer do its job.

I wondered whether documentary filmmaking could be a better way to tell a richer version of the truth. Could long-term reporting — a long-form project — find the vanishing context and restore meaning, while also filling in elusive emotional blanks?

I decided to find out by telling the story of couples starting their family life at just the time when Israel decided to prevent all residents of the Palestinian Authority from entering the country, including those married to Arab-Israeli citizens. Israel's new legislation virtually froze the life plans of thousands of Palestinian couples, preventing them from gaining legal status in Israel. It also stopped many others who were just about to marry.

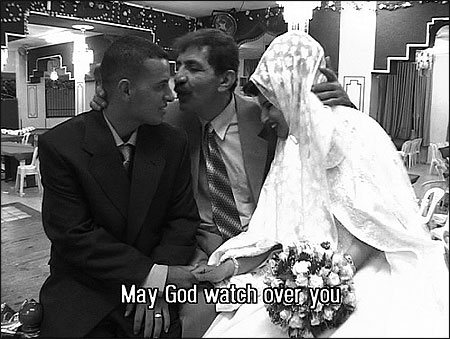

Top, Suhad at her wedding. Bottom, a soldier at the wedding car.

Revealing Lives, Telling Stories

Suhad Al Madbouh, a 23-year-old biology student from Bethlehem, fell in love with her fellow student Rabia, a Palestinian resident of Israeli-controlled East Jerusalem. They decided to get married, even though they knew that after the wedding Suhad would have to live illegally in her new home.

Early on, I made two central decisions: I would do no interviews, and the film would have no narration. Scenes would tell the story. I made this decision knowing that most viewers in my country have fixed political opinions, and this meant interviews would likely serve only to evoke debate, not dialogue.

The challenge for me was capturing Suhad's trajectory as an illegal Palestinian in Jerusalem without relying on any verbal accounts or reconstructions. This seemed almost an impossible mission. Through scenes I shot, I would need to show what happens to Suhad, and through her story to thousands of other permitless Palestinian women in Israel. I'd need to follow this illegal new wife as she walked down the street to the grocery store risking capture and deportation by the patrolling Israeli security forces. I'd have to find a way for viewers to watch Suhad, on her way back from visiting her family in Bethlehem, sneaking into Jerusalem through the cracks in the 25-foot-high concrete wall. And they'd need to see Rabia equipping Suhad with a borrowed Israeli ID to show soldiers so that he's not imprisoned for driving his illegal wife.

The catch is obvious. Having a camera crew present might attract unwanted attention and get Suhad into even greater trouble — a scenario that might destroy our relationship.

As things turned out, this documentary film ended up giving a detailed account of everything that did not happen. Suhad was almost caught by a border patrol jeep while taking a back road into Jerusalem after visiting her parents in Bethlehem to announce she is pregnant. As we trekked under the sun, we recognized the ominous honk of a border patrol jeep. The camerawomen and I stayed in the middle of the road while Suhad scurried into a nearby yard and hid behind the iron gate. The wireless microphone picked up her heavy breathing.

The military jeep stormed past us, never slowing down; Suhad was safe.

Another dramatic moment almost happened a month earlier — on her wedding day. Palestinian brides typically get stranded for hours at West Bank checkpoints and are then forced to get out of the decorated car, lift up their white dress, and trudge on high heels through the dust to the other side of the checkpoint, where they board a car with a different license plate. All these complications would have made a great scene for the film, but they never took place. That day, the presence of the camera helped Suhad rather than hurt her. When we reached the checkpoint, I ran straight past the long line of cars and up to the Israeli officer, begging him to let the convoy go. Flustered, I said: "I'm making a film about this couple and they are late for their wedding." Sure enough, they were allowed to go ahead, but I lost the coveted "bride in checkpoint dust" scene.

Or did I?

In the editing room, it turned out these almost scenes made my storytelling stronger. After all, it was the numbing effect of dramatic, violent news images that led me to filmmaking in the first place.

What I was discovering is how the long-form documentary allowed me to stop the hunt for the most striking newsworthy events. But still, the editing process was a daily struggle. The filmmaker in me pushed to pare the facts, eliminating what the journalist in me considered vital pieces of information and background.

In time, this agonizing process revealed the essence of the story. It demanded I focus, even dwell on the details; seemingly mundane domestic moments turned into stretched-out scenes. Before the wedding, one such scene was Suhad's father's tender gestures as he patiently sewed her veil. During the wedding, the couple's heads drew near during a spontaneous ceremony of passing the bride from father to husband, offering a blessing for her future. And at their new home, the silence of Suhad's married life was stressed visually as painfully slow camera movement revealed her solitude. In another scene there is a long close-up of her eyes as she fell asleep watching a television soap opera while her husband was away at work.

These longer scenes replace the customary images of Palestinians that Israeli's consume daily. Fresh moments penetrate viewers' imaginations, undercutting words, which are used all too often to justify violent actions. The documentary, entitled "Just Married," was shown on Israeli television and in film festivals and cinemas worldwide. In every screening, it attempts to build a space where emotions and thoughts form and flow, suspending judgment, prejudice and political conviction. To me, this is the power of film.

Top, The couple at their wedding ceremony being blessed by the father of the bride. Bottom, Suhad in her new home.

Ayelet Bechar, a 2008 Nieman Fellow, worked at ABC News and CNN in the United States after graduating from the Columbia University Graduate School of Journalism. When she returned to Israel, she worked as a TV news reporter and producer before leaving that job to become a documentary filmmaker. After making "Just Married," she directed "Power," a documentary about a young Bedouin Arab who volunteers to serve in the Israeli Army.