A young woman comments after a community screening of “Digital Divide," a Television Race Initiative documentary.

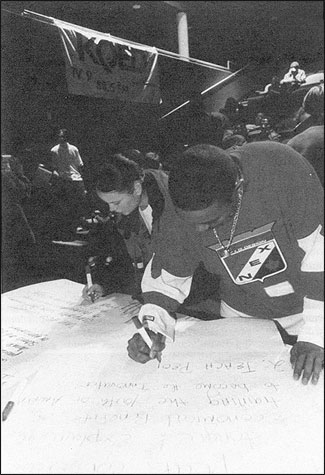

Bay Area youth act on what they’ve seen in “Digital Divide.”

Storytelling has brought communities together and enabled them to pass on knowledge since the dawn of time. Yet only recently have we, using television, begun to tap the enormous power of stories to stir collective action. A finely wrought documentary can set pulses racing—striking an emotional chord elusive to other forms of journalism.

Viewers called “P.O.V.,” the Public Broadcasting System’s independent documentary series, to say that “Rabbit in the Moon,” Emiko Omori’s first-person memoir on the internment of Japanese Americans during World War II, helped them raise painful buried issues with parents who had been imprisoned. Others wrote to say that a documentary on AIDS motivated them to volunteer at a hospice. And the most successful stories resonate across racial and class lines. When “Frontline” aired a piece on the SAT and meritocracy, students from the most privileged group—organized by a white high-school student in California who was incensed by what he learned—traveled to Sacramento to oppose standardized tests that gave them an unfair advantage.

I’m fascinated by these reactions, having long wondered how these raw responses of individuals lead to public conversations, sustained inquiry, or even citizen engagement. At a time when media images are so ubiquitous, our challenge is to transform visual essays into energizing resources, ones that people not only reflect on, but act on, ones that move them from being passive consumers to active participants.

Today, facilitated by relatively cheap digital cameras and editing systems, scores of filmmakers are painstakingly researching subjects that mainstream media ignore. They’re asking tough questions, searching for truth in claustrophobic editing rooms, and resisting pressure to dumb down their stories. Some cobble together the financial support to finish their work. A still smaller number find a national broadcast for their documentaries on one of few outlets for long-form journalism.

Understanding the potential such programming holds, in 1998 the Ford Foundation provided me with support to experiment with a media model that I called the Television Race Initiative (TRI). Since then, I’ve been working with a small team of facilitators and trainers to help a handful of communities and the public television stations that serve them use documentaries as powerful catalysts for addressing a range of local issues in which race is a factor.

The programs we’ve supported have been scheduled for broadcast on PBS and have ranged from long-form reportage such as “Facing the Truth with Bill Moyers,” his unflinching look at South Africa’s Truth and Reconciliation Commission, to Orlando Bagwell’s epic series, “Africans in America,” to an upcoming series, “The New Americans,” from the makers of “Hoop Dreams.” With support from the John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation, we’re now also working with documentaries that deal with issues beyond race, such as mental illness, the experience of being an adolescent girl, and handgun violence.

At TRI, we have two principal challenges: to identify documentaries and works in progress with the power to open up new ways of thinking about race or other neglected, critical and contentious issues, and to find ways of transforming raw individual responses into some group sensibility or conversation. We make a deliberate effort, in both cases, to work with as multicultural and diverse groups as possible—and, more importantly, the institutions that represent them.

In the process, we have found that the most effective films have an emotional honesty and personal voice that invite viewers to enter into a sort of relationship with the filmmaker. When we screened “P.O.V.”/ Deann Borshay’s film, “First Person Plural,” about her U.S. adoption from Korea, for a “brain trust” of multicultural leaders, we learned that it resonated not only among people who had adopted children from other nations, but among Native Americans who protested the placement of children from the reservation into urban families.

To explore ways in which these documentaries might result in action within specific communities, we seek advice from a variety of groups. We also seek partners in commercial and print media, foundations, faith-based organizations, and community groups to host sneak previews, community dialogues, and events that help build long-term alliances.

All of these elements came together in “Well-Founded Fear,” Shari Robertson and Michael Camerini’s stunning, two-hour film about the process of applying for political asylum. Filmed almost entirely in offices of the U.S. Immigration and Naturalization Service (INS), it focused on each person’s effort to persuade an officer of a “well-founded fear of persecution on grounds of race, religion, nationality, membership in a particular social group, or political opinion” in his or her home country. In case after harrowing case, a single interview determined who would stay in the United States and who would be sent home.

Our work with community leaders prior to the June 2000 broadcast of this documentary on “P.O.V.” assured a wide range of responses afterwards. In the San Francisco Bay area, a group of clergy decided to meet with INS officials in an attempt to improve conditions in the holding areas and offices where those interviews took place. In North Carolina, asylum attorneys received offers from other lawyers to work pro bono on asylum cases. In Minnesota’s Twin Cities, a community in which 75 languages are spoken, the program was the hook for organized dialogues among organizations that work with immigrant and refugee groups. In every one of these communities, conversations emerged about the “opportunity” to make one’s home in the United States and about what this country could and should stand for in this new era of globalization.

Some of the documentary filmmakers who work with us do so because they are activists and want to inspire collective action. Others bring a journalistic background to their work and do not take a position on how or whether their work triggers a community response. Regardless of the filmmaker’s orientation, our role in working with them remains the same: We want to encourage well-researched and powerful documentary work that offers people a way to engage in meaningful discussion about complex issues that have such an impact on how we interact with one another personally and politically. At a time when so many random bits of information are thrown at viewers from so many sources, there is abundant need for places to turn where thoughtful, engaging and sometimes provocative insights can be gleaned from visual storytelling. Those are the destinations that TRI is trying to create.

Ellen Schneider is executive director of “Active Voice,” a division of American Documentary, Inc. She was with “P.O.V.” for 10 years, most recently as executive producer.