In March 2010 Harper Collins published Saberi's book about her experiences in Iran, "Between Two Worlds"On May 10th, an appeals court in Iran suspended the prison sentence of American-Iranian journalist Roxana Saberi, who had been held in detention for more than three months. After being released from jail, she returned to the United States. In mid-April, Iran’s Revolutionary Court had charged her with spying for the United States and sentenced her to eight years in prison. This essay was written during the time Saberi was in Tehran’s Evin Prison about her and the challenging circumstances under which she and other journalists work in Iran.

She joined our improbable group halfway through the academic year and stuck it out until the end. In class she was calm, courteous and reserved. Her notes were assiduous, her questions intelligent. But she refrained from the cut-and-thrust that the rest of us thrilled in engaging in with our rather serious foreign ministry professors.

Roxana Saberi was self-possessed, unflappable and inscrutable.

EDITOR'S NOTE:

Iason Athanasiadis's reporting from Iran during the 2009 elections and its aftermath, supported by a grant from the Pulitzer Center on Crisis Reporting.We were a strange group even before Roxana, the Japanese-Iranian-American broadcast journalist beauty queen, joined us. There was a blonde Scottish Oxford graduate who managed to combine the flimsiest of mandatory headscarves with superb Persian delivered in an upper-crust British drawl; an American jurist who enthusiastically embraced her suffocating, government-mandated hijab long after it was spelled out to her that she could get away with less; a likeable South African diplomat in a perennial black “Reservoir Dogs” suit and string tie who was quiet for weeks at a time aside from occasional eruptions into frustrated, anti-imperialist screeds; a devout Saudi whose nationality was revoked after she met a Shi’ite Iranian fellow student at a university in the United States, married him and moved to Iran, and a Turkish diplomat about whom we learned very little except that he liked Iranian kebabs.

Roxana floated serenely over our rambunctiousness. She handed in her assignments on time, even while struggling to make ends meet as a freelance correspondent. Just before the end of the year, she received a summons to the ministry of education. If only such Sisyphean harassment of foreign students wasn’t the bread-and-circus of Iran’s rambling bureaucracy, the incident might have been prophetic.

Patient, punctual and self-possessed, Roxana went to the meeting. But the person she was supposed to see was not there, nor would he be back that day, an assistant told her as if arranging a meeting, skipping out on it, and then denying its existence was the most natural thing in the world. This charade played out a few more times until Roxana was told the reason behind her summoning: As a journalist, she was ineligible by Iranian law to receive her master’s degree.

No apparent logic was offered to explain the verdict. After all of her hard work, Roxana was denied her degree because of an unknown technicality. She knew how the system worked and that she could do nothing about it. She just had to put her head down and deal with it. As my endlessly frustrated Iranian friends never tired of reminding me, logic controls little in Iran.

This denial was only one of many frustrations imposed on Roxana as she struggled to live for her first time in Iran, work and reconcile her Iranian and Japanese identities with an American upbringing in North Dakota. When BBC World took her on in 2006 for the post of second correspondent, it was a long-awaited break. But a few months later, her accreditation was revoked and she was forced to return to low-profile freelancing.

Whenever I saw her, Roxana never betrayed the difficulties she was going through. She was always willing to help, pass on a contact, or inquire about my problems. She never mentioned that she was working on a book. But judging by her stoic character, a book she wrote would almost certainly have avoided the self-indulgencies of so many other expat memoirs that focus on personal journeys of self-discovery rather than the extraordinary, wonderful and deeply frustrating society that usually just provides the background.

Meanwhile, Roxana, her turquoise headscarf, videocamera and tripod were a fixture at press events. Her fluent Persian allowed her to give the kind of deep insight into the human side of Iran that is intentionally stripped away from the bombastic statements about Israel, threats to shut down the Persian Gulf, or announcement of fresh technological leaps.

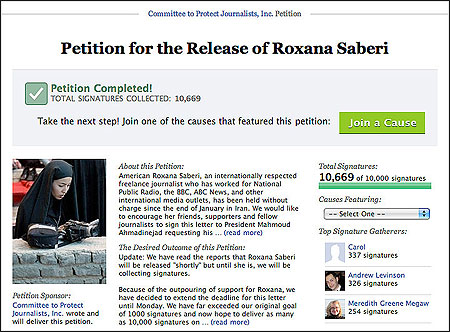

Intense international pressure was exerted by journalists and political leaders to urge the Iranians to release Roxana Saberi, which happened on May 10th.

Language, Meaning and Depth

Therein lies the rub. Roxana’s work consistently gave the lie to the narrative of a monolithic Islamic Republic. It went counter to the tension-escalating script that sees journalists focus on hard-line prayer sermons, anti-American demonstrations—dominated by government civil servants—and suicide-bomber registration drives, in which “bombers” register but don’t carry out an operation. It’s all part of Tehran’s never-ending baiting of Washington.

Roxana was no spy. Anyone who has experienced the difficulty of working as a journalist in Iran can tell you that researching a balanced story about the nuclear issue, let alone infiltrating the Islamic Republic’s deepest secrets, is near impossible. But Roxana was so good at what she did as to become a thorn. Her work cut away from the herd to focus on Iran’s tumultuous and deeply fascinating society. How disruptive this must have been for the regime’s painstakingly constructed image of a stiff upper-lipped Islamic society dedicated to revolutionary ideals rather than the proliferating plasma TVs and home appliances over which Iran’s materialistic postwar middle class (post-sanctions, they are now also nouveaux pauvre) salivate over.

There is a constant to Iran expelling journalists once they become too well versed in the country. Hyphenated Iranians, who cannot be expelled, instead experience the pressure being ratcheted up on them until residence there becomes unbearable.

Iran turned into a security state after the 2005 election of Mahmoud Ahmadinejad. Sanctions were imposed, the covert intelligence war between the Islamic Republic and the West swelled, and the authorities announced they had broken up several intelligence networks and carried out repeated sweeps of dissidents. Workers’ protests and a number of unexplained explosions rocked the country from 2005 onwards, putting the regime on edge. As correspondents for Agence France-Presse, The Associated Press, The Independent, The Guardian, and the Financial Times were barred, the foreign journalist exodus began.

Far better, Iran’s sphinx like bureaucrats thought, to give finite visitor visas to clueless, non-Persian speaking foreigners than to have permanently accredited (and bothersome) correspondents understanding the country and its culture. Instead, these outsiders would scoot around the Tehran-Qom-Isfahan triangle with their state-appointed guide, breathlessly interview a few regime-sanctioned reformists, indulge in some surreptitious flirting with Iran’s abundance of luscious womanhood, and come away mouthing similar platitudes about this “complex civilization,” “paradoxical” country, and “layered” society.

By summer 2007, Roxana, working without a press permit, was one of a very few journalists still surveying the scene. The night before I left Iran in 2007, an Iranian political analyst for a foreign embassy told me that the Iranian government abhors foreign journalists, who are seen as proffering “social intelligence” about their host country. Unlike truly locked-away lands such as North Korea, Iran is an open society proud of its contribution to world civilization. But the current security-minded regime wants to minimize the outflow of information.

Despite the abundance of information available about Iranian society, CIA agents allegedly speak Tajik-accented Persian, the kind of hillbilly squawk that might secure them road-construction jobs in provincial Iran but probably not high-level political access. Over at Langley, they watch Iranian cinema for clues about the target society or fish for scraps of information amid the exile communities in Los Angeles, Dubai and Baku.

The security-minded Ahmadinejad administration has sought to shut out information gathering of even the most innocent kind, an attitude diametrically opposed to the earlier Khatami administration’s emphasis on debate and openness. But even if the hard-line trend is now dominant—egged on by the Bush administration’s provocative and threatening maneuvers among Iran’s neighbors and Pentagon covert operations within its borders—journalists should not become sacrificial lambs.

Roxana and other journalists who reside in Tehran were massively hampered by existing in a state that viewed them as official spies. That was barrier enough to considering a freelance career as an intelligence informant. But what Roxana’s case reminds us—aside from the great disservice it did to Iran’s reputation—is that in our increasingly intertwined world journalists are not considered a protected species but treated as fair game.

Iason Athanasiadis, a 2008 Nieman Fellow and a freelance journalist in Iran between 2004 and 2007, wrote this article for The National, published in Abu Dhabi in the United Arab Emirates.

She joined our improbable group halfway through the academic year and stuck it out until the end. In class she was calm, courteous and reserved. Her notes were assiduous, her questions intelligent. But she refrained from the cut-and-thrust that the rest of us thrilled in engaging in with our rather serious foreign ministry professors.

Roxana Saberi was self-possessed, unflappable and inscrutable.

EDITOR'S NOTE:

Iason Athanasiadis's reporting from Iran during the 2009 elections and its aftermath, supported by a grant from the Pulitzer Center on Crisis Reporting.We were a strange group even before Roxana, the Japanese-Iranian-American broadcast journalist beauty queen, joined us. There was a blonde Scottish Oxford graduate who managed to combine the flimsiest of mandatory headscarves with superb Persian delivered in an upper-crust British drawl; an American jurist who enthusiastically embraced her suffocating, government-mandated hijab long after it was spelled out to her that she could get away with less; a likeable South African diplomat in a perennial black “Reservoir Dogs” suit and string tie who was quiet for weeks at a time aside from occasional eruptions into frustrated, anti-imperialist screeds; a devout Saudi whose nationality was revoked after she met a Shi’ite Iranian fellow student at a university in the United States, married him and moved to Iran, and a Turkish diplomat about whom we learned very little except that he liked Iranian kebabs.

Roxana floated serenely over our rambunctiousness. She handed in her assignments on time, even while struggling to make ends meet as a freelance correspondent. Just before the end of the year, she received a summons to the ministry of education. If only such Sisyphean harassment of foreign students wasn’t the bread-and-circus of Iran’s rambling bureaucracy, the incident might have been prophetic.

Patient, punctual and self-possessed, Roxana went to the meeting. But the person she was supposed to see was not there, nor would he be back that day, an assistant told her as if arranging a meeting, skipping out on it, and then denying its existence was the most natural thing in the world. This charade played out a few more times until Roxana was told the reason behind her summoning: As a journalist, she was ineligible by Iranian law to receive her master’s degree.

No apparent logic was offered to explain the verdict. After all of her hard work, Roxana was denied her degree because of an unknown technicality. She knew how the system worked and that she could do nothing about it. She just had to put her head down and deal with it. As my endlessly frustrated Iranian friends never tired of reminding me, logic controls little in Iran.

This denial was only one of many frustrations imposed on Roxana as she struggled to live for her first time in Iran, work and reconcile her Iranian and Japanese identities with an American upbringing in North Dakota. When BBC World took her on in 2006 for the post of second correspondent, it was a long-awaited break. But a few months later, her accreditation was revoked and she was forced to return to low-profile freelancing.

Whenever I saw her, Roxana never betrayed the difficulties she was going through. She was always willing to help, pass on a contact, or inquire about my problems. She never mentioned that she was working on a book. But judging by her stoic character, a book she wrote would almost certainly have avoided the self-indulgencies of so many other expat memoirs that focus on personal journeys of self-discovery rather than the extraordinary, wonderful and deeply frustrating society that usually just provides the background.

Meanwhile, Roxana, her turquoise headscarf, videocamera and tripod were a fixture at press events. Her fluent Persian allowed her to give the kind of deep insight into the human side of Iran that is intentionally stripped away from the bombastic statements about Israel, threats to shut down the Persian Gulf, or announcement of fresh technological leaps.

Intense international pressure was exerted by journalists and political leaders to urge the Iranians to release Roxana Saberi, which happened on May 10th.

Language, Meaning and Depth

Therein lies the rub. Roxana’s work consistently gave the lie to the narrative of a monolithic Islamic Republic. It went counter to the tension-escalating script that sees journalists focus on hard-line prayer sermons, anti-American demonstrations—dominated by government civil servants—and suicide-bomber registration drives, in which “bombers” register but don’t carry out an operation. It’s all part of Tehran’s never-ending baiting of Washington.

Roxana was no spy. Anyone who has experienced the difficulty of working as a journalist in Iran can tell you that researching a balanced story about the nuclear issue, let alone infiltrating the Islamic Republic’s deepest secrets, is near impossible. But Roxana was so good at what she did as to become a thorn. Her work cut away from the herd to focus on Iran’s tumultuous and deeply fascinating society. How disruptive this must have been for the regime’s painstakingly constructed image of a stiff upper-lipped Islamic society dedicated to revolutionary ideals rather than the proliferating plasma TVs and home appliances over which Iran’s materialistic postwar middle class (post-sanctions, they are now also nouveaux pauvre) salivate over.

There is a constant to Iran expelling journalists once they become too well versed in the country. Hyphenated Iranians, who cannot be expelled, instead experience the pressure being ratcheted up on them until residence there becomes unbearable.

Iran turned into a security state after the 2005 election of Mahmoud Ahmadinejad. Sanctions were imposed, the covert intelligence war between the Islamic Republic and the West swelled, and the authorities announced they had broken up several intelligence networks and carried out repeated sweeps of dissidents. Workers’ protests and a number of unexplained explosions rocked the country from 2005 onwards, putting the regime on edge. As correspondents for Agence France-Presse, The Associated Press, The Independent, The Guardian, and the Financial Times were barred, the foreign journalist exodus began.

Far better, Iran’s sphinx like bureaucrats thought, to give finite visitor visas to clueless, non-Persian speaking foreigners than to have permanently accredited (and bothersome) correspondents understanding the country and its culture. Instead, these outsiders would scoot around the Tehran-Qom-Isfahan triangle with their state-appointed guide, breathlessly interview a few regime-sanctioned reformists, indulge in some surreptitious flirting with Iran’s abundance of luscious womanhood, and come away mouthing similar platitudes about this “complex civilization,” “paradoxical” country, and “layered” society.

By summer 2007, Roxana, working without a press permit, was one of a very few journalists still surveying the scene. The night before I left Iran in 2007, an Iranian political analyst for a foreign embassy told me that the Iranian government abhors foreign journalists, who are seen as proffering “social intelligence” about their host country. Unlike truly locked-away lands such as North Korea, Iran is an open society proud of its contribution to world civilization. But the current security-minded regime wants to minimize the outflow of information.

Despite the abundance of information available about Iranian society, CIA agents allegedly speak Tajik-accented Persian, the kind of hillbilly squawk that might secure them road-construction jobs in provincial Iran but probably not high-level political access. Over at Langley, they watch Iranian cinema for clues about the target society or fish for scraps of information amid the exile communities in Los Angeles, Dubai and Baku.

The security-minded Ahmadinejad administration has sought to shut out information gathering of even the most innocent kind, an attitude diametrically opposed to the earlier Khatami administration’s emphasis on debate and openness. But even if the hard-line trend is now dominant—egged on by the Bush administration’s provocative and threatening maneuvers among Iran’s neighbors and Pentagon covert operations within its borders—journalists should not become sacrificial lambs.

Roxana and other journalists who reside in Tehran were massively hampered by existing in a state that viewed them as official spies. That was barrier enough to considering a freelance career as an intelligence informant. But what Roxana’s case reminds us—aside from the great disservice it did to Iran’s reputation—is that in our increasingly intertwined world journalists are not considered a protected species but treated as fair game.

Iason Athanasiadis, a 2008 Nieman Fellow and a freelance journalist in Iran between 2004 and 2007, wrote this article for The National, published in Abu Dhabi in the United Arab Emirates.