A woman holds her sick child at a mobile U.S. Army health clinic in Nangarhar Province. Photos by Pamela Constable.

Eventually, after the first greetings or the second glass of green tea, the questions would come. I would be in a mosque in Kabul or a villager's home in Khost, huddled on a carpet and taking notes as I struggled to keep my headscarf from slipping and my legs from falling asleep.

The queries from my hosts were always phrased politely. They were asked partly out of kindly concern, partly out of an effort to place a foreign visitor in the known cosmos, and partly out of astonished disbelief. They revealed as much about the questioners — and the gulf between our societies — as the answers did about me.

Where is your husband?

Where are your children?

Are you really traveling alone?

Does your father allow this?

Does your government?

The first few times I bristled defensively, but soon I learned to smile and explain vaguely that my family was in America and that many women from my country traveled alone for their work. I also learned to use these awkward exchanges as an opening to find out more about Afghan culture, especially the restrictions on women, which made my own adaptive discomforts seem like paltry inconveniences.

When the Taliban Ruled

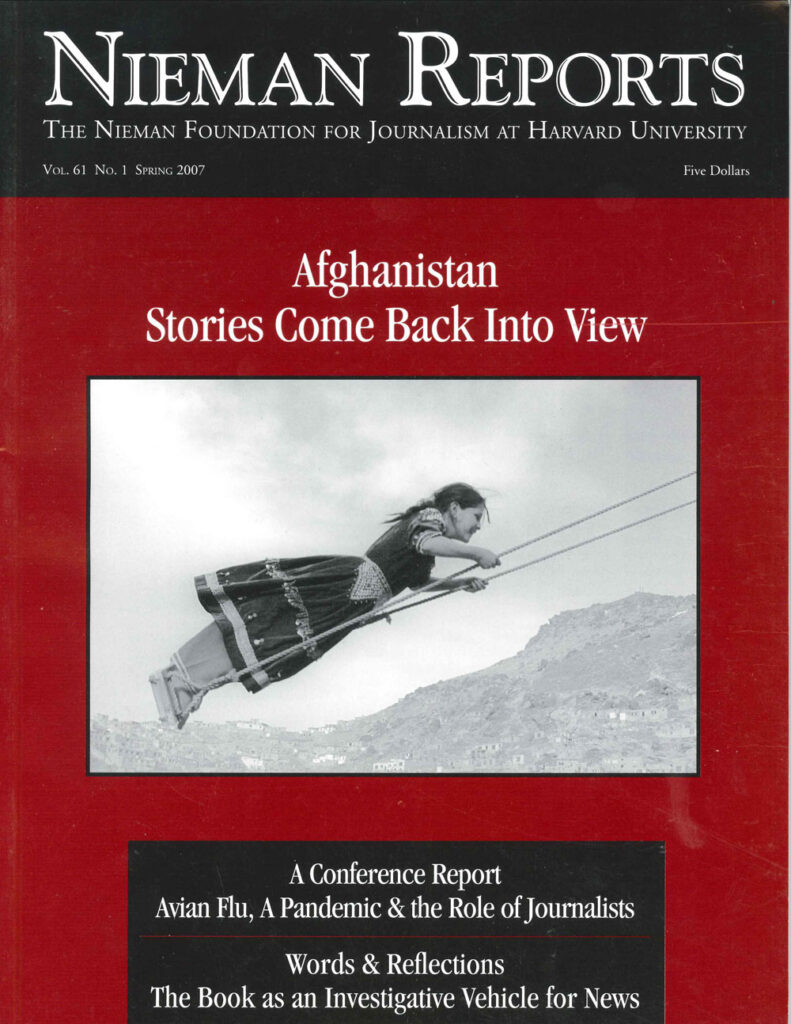

When I first arrived in Kabul in 1998, the Taliban militia was in full control, and women were literally nowhere to be seen. By decree of the Islamic rulers, they were forbidden to attend school or college, to go to a market or hospital without a male relative as escort, or to work except at emergency occupations such as obstetrician or women's prison guard. If they stepped outside their homes at all, they had to don a head-to-toe burka that hid their eyes behind a grill of cotton mesh.

As a female visitor from the West, I represented everything the Taliban abhorred or feared. Except for a handful of UN workers who remained largely confined to their compounds, there were almost no foreign women in the country at all. But since the government wanted to show the world it had brought security, piety and justice to a lawless conflict zone, it admitted journalists like me for brief, controlled visits.

If we happened to be women, the authorities solved that problem by treating us as honorary men. We tried to look and act as sexless as possible, and they, in turn, accorded us privileges normally reserved for men. For example, I was permitted to interview male officials, although some of the more pious Talibs refused to shake my hand or look me in the eye. I was also permitted to conduct "man on the street" surveys, though not to enter private homes or speak with women. Because I am not Muslim, the Taliban did not require that I wear a burka or cover my eyes. But after my first forays into the bazaars — where turbaned militiamen leered and muttered as I passed — I soon retreated beneath a shapeless getup of tunics, shirts and scarves I had scavenged from street vendors.

Once, as an experiment, I attempted to walk through a bazaar in Kandahar City wearing a full burka. The result was laughable, infuriating and unexpectedly liberating. I stumbled repeatedly, unable to see and tripping on the heavy folds of nylon, and yet I was relieved to realize that no one knew or cared who I was. For the first time in half a dozen tense visits to Taliban territory, I hardly drew a glance.

At the time, though, I could neither see nor speak to Afghan women, let alone learn what was in their hearts. The voices of half of Afghan society were silenced, making every brief chance encounter a precious source of information and impressions. I tried to make conversation with nurses and policewomen, passengers huddled in the back seats of taxis and widows baking bread in a UN project. A few words of halting English or Dari, a grimace or a tear before the veil came down, had to substitute for detailed interviews. Sometimes that was enough.

My own frustrations, trivial as they were, also helped me imagine the daily travails of women living in a society whose male rulers were obsessed with protecting the "honor" of women, even at the expense of their health and hygiene. Since women rarely left home and took no part in public life, there were no ladies' rooms to be found except in one or two deserted hotels. On long, hot road trips, crammed into taxis or trucks with male guides or soldiers, I learned to force myself to ask drivers to stop near abandoned ruins so I could relieve myself.

A Kuchi (nomad) woman holds a baby goat inside her tent in eastern Afghanistan. Photos by Pamela Constable.

Afghan Women Emerge

It was not until the Taliban authorities were gone that I finally had a chance to enjoy meaningful conversations with Afghan women, to look into their eyes, and to discover first-hand some things about their lives under strict Islamic rule. With the Taliban gone, I was free to knock on any door, and many Afghans were eager to talk. In the first few months after the regime was ousted in late 2001, I interviewed a teacher who had operated a secret girls' school in her apartment, a villager whose wife had died in childbirth because he was not able to escort her to the hospital, and an engineer's wife who had been beaten by the religious police for washing dishes in her own yard without wearing a head scarf.

But although Afghan women were clearly relieved to be rid of the Taliban's oppressive presence, my Western colleagues and I were astonished to see how little this "liberation" affected their daily lives. We had expected them to toss away their stifling burkas, but many continued wearing them outdoors as if nothing had changed. In the villages, we learned, this was because family and tribal tradition demanded that women be hidden from male eyes. In the cities, it was because women still feared assault by marauding militiamen and were not certain what the new, post-Taliban rules allowed. To women who live in the West, a burka might be a dehumanizing shroud, but to them, it was a comforting cloak of invisibility.

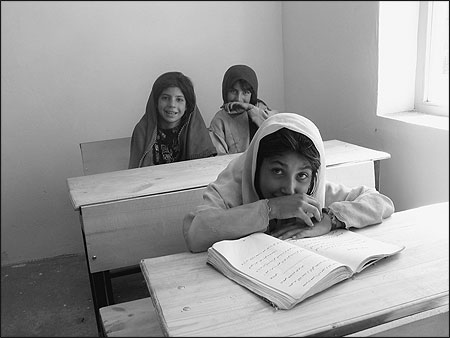

Gradually, under the new, UN-backed government, girls in cities and large towns did begin returning to school and women to jobs. I visited tent-schools erected by UNICEF in villages across the country, where teenaged girls who had been forced to stop studying for years were beginning the third grade and reciting the alphabet alongside tiny classmates. Kabul University, reopened to young women for the first time in a decade, was soon flooded with applicants. In public buildings, women returned to dusty desks as clerks and teachers and secretaries.

Officially, the new Afghanistan embraced women's rights and political participation, with a new constitution that enshrined equality between the sexes, voter registration for all adult citizens, and a substantial portion of seats set aside for women in the new Parliament. During the voter registration drive in 2004, I drove to a number of rural provinces where local elders and officials were devising ingenious ways to secure women's participation without exposing them to male contact. In one village in Khost Province, a high school student was stationed in a farmhouse, where she collected the thumbprints of the illiterate village women, wrote down their names and ages, and then took the new voter cards outside to her uncle, who carried them to a gas station where the men were registering.

For visitors like me, life in Afghanistan became more comfortable and relaxed with each year that Taliban rule receded. By 2004 I could travel anywhere, talk to anyone, and buy anything I wanted, from French wine to Japanese cell phones. I still took care to dress modestly and cover my head, but only out of deference to the culture. People still asked me awkward questions — How many children do you have? Why are you traveling alone? — but I had long since stopped minding the intrusion.

In many ways, however, the lot of women in Afghan society changed very little. The omnipresent blue burkas, billowing so brightly on the streets where women shopped or begged or waited for taxis, reflected the invisible strictures that controlled their lives behind closed doors, where family life was dominated by men, and even the most intimate and permanent decisions affecting a girl's or a woman's life were made by others.

During my years in Kabul, I became friends with a variety of Afghan woman, including teachers and doctors. We had long conversations about life and struggled to understand each other's cultures. All of them willingly submitted to arranged marriages and tried to make them work. Some suffered from abusive fathers or husbands, but they never considered complaining to the authorities because of the shame it would bring on their families. None of them felt strong enough to defy the bonds of duty or the power of gossip that ruled their world.

Outside cities and provincial capitals, it was still often difficult to interview Afghan women. Even though the religious police were no longer lurking about, village and family tradition forbade women from interacting with unrelated or unknown males. Almost no rural women spoke English, and I always traveled with a male translator, so even if a family agreed to an interview with me, at times it had to be conducted literally on two sides of a curtain.

From other sources, including newly formed human rights organizations, stories of terrible abuse and injustice came to light. Young women were sent to prison for fleeing from husbands who beat them. Girls as young as seven were forcibly engaged to elderly men as blood compensation in tribal disputes. Female illiteracy and infant mortality remained appallingly high, at a par with the poorest countries in sub-Saharan Africa.

At a private clinic, I interviewed a village woman who had delivered a stillborn baby after three days in labor at home because she had no way to get to a hospital. In a nonprofit shelter, I interviewed a young woman who had been married at 11, widowed at 12, and forced to work as a servant for her in-laws for the next eight years, until she could no longer stand the beatings and worked up the courage to run away.

Students sit in a classroom in a newly built girls' school in Parwan Province. Photos by Pamela Constable.

The Taliban's Resurgence

Most worrisome of all was the resurgence of the Taliban militia, which began launching attacks in 2005 and soon grew into a serious threat in numerous provinces. Among its goals was to stop the emancipation of women, and its fighters burned schools and threatened teachers across the southern provinces. One of my stories in 2006 was about rural homeschools where girls were learning to read and write in secret — just as they had to do during the Taliban's rule.

Yet Afghanistan was not the same cowed and isolated country it had been just five years before. Now it had the support of 40,000 foreign troops and hundreds of millions of dollars in foreign aid. Now it had an elected civilian government, a constitution that enshrined human rights, and a legislature that included dozens of women. Afghans did not want to overturn their religion or culture, but they did not want to return to the dark times either, now that they had glimpsed the possibilities of progress.

In one guarded village classroom, hastily converted from a front parlor after a nearby school had been attacked by insurgents, a girl of 10 shyly held up a colored drawing of a flower she had copied from the blackboard and offered it to me. The morning sun streamed in a window, and the little blossom seemed to glow in the light.

Pamela Constable is a staff writer for The Washington Post. She has reported frequently from Afghanistan since 1998, and she was the Post's Kabul bureau chief from 2002 to 2004. She is the author of "Fragments of Grace: My Search for Meaning in the Strife of South Asia," published in 2004 by Potomac Books.