April 4, 1983 was the 15th anniversary of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.’s assassination. The day before was a Sunday, and I was with my family in the virtually all-white church we attended in Memphis. I was 11 and naive and a bit self-righteous. I thought that in the very city King was killed, the pastor would surely work King’s death into his sermon, maybe something about Beatitudes — you know, blessed are the peacemakers. He did not, and I was disappointed.

After church, I wrote the pastor a letter. Why would he be silent on a movement and a man who mattered so much? And how did he think that made me feel, as one of few Black congregants at his church? I have no idea where I found a stamp or an envelope, but come Monday, my letter was in the mail.

On Wednesday night, my family was back at church for Bible study. After Bible study was over, the pastor approached me and my mother. He asked us to sit with him in the back of the sanctuary. He said he’d gotten my letter as my mother looked at me as if to say: What letter? He said he’d never meant to offend me, and tears formed in his eyes. He said some other conciliatory things, but I didn’t say anything at all — my letter had said all I wanted to say.

I can see now that this pastor’s failure to mention Dr. King, what could be described as an innocent oversight, was in fact an omission. And omission is erasure.

That’s a large part of why I became a journalist, to make sure that nothing that mattered to people who look like me would be omitted.

By 2008, the 40th anniversary of Dr. King’s assassination, I’d become the first Black woman to be a columnist for Memphis’ daily paper. Often, I wrote about topics that made some readers squirm, or worse. That included a call to remove the city’s Confederate monuments. Those columns made a few white readers angry enough to threaten to kill me.

But after a reader threatened to rape me — a threat that the newspaper’s editor and publisher didn’t seem to take seriously — I knew that I’d have to find another place to do the storytelling that King’s legacy deserved.

And that’s where a germ of an idea formed: To create MLK50: Justice Through Journalism, a nonprofit news project to examine what we’d done with King’s sacrifice.

I took the idea here, to my Nieman fellowship, and held it in my mind during my favorite class: “Poverty in America,” taught by sociologist Matt Desmond. He asked a question that I’ve sat with ever since: What if poverty isn’t an accident, but a robbery?

What if poverty isn’t an accident, but a robbery?

If poverty isn’t an accident, but a robbery, then there are thieves. And the thieves have names. And the thieves’ names should be known.

I returned to Memphis ready to look for people and institutions that steal from the poor. Here’s what I knew for sure: Legacy media was going to frame the 50th anniversary of King’s death as an unqualified celebration of Memphis’ progress since 1968.

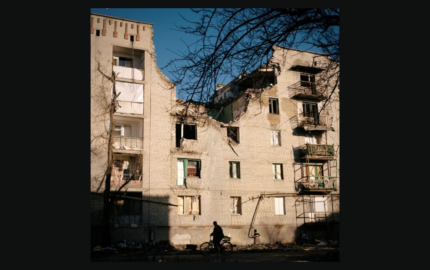

But when I compared the state of Black Memphis in ’68 to the state of Black Memphis in 2018, too little had changed.

The Black-white income gap had barely budged. The Black-white wealth gap had actually grown when accounting for inflation. In 2018, one in four Black Memphians lived below the poverty line and 40 percent of Black workers in the city earned less than $15 an hour.

King’s last trip was to support the city’s striking Black sanitation workers, who were overworked and underpaid. Fifty years after his death, one of those striking workers was still on the job because he couldn’t afford to retire.

On April 4, 2017, I launched MLK50 with $3,000 I’d raised from friends and family. I ran up $38,000 in credit card debt as I slowly raised enough money to pay a small but mighty team of freelancers to write about poverty, power, and policy.

And in 2019, I started an investigation that would expose the thieves and would change more lives than I could have ever dreamed.

The story: The debt collection practices of the area’s largest nonprofit hospital, Methodist.

For decades, Methodist had quietly been suing patients unable to pay their hospital bills, dragging them into court where they were forced to share intimate details of their finances in front of strangers.

Like all nonprofit hospitals, Methodist is required by the IRS to provide free or discounted care to the poor. But Methodist’s policies were exceptionally stingy.

The hospital sued so many people that they owned a collection agency, which added mountains of interest to the patients’ debt. The lawyers got their share, too, and every time another patient was sued, the court collected a filing fee.

Often, the defendants would be wearing Methodist hospital uniforms. Yes, Methodist regularly sued its own employees. Including low-wage workers who couldn’t afford to pay their bills to the very same hospital they worked for. That includes Miss Marilyn, a hospital housekeeper who made $12.25 an hour and owed $23,000.

Another woman I met at court was Miss Carrie. Miss Carrie reminded me of my mother — they are both short and very religious. Neither wear makeup, and both dress very, very modestly.

At the time, Miss Carrie was working at a grocery store, making $9.05 an hour. A surgery left her with a $12,000 bill. Over the years, thanks to interest and attorney’s fees, the debt ballooned to $33,000. $33,000. That’s twice what she earned that year.

And still, a judge ordered her to pay $100 a month. If Miss Carrie paid on time, every month, she’d be 90 years old by the time she paid off her debt.

Most defendants weren’t like Miss Carrie: They didn’t want to talk to me on the record. Debt and shame often travel together.

Armed with court records and defendants’ addresses, I spent my Saturday mornings driving around some of Memphis’ poorest neighborhoods.

I knocked on door after door, tucking my business card and a discreet note into storm doors, under windshield wipers, or handing them to a skeptical resident. No one called me back, and I’m sure most of my business cards landed in the trash.

There were many Saturday mornings that ended in tears. I’d never been so sure I had an important story to tell about women who had been overlooked, omitted, and erased, and I never had a story that was so difficult to report.

But after months of door knocking, I found enough defendants willing to go on the record. In June 2019, with much help from ProPublica, we published the series “Profiting from the Poor.”

The impact was swifter than I could have ever dreamed. It turns out shame can also be a motivator. Methodist pronounced itself “humbled.” Within days, the hospital stopped filing new lawsuits. Then it raised the pay of their lowest-paid workers from $10 to $15 an hour. It made its charity care policy twice as generous.

And then, the hospital erased more than the debt owed by more than 5,300 defendants. The total debt erased was just under $12 million.

That means that thousands of patients will never be sued for hospital bills they can’t afford to pay. And there are hundreds of Methodist employees who have more money in their paychecks, thanks to our investigation.

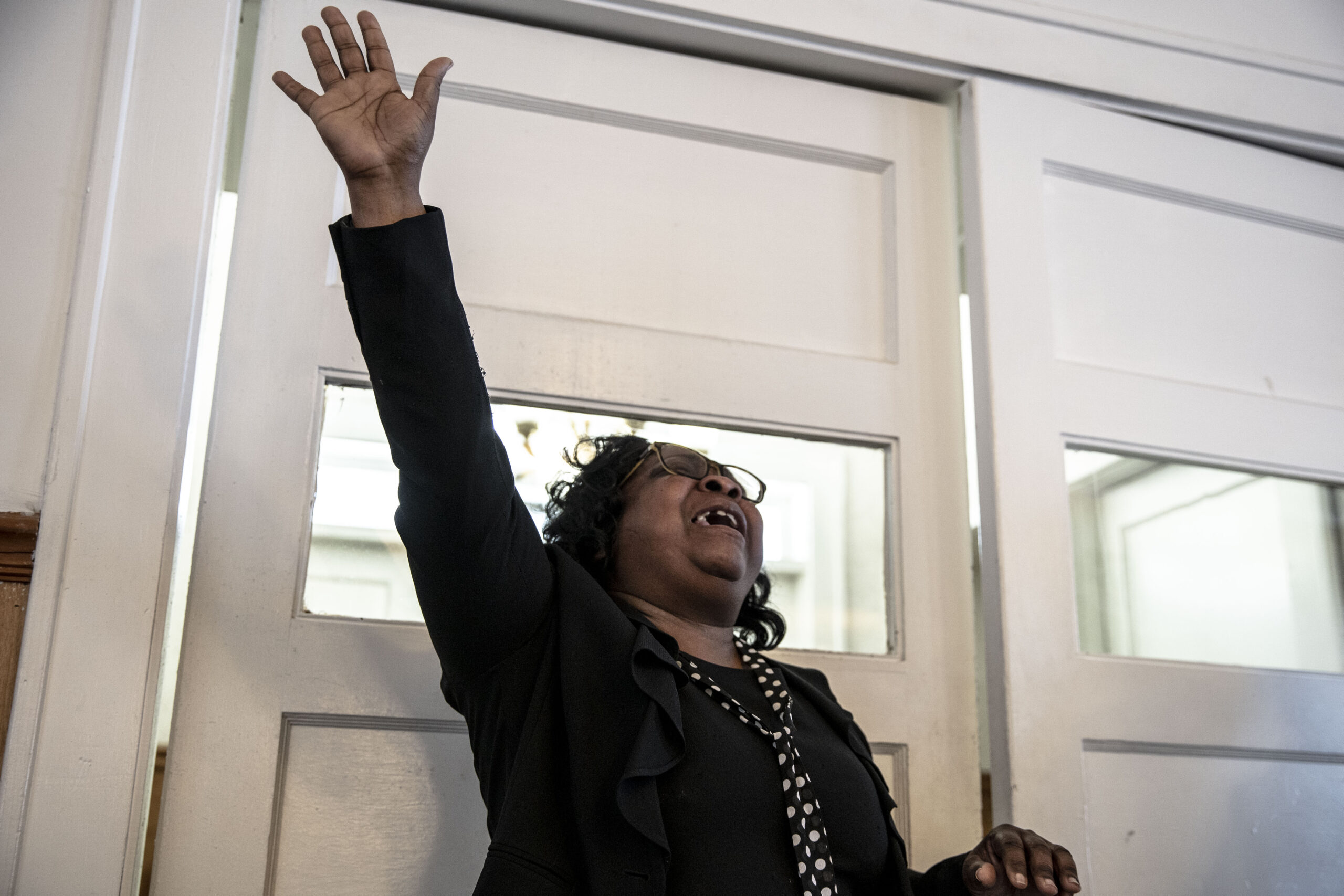

Miss Marilyn, the hospital housekeeper who owed $23,000? She didn’t have a car, so sometimes I’d pick her up and take her home from work. When I saw that the court had erased her debt, I printed the paperwork and called her to see if she needed a ride.

She did. In the car, I handed her the case satisfied notice. Confused, she asked me what it was. I explained that her debt had been erased and she screamed.

“Did we do this, Miss Wendi?”

I told her, “You did this, Miss Marilyn.”