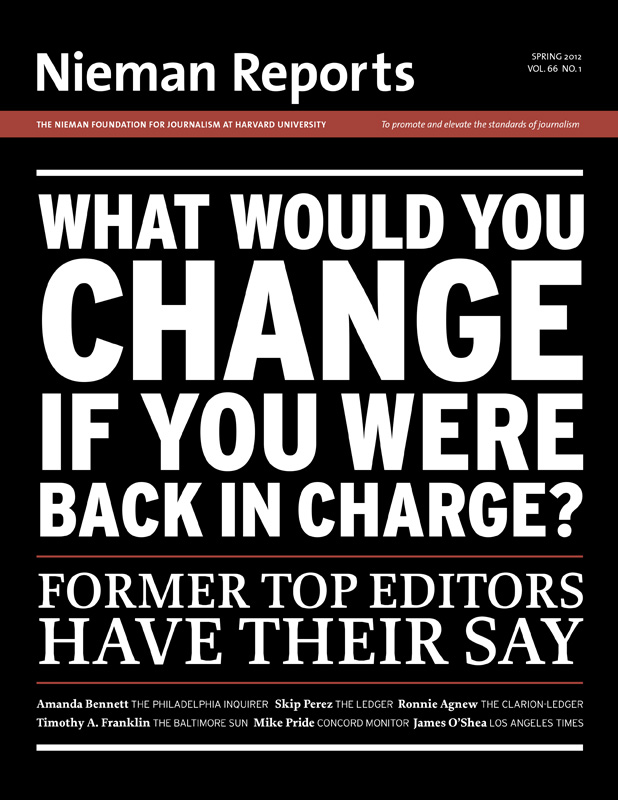

Oakland journalist Chauncey Bailey, right, is blocked by followers of Yusuf Ali Bey as their leader leaves a court hearing in 2002. Photo by Nick Lammers/Oakland Tribune, courtesy of the Bay Area News Group.

Chauncey Bailey died on August 2, 2007, shot as he walked to the Oakland Post, the weekly newspaper he edited in the San Francisco Bay Area. At the

Killing the Messenger:

A Story of Radical Faith, Racism’s Backlash,

and the Assassination of a Journalist

By Thomas Peele

Crown Publishers. 441 pages. time Bailey had been investigating Your Black Muslim Bakery, an Oakland institution led by Yusuf Ali Bey IV, a man with a long criminal history.

When I learned about Bailey's murder, my first thought was "Arizona Project." To his credit, investigative reporter Thomas Peele, much younger than I am, had the same thought.

The Arizona Project was formed in 1976 to send the message that killing a journalist would not kill a story. That year Don Bolles, a reporter at The Arizona Republic, was murdered over an ongoing investigation into organized crime that upset its targets.

Under the leadership of Newsday's Bob Greene, a team of journalists gathered in Arizona to complete Bolles' investigation. Then an investigative reporter at The Des Moines Register, I served as a distant cheerleader for the Arizona Project, which produced a book-length exposé. When I became executive director of Investigative Reporters and Editors (IRE) in 1983, I fielded questions about Bolles and the dangers of investigative journalism, and I answered critics who objected to journalists engaging in a crusade.

In the weeks following Bailey's murder, the Chauncey Bailey Project came together quickly. Peele moved from the Contra Costa Times to the Oakland office of his employer, the Bay Area News Group, which also published the Oakland Tribune and the San Jose Mercury News. Other participants included currently employed and retired journalists from other newspapers, radio, television and nonprofit organizations; freelance journalists; and journalism students and professors from two universities.

Peele, the lead information gatherer, and his fellow investigators were uncertain whether they could find justice for their colleague. But they knew they could send a message: "Killing a reporter would result in far more journalistic scrutiny than a single reporter could have achieved," as Peele writes in his new book, "Killing the Messenger: A Story of Radical Faith, Racism's Backlash, and the Assassination of a Journalist."

His book is a welcome development for journalists everywhere who want to know how the investigation unfolded, but never found time to follow the daily breaks. Much of it is devoted to an impressive history of the Nation of Islam (also known as the Black Muslim) movement, but I will focus on the journalism that got Bailey killed and the journalism of Peele's team—journalism meant to advance Bailey's suspicions about Your Black Muslim Bakery and its criminally minded brain trust. Any journalism emerging that helped identify and punish Bailey's killers would count as a bonus.

The crew behind Your Black Muslim Bakery had threatened at least one journalist before Bailey. As Peele recounts, "a gutsy reporter named Chris Thompson of the weekly East Bay Express had written several long exposés about the Beys [the family that dominated the Black Muslims]. Consequently, he received death threats, the windows of the Express's office were smashed, and Thompson spent several weeks in hiding."

Police raided the Beys' North Oakland compound the day after Bailey's murder; soon a confession emerged. Devaughndre Broussard, a 19-year-old Bey soldier, "admitted to police he had killed Bailey to stop a story he was writing about the bakery and [Yusuf Ali] Bey IV." Bey IV was 21 years old at the time, with lots of influence derived from his deceased father, the original Yusuf Ali Bey, a made-up name.

Bailey's Shortcomings

With candor aplenty, Peele writes in the introduction to his book, "It didn't matter that the Post was a small weekly on the margins of journalistic credibility or that Bailey was, at 57 years old, caught in a downward career spiral. What had happened to him was far bigger than that. The free press on which the public depends to keep it informed had been attacked." Bailey was an African American who had overcome racism in his personal and professional lives. The Post circulated free, almost entirely among an African-American readership.

Bailey graduated from journalism school at San Jose State University in 1972. His career began at a San Jose television station and continued at an African-American newspaper in San Francisco. He eventually moved to reporting jobs for the Hartford Courant and The Detroit News. Back in the Bay Area in the early 1990's, Bailey began covering African-American doings for the Oakland Tribune, sometimes writing positive stories about the Bey family empire built around the bakery, which served simultaneously as a compassionate employer of ex-convicts, a community center, a mosque, and a command post for thuggery.

Peele praises Bailey's deadline reporting skill, his tireless work ethic, and his passion for newspapering. Yet despite helping avenge Bailey's murder, Peele is unsparing about Bailey's superficial and sometimes boosterish journalism at the Oakland Tribune during the 1990's and into the new century. Bey had run for mayor of Oakland in 1994, opening himself to scrutiny. Yet his involvement in multiple murders, rapes, public assistance fraud, child labor law violations, and other illegalities was not widely known.

Here is a sample passage from Peele: "Yes, Bey was a racist, an anti-Semite; he went on television every week and said some crazy things. But Bailey was of a generation of African Americans who were cautious about judging one another … Of course, Bailey didn't know that Bey was far more sinister than he even seemed … If Bailey did suspect anything, he wasn't going to spend weeks and months digging it up. … There were welfare records, police reports, court documents. Together, they could have been used to assemble the puzzle that was Yusuf Bey."

When Bey died in 2003, Bailey wrote the obituary for the Tribune. It did not completely ignore Bey's crimes, but, according to Peele, it was too deferential. In any case, Bey's offspring continued operating the bakery and the associated criminal enterprises. Meanwhile, the Tribune fired Bailey during 2005 for unethical professional behavior. Bailey pieced together a freelance journalism career of sorts, one that brought him into contact with the Bey enterprises.

Bailey wasn't alone in stepping lightly around the Bey family. Members of the Chauncey Bailey Project calculated they would not receive all that much help from the authorities. According to Peele, the Bey family and its pseudo-religious enterprises "had largely gone without scrutiny for decades," other than Chris Thompson's digging and Bailey's questioning. "The Oakland Police Department's indifference to—or outright fear of—the cult members was legendary. Politicians kowtowed to them, praised them, loaned them taxpayer money that went unrepaid. Even when the cult's patriarch, Bey IV's father, Yusuf Ali Bey, was found through DNA evidence to have raped girls as young as 13 years old, he was still heralded as a community leader. That he died in 2003 before the charges were proven in court only added to his followers' belief that he was a victim of persecution."

Almost a year after the murder, journalists from the Chauncey Bailey Project obtained the secretly recorded police video of Bey IV "laughing about and mocking Bailey's murder." The journalists posted the video, which raised a question about why law enforcement authorities had not held Bey accountable for ordering the murder. The journalists followed up with additional stories about law enforcement's inadequacies.

Peele chronicles high points from the Chauncey Bailey Project's stream of stories. One story explained that "data from the tracking device hidden [by police] on [Bey] Fourth's car showed it [had] been parked outside Bailey's apartment less than seven hours before the murder." Peele also acknowledges advances in the murder investigation published in the San Francisco Chronicle and elsewhere.

Just last year a jury convicted Bey IV of ordering the Bailey murder and other murders. He received a prison term of life without parole.

Steve Weinberg is the author of eight nonfiction books and a freelance writer for magazines.