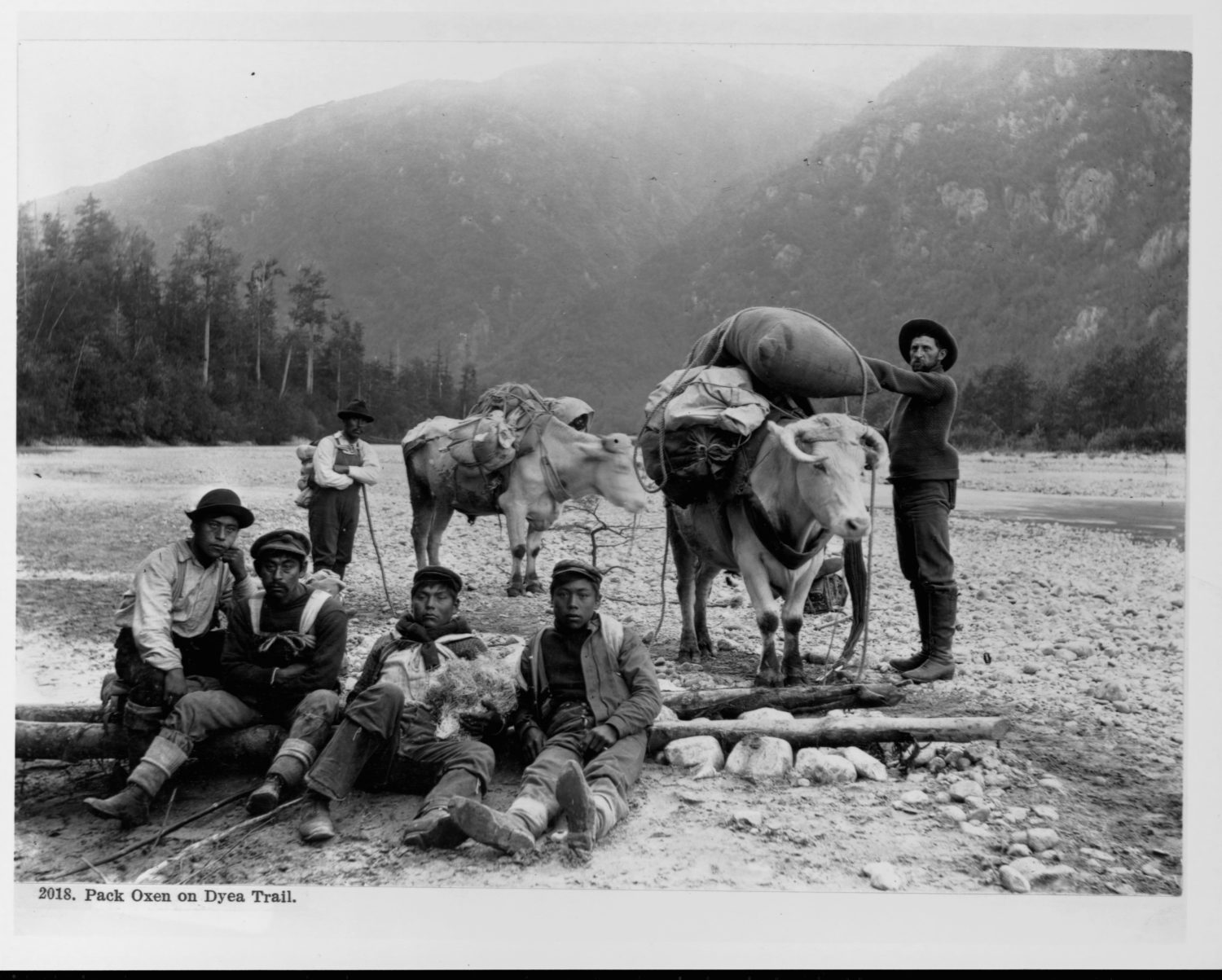

The fever for gold caused the Lakota people’s loss of the Sacred Black Hills of South Dakota as well as the near destruction of the indigenous peoples of South and Central America and California. In Alaska during the gold rush of 1897, prospectors flooded into the state, killing any indigenous person who got in their way.

This is not taught in history books because it shows an extremely ugly side of America that historians choose to ignore.

To learn my own history as a Native American, I turned to the books of the great Cahuilla Indian newspaper editor and author Rupert Costo, my mentor and friend. “The Missions of California: A Legacy of Genocide,” co-written by him and Jeannette Costo, made me understand more deeply that we, the Indian People, had to write our own books in order to bring out the parts of history that were suppressed.

The book gained little recognition because it was about a topic most Americans do not want to hear about. America wants only to show its good side to the rest of the world. But I suggest that you read “The Missions of California” and Costo’s “Indian Treaties: Two Centuries of Dishonor” to more clearly understand the history of the indigenous peoples of the Western Hemisphere. I am a journalist today seeking truth and justice because of Rupert Costo.

The Missions of California: A Legacy of Genocide

By Rupert Costo and Jeannette Costo

Indian Historian Press, 1978

Excerpt

For two hundred years the native people of California have borne the stigma of “Mission Indians.” The names of their nations and tribes are Hupa, Kumeyaay, Cahuilla, Pauma, Malki, Cupa, or Pamó, to name a few.

But with the advent of the Spanish invasion and the introduction of the mission system, these tribes were ignored at the least, and obliterated as tribes at the most. Thus, the outer habiliments of the hated mission system remained into Mexican terminology, and today exists even in the literature and legal references in American terminology.

The architect of the mission system was Fr. Junipero Serra, who has become a symbol of 18th century feudal forced labor and abuse to the Indians, and a symbol of successful foreign domination to the establishment society.

In order to install Serra as a valid, respectable holy man of the most humane objectives and conduct in his life, the Roman Catholic Church has been engaged in a project seeking to have him declared a saint

Used by permission of Special Collections & University Archives, University of California, Riverside.