I was born in a country that was first to have television in Sub-Saharan Africa, but today it is the only African country with just one television station, which is owned by the state and run by an Orwellian-type Ministry of Truth, dubbed the Ministry of Information and Publicity.

The Zimbabwean liberation struggle against colonial rule was meant to put an end to the suppression of freedom of speech and access to a variety of sources of information amongst many other freedoms, but we are still where we were during the colonial rule if not worse. Our freedoms have been constrained and repressed by the only post-colonial ruling political party, ZANUPF, which uses the state security machinery and violence to exert its power.

This has made it particularly difficult for journalists as the country’s Ministry of Information has to accredit journalists — by operation of a draconian law — before they can do any work in Zimbabwe.

In reality, it is the dreaded secret service of Zimbabwe that gives the nod or rejects your accreditation application behind the scenes.

Exactly 20 years ago, I went back to Zimbabwe after being away for nine years living in Britain where I was studying and working.

I came back to Zimbabwe hoping that I would be able to practice as a journalist. However, the head of the accreditation media board who had been my history lecturer at journalism school, Dr. Tafataona Mahoso, told me that he was instructed not to accredit me.

It was extremely surreal that the man who had taught me at journalism college was now the same man standing in my way to stop me practicing the craft that he had taught me a decade before.

He couldn’t look me in the eye; he was extremely embarrassed. It was a short meeting and I left feeling disappointed with how someone like him could easily be bought by the regime to become its media hangman.

The regime asked me to do my journalistic work with the BBC under a pro-government broadcasting television production company in exchange for accreditation. I refused to do so because it would have been self-censorship.

Stuck in Harare, jobless and targeted by my own government simply because I was going to be working with the BBC, which the government considered banned, I applied for a scholarship to study film in London and left the country.

On my return to Zimbabwe in 2007, the political environment had gotten worse. The highly popular opposition party was being hunted down by the regime using state institutions. Zimbabwe now has the highest inflation rate in the world. Shops were empty as the country prepared for another election pencilled for March 2008.

I joined a South African television news channel, eNCA, as its Zimbabwe reporter based in Harare in February 2008.

The election was on March 29, 2008. Robert Mugabe and his party lost the election but refused to go.

They turned to their default political setting of using brutal violence while refusing to release the presidential result for over one month.

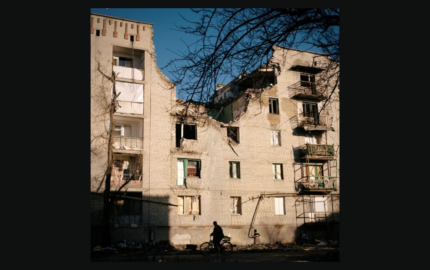

The violence witnessed that month was followed by another two months of non stop indiscriminate brutality. Houses were burned down, and opposition supporters were maimed or killed daily.

I became the first locally based journalist to break the violence story internationally, and for that I was targeted by Mugabe’s regime, which had also refused to accredit me to cover the original election calling me a national security risk.

That is a euphemism for being declared an enemy of the regime.

I always watched my back as I went into communities filming. It was tough because television news requires cameras, tripods, and at times, big microphones to record events.

There was no stable or fast internet at that time, so we used satellite phones to file stories to London or Johannesburg. If caught with one, you risked going to jail.

The election period had been so traumatic for most journalists who covered the violence in-depth. It was painful watching people having their homes burnt to the ground, their limbs and hands cut off, or villagers killed in the senseless violence.

It was scary to film in rural Zimbabwe because that was the hotbed of Mugabe’s shock troopers who could maim or kill with no consequence to them.

Nine years later, in 2017, Robert Mugabe fired his vice president and long-time enforcer, Emmerson Mnangagwa, who immediately ran away to South Africa fearing arrest, only to come back three weeks later after a military coup as the new president.

Mnangagwa started off by making all manner of fairy-tale political promises, but it became clearer that it was only change in name and not deeds as his administration became the source of massive looting of public funds and rampant corruption. Public funds were being routinely looted without consequence, and audit reports were ignored without exception.

I started speaking out about it through social media. I also started investigating and exposing the rampant corruption that was taking place, and the more I did that, the more state actors and ruling party senior officials attacked me publicly both on social media and through the state-controlled media.

The pandemic began in 2020, and a Covid-19 fund of $60 million was set up to help fight the pandemic in Zimbabwe. I uncovered that it was being ruthlessly looted by powerful political elites. They were raising prices for a $.65 mask, selling them to the state for $30 a piece. They formed shell companies both at home and abroad using their children, relatives, and friends to bid for state tenders, which were awarded without transparency.

I spent one month reporting about it every day because each day my investigations discovered new things.

I used social media platforms to report, mainly X, Facebook, and Instagram which reached younger audiences using videos that I recorded speaking into a camera phone.

My investigations led me to the highest levels of government.

The excitement and disbelief that my social media reports caused were palpable and national. My reporting raised unmatched levels of public anger, but that anger made the regime angrier at me.

Then on July 20, 2020, the dreaded knock was heard on my gate.

The police were let into my compound by my staff. I locked myself inside my home waiting for my lawyers to arrive. Instead of waiting for my lawyers to arrive, the police, who had secret service details with AK47s, hit my dining room door glass and walked into my home, all seven of them.

As they came toward my bedroom, I picked up my cell phone and started a live broadcast on Facebook. I filmed them coming into my bedroom, but they ordered me to put the phone down and I complied because they had guns. But the film had already gone out to the world and global news networks were broadcasting it within an hour of being filmed.

I was dragged out of my home, walking on top of broken glass barefoot. I spent two days and nights at the police station. The regime didn’t know what to charge me with or which law to use because the arrest was bogus and political.

They took me back home twice to search my property. They took all my computers, cell phones and camera equipment.

I was eventually charged with tweeting against corruption, and the charge ridiculously said that the tweets would lead to the removal of the government.

I was denied bail three times and taken to Africa’s worst prison, Chikurubi.

As the truck drove me to the prison from the magistrate’s court, I felt the pain of being persecuted for simply doing my work.

I spent 45 days in Chikurubi, staying amongst murderers and rapists without clean running water and sleeping with 45 convicts in a cell meant for 14 people, only because I was practising journalism and had exposed corruption.

I fell sick while in prison with Covid-19 and was denied access to proper medical care. The prison hospital was just as bad as all Zimbabwean public hospitals, with no medication or basic equipment.

I spent my time speaking to prisoners who saw me as a hero of some sort and protected me from unsavoury criminal characters. Most of the prison officers were kind to me and took turns to tell me how they were suffering living on paltry salaries.

I realized that I was building a story from these anecdotes, one which I told when I left the prison. Instead of being depressed, the journalist in me started taking notes which turned into stories about the prison conditions.

I was released from prison in September after my fourth attempt to get bail.

Three weeks after my release from prison, the president’s niece was caught trying to smuggle six kilograms of Gold to Dubai on a scheduled flight. A plan was hatched to give her bail unopposed, an insider informed me, and I exposed it using my X handle.

I was arrested again six days later and charged with another bogus charge of interfering with a pending case before the courts. But there was no pending case before the courts — it was just another excuse to punish me for exposing the corrupt arrangement to give bail to the president’s niece.

I was jailed for 23 days and only released by the High Court of Zimbabwe — the magistrate courts are completely captured by the regime, so you stand no chance of getting bail there for political persecution charges.

I was arrested again on January 8, 2021, for something that I didn’t do using a law that doesn’t exist. I was jailed for 24 days and again only released by the High Court on appeal. Every time I was imprisoned, I was sent to Chikurubi maximum prison where only convicted prisoners are sent. This was meant to punish me.

However, my work and the political persecution have not been in vain. The exposures of corruption were acknowledged internationally and managed to put a spotlight on Zimbabwe’s failed governance.

When things get tougher with arrests and imprisonment, one has to be creative to reach young people about corruption.

I recently did a music skit which I called “Dem Loot,” which means “They Loot.”

The anti-corruption message was delivered with fun, but effectively. It went viral and the government was even more upset, but they couldn’t arrest me for singing.