A Colombian “Jungle Command” police trooper is surrounded by children in Meta province. Thousands of children work in the coca business, mostly as “raspachin,” coca leaf harvesters. Photo by Steve Salisbury.©

It’s still the stuff of cocktail party snickering among the correspondents in Bogotá: Tod Robberson, his wife and daughter once spent part of an evening cowering on their kitchen floor because someone outside their apartment kept “painting” their heads with a laser.

At the time—two and a half years ago—we thought a sniper was training his gun sight on us. It turned out to be two teenagers playing with a toy laser pointer. Everyone laughs about it now, but the situation was dead serious at the time. In fact, so serious that my wife later told me: “I want out.” My editors agreed that it was time to reconsider our presence there, in spite of how it might impact our coverage.

Colombia is unquestionably the hottest story in South America right now, and newspaper editors are pushing their correspondents to milk the story for everything it’s got. The United States is pumping $1.5 billion in mostly military aid into Colombia and surrounding nations, while Colombia’s military, guerrillas and paramilitaries are gearing up for a period of potentially unprecedented bloodshed in the months to come.

The Dallas Morning News, Houston Chronicle, and Miami Herald all are maintaining some form of permanent presence in Colombia. The news hole and appetite their editors have for Colombian stories seems unlimited. The Washington Post, The New York Times and Los Angeles Times decided late last year to open bureaus or satellite bureaus in Bogotá. Two of those newspapers consulted me before deciding exactly how they wanted to handle the dangers posed by Colombia, apparently because word about my experiences had made the rounds.

The issue that concerns all of us, primarily, is one of safety and how it affects a correspondent’s ability to cover the Colombian story. We constantly find ourselves balancing our drive to cover an exciting news story against our overriding desire to stay alive and kidnap-free in a country infamous as the kidnapping capital of the world. My solution was to move my family to the safer climes of Panama, but to keep an assistant and small apartment in Bogotá. I can “commute” to my job.

Let’s backtrack a bit to see why such a drastic move became necessary after the laser pointer incident. Around the time we found ourselves crawling across the kitchen floor, the nation’s largest rebel group, the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia (FARC), was staging its biggest-yet offensive. On the advice of the U.S. Embassy, American businessmen in my Bogotá neighborhood were barring their apartment doors and staying away from work because of intelligence about a large-scale kidnapping being planned by the guerrillas. The rest of the foreign press corps had not been told of the embassy alert, and the only reason I knew was because some friends at the embassy had passed the warning along privately. We already were nervous.

Also around that time we were picked up one morning by a taxi driver who offered—without being asked—to recite all the details he and his colleagues had been collecting about our daughter. The driver knew her name, her address, where and when she went to school, and the hour she normally returned home. Was someone profiling her so that the information could be sold to kidnappers?

That incident was followed by a series of crank phone calls over several weeks. There was always a silent pause, after which the caller would hang up without saying a word. Then the phone quickly would ring again and again.

But one day, after the long succession of hang-ups, the caller decided to stay on the line. I could hear him take the receiver away from his ear, as if aiming it elsewhere in the room. There was the distinct sound of a little girl crying in the background. In a panic, I called my daughter’s school to make sure she was safe. She was, but the terror I felt didn’t subside for weeks.

Against that backdrop, it’s easy to see why my wife wanted out, and why other correspondents in Colombia are now talking about leaving as well. We are all under a tremendous amount of pressure from our families, friends and editors to modify our coverage of Colombia for the sake of our personal safety, even while we are pressuring ourselves to get more deeply involved in coverage of the Colombian war. It’s in our blood, or we wouldn’t be here in the first place.

So we tend to follow the time-honored rules. We never travel alone, we always inform colleagues about our travel plans. If it’s a particularly risky trip, we fix phone call deadlines. If I haven’t called my wife or my desk by a certain time, they have a “panic button” procedure they can follow to locate me and make sure I’m all right. If that doesn’t work, other procedures are supposed to kick into action.

When I arrived in Colombia four years ago, it was unlike any other war zone I had worked in. I’ve covered at least five major conflicts, including Lebanon, the Iran-Iraq war, and El Salvador. But Colombia was the first place where I could not pass among the different warring parties with a relative assurance that they would not do me harm. In fact, until recently, the FARC and the paramilitary militias gave every indication that they would not hesitate to kidnap or kill anyone who approached them without going through proper channels. And they never quite spelled out what those proper channels were. The risks seemed too high, and many of us tended to avoid venturing into certain parts of the countryside, even as a group. Our coverage and balance suffered as a result.

Much has changed in today’s Colombia, largely due to the increased U.S. presence there and the competition among the Colombian government, the guerrillas, and the paramilitaries to influence our coverage. All these players have set up their own, well-oiled press operations. Thanks to a Switzerland-sized safe haven created for the FARC in southern Colombia, we journalists now can fly straight into the rebel heartland. Within minutes of landing, we can be sipping beer or shopping for kung fu videos with a top FARC commander. Not to be outdone, the paramilitaries have opened channels so that their leaders can be interviewed more easily in the field. In December, I actually received an e-mailed New Year’s greeting from the FARC. With only one or two phone calls or e-mail messages, we can arrange interviews with just about any player in the Colombian conflict.

More importantly, the foreign press corps seems to have been granted the same kind of diplomatic immunity that allowed us to move relatively freely in other war zones such as Lebanon or El Salvador. It means we can cover Colombia much more thoroughly than before. We can ask tough questions of paramilitary and guerrilla leaders without being worried that they will retaliate against us.

Still, we cannot forget that we are dealing with a nation held hostage by thuggish gunmen whose rules of engagement seem to be changing on a daily basis. There are cowboys among the foreign correspondents in Colombia who love to make fun of me for being overcautious about security. All I can do is remind them of a conversation I had with Terry Anderson back in 1985. Terry spent the better part of a dinner in Amman, Jordan, chiding me about my fears of returning to Lebanon after I had been involved in a hair-raising kidnapping incident. He insisted that journalists had nothing to worry about, provided we maintained good contacts with the major militias and were balanced in our coverage. Two days after that conversation, Terry was kidnapped in Beirut and spent the following 2,454 days as a hostage.

The rules changed in Lebanon without anyone telling us. They might be changing in Colombia, too. As in Lebanon, when the U.S. aid starts flooding in and the bullets start flying thicker and faster, Colombians are going to get angry. They’re going to look for ways to vent their frustrations over U.S. policy. They’re probably going to look for Americans whose abductions might draw some attention to the Colombian plight, and when they can’t find the prominent executives and businessmen they’re looking for, they just might settle for the most accessible Americans they can find: journalists.

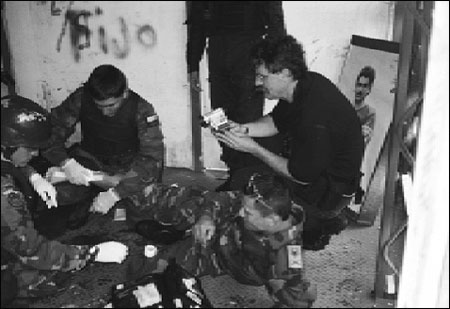

Robert Young Pelton, a TV producer and host, videotapes a Colombian Army special forces sergeant who was wounded by the explosion of a stun grenade during a training exercise. Photo by Steve Salisbury.©

For the past four years, Tod Robberson has been the Latin America bureau chief of The Dallas Morning News, based in Panama City and Bogotá. He also was Mexico bureau chief of The Washington Post, El Salvador bureau chief and Middle East correspondent for Reuters.