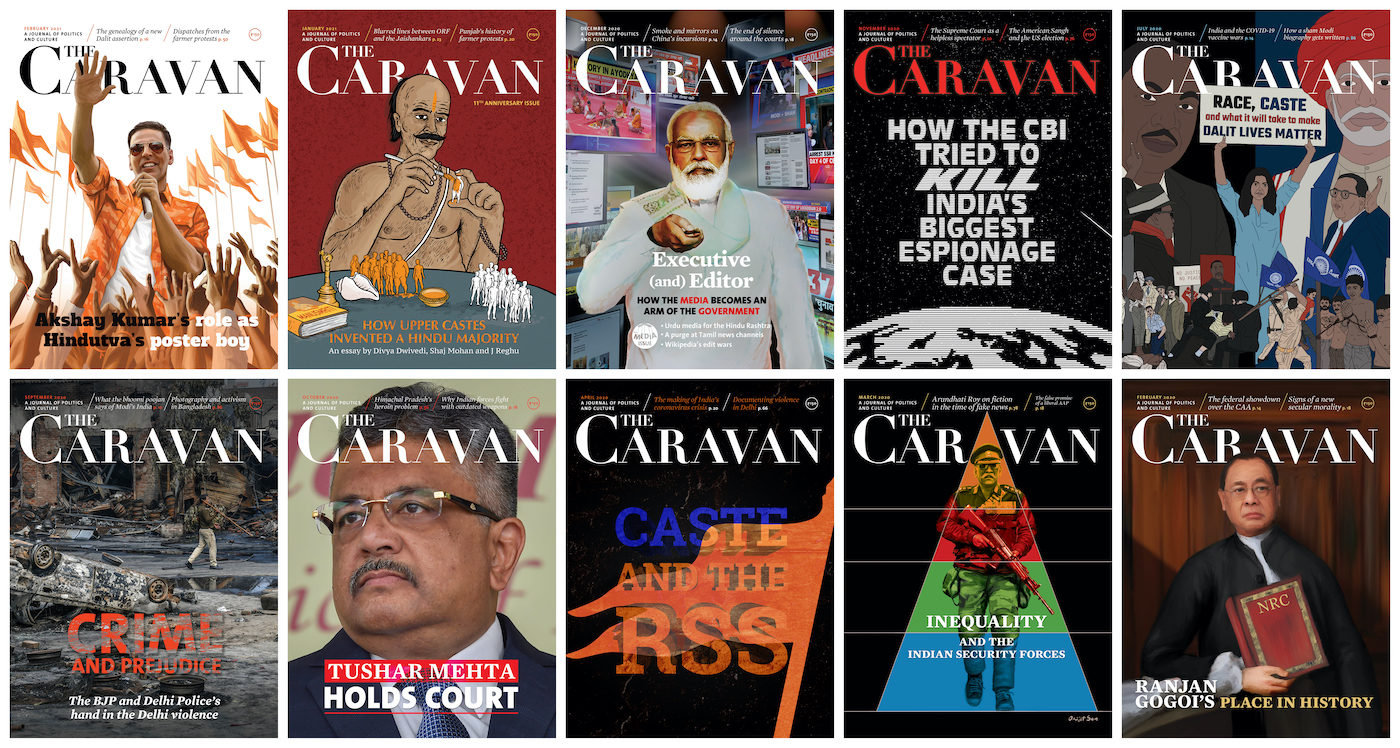

In February, Nieman Fellows at Harvard presented the Louis M. Lyons Award for Conscience and Integrity in Journalism to The Caravan, a New Delhi-based magazine, in recognition of its reporting on the erosion of human rights, social justice, and democracy in India. Coverage by the outlet has included work on violence against Muslims and other minorities, the massive farmers’ protests against policies supported by Prime Minister Narendra Modi and his Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) government, and the Covid-19 pandemic that has ravaged the nation. The outlet has faced growing pressure from the government and its supporters — both online and person — including threats and violence against its reporters.

Caravan’s executive editor Vinod Jose and political editor Hartosh Singh Bal spoke to the Nieman Foundation in May about the political and social effects of the Covid-19 crisis, holding power to account, keeping employees safe from threats, and more. Excerpts edited for length and clarity:

On Covid-19’s impact on Caravan’s newsroom

Vinod Jose: Before the country went into lockdown, Caravan, which has a small newsroom, decided to work from home. We have a print magazine, a web operation, also a Hindi department, and a multimedia one. All of us work in the same flow. We had to take care to prevent that becoming a zone where the virus comes in and takes over the newsroom.[During] the first wave, we were pretty much OK. In the second wave, many of our colleagues have fallen ill. One of them got hospitalized and was on oxygen support, but she’s back. Most of her colleagues are doing all right now. Some of our colleagues lost their lives. Many of our friends or immediate family members have also died.

That’s part of being in India and in very difficult cities like Delhi. It’s across India. Even the states that are able to control it are losing very badly. It’s not very safe. But also the vaccination drive — suddenly, the states are procuring it.

All of us complain that we end up working for more hours and we don’t have a sense of time anymore. Our output has certainly increased. The impact of the stories also has certainly increased, so the energies, so to speak, are certainly at an all‑time high.

Hartosh Singh Bal: Running from remote is the least of our problems. We run a very tight team — everybody contributes in equal measure.

It’s just Covid, the impact of that. The problems of living alone, managing alone, isolation, people whose friends and relatives have been through the situation — the whole mental health aspect of it. In many ways, it’s the kind of pressure none of us have ever faced before. That goes for the entire team.

On resisting intimidation

Jose: When you are a journalist in a country like India, you have two choices. One, when you know that there are political powers and corporate powers who want to censor stories and don’t want a set of stories to come out, you can oblige their requests or demands or threats. Then run a show, be part of an operation, and go back home with your assured salary. That’s one choice.

The other end would be to do what you think is the right thing, which is to report it as thoroughly as you can and put it through the editorial process and then publish it and face the consequences. The word gets out whenever you follow a powerful interest. We often have faced intimidation long before stories have come out. I remember in 2013, a corporation, which was pretty close to the government then, sent us three legal notices back to back while we were editing the story. The kind of pressure that would come even before a story is out is enormous, because often these threats come with multimillion-dollar lawsuits. Often a small publication like us will be worried whether we will be run out of business, whether they will send us to jail, things like that.

When you take a decision on the latter route, you are going to stand by and publish the story because: A) You believe in the story. B) That’s the right thing to do in a democracy, and at that point in time you proceed.

Early this year, some of us were booked on sedition. For example, there are 10 cases against me and the publishers and owners of Caravan. We’ll follow up a story like the farmers’ protests, which has been one of the largest protests that India has seen and the longest by many counts. It’s still continuing. You get booked, not in one case, one state. You get booked in 10 different cases in five states, where the administration is, and the police report directly to Prime Minister Modi. There are messages which we are getting in the process.

Most of the big stories that The Caravan has published, even stories like the Rafale defense scam, most of those stories were brought to legacy organizations, and they did not publish them. They chose not to publish. If you’re an editor and running a publication, you often know how the story comes, who the source is, and how it got from hand A to B to C. In Caravan, of course, the editors need to know the sources. Often, we know what trajectory some information or a file would have taken. We realize that these are stories which made the rounds, [had] gone elsewhere, and other editors chose not to publish.

There is a certain growth which has come because those stories were landing upon our desk, and we are like, “What do we do, except to publish those?” When we published them, of course, that gave us a lot of attention, right and wrong. It also got us a lot of reach. Our subscription base grew. Our Hindi publication is also reaching a large number of people. Multimedia again is growing.

On funding news media

Jose: A couple of things have to come together to have a sustainable media operation in a country like India. I don’t think it can be [based] entirely on a foundation charity route, because the foundations also will come under pressure. We have seen that in a country like India, the philanthropic space is probably not as evolved and doesn’t have that long history of standing up against the government. The new money which has come from the IT industry, the computer software millionaires and billionaires — [they ] are increasingly coming under pressure. That was the hope that we had, that maybe the new money would stand up, but I don’t think that’s generating a sustainable model either.

Having said that, at Caravan, we were extremely lucky to have a publishing family which has been around for over 70 years. The founder of which was inspired by Gandhi. This is now the third generation who is handling the face of the magazine. There’s a lot of freedom and space that that publishing house gives. Compared to many other publishing houses, it’s a silver lining.

We also realized halfway through that we would need to step in and do something else, because otherwise, in terms of resources, it would be a small, independent publishing house where the scope of growth would be limited. We started approaching different foundations. We developed a very robust subscription mode — making the paywalls, conceiving the campaign, constantly asking for money, and things like that.

If you ask me, I think it’s a combination of things which has worked for Caravan. One, the support of what we can call a very rare player in the mainstream legacy space, which is not a megamillion-dollar corporation, but a small independent house which gives it shelter.

Second, a subscription campaign, basically putting the readers at the forefront of the business model. Primarily, it’s people who we will need to prioritize at the center of any news operation. This is so integral to the idea of democracy. The moment our accountability and allegiance move away from people, we lose something as journalists.

On social media platforms in India and the U.S.

Jose: There was a story on the BJP, about the ruling party’s president’s son, Jay Shah. His father (Amit Shah) has been the right‑hand man for Prime Minister Modi for 20, 30 years now. The son’s company and its growth [was] a web story, but the moment we posted it on Facebook, they brought it down. That’s when we first found out that things were not all right. Five or 10 years ago, there were workshops by these social media companies for media and journalists [saying]: “Look, make use of our platform. We are distribution networks. You will get to reach more people.” All of us remember that pitch 10 years ago. Facebook and Twitter were using us and growing.

Now, when the advertisement models evolve, they realize that it’s not journalists who will support them, but the bigger advertisers. BJP, the ruling party, is India’s largest advertiser for Facebook. Also, these are very powerful people. Nobody takes issue with them. They didn’t allow us to publicize the story on Facebook. We wrote to them. The reporter was made to call the Facebook India team. He was getting stonewalled. Then we told him to contact Facebook America, the headquarters. It took 10 days for them to allow us to post that report on Facebook to promote it.

Twitter is far too small compared to Facebook in India. For us to watch Twitter taking down Caravan’s account, after four years, even though it was for just half a day… We have lots of followers, and without even an intimation. No notification. This is against the stated policy of Twitter. They should [have] let us know that this happened, and they didn’t do that.

Finally, wisdom prevailed from the U.S. headquarters. We’ve seen, in the last two months after the Caravan issue, that they’re bringing down accounts of individuals, or people who are very vocal, and opinion leaders, so to speak, in social media. This is widespread. There is something serious going on. I don’t know whether this is an advertising model, whether it’s political intimidation or whatnot, but we certainly see a different value system when it comes to some of the American social media companies, when it comes to a country like India. They were standing up to Trump. Here, they’re certainly behaving in a way that is uncharitable and will place them on the wrong side in history in the years to come, in India’s history and in the social media company’s history. These episodes will tame them in a way that they will be embarrassed when things don’t change around.

On the effects of the farmers’ protests and Covid-19 on the Modi government

Bal: It’s difficult to say what the impact will be, but what is clear right now is that for the first time, Modi and the government have been subject to mass scrutiny and questioning in a way not seen before. Institutionally, a lot of Indian democracy had been subverted in ways you did not even see [in the U.S.] under Trump. Here we’ve had no pushback at all, whether from the media or the institutions which are supposed to act as a check. That has changed drastically over the last two months.

What is clear is that Modi started off with a far greater mass support in India than Trump ever had in America. The opposition to Trump always amounted to 50 percent of the country. That was not true here. Whether enough changes on the ground to change that for Modi is something we will learn over the next six months. For the first time, the ground has shifted.

What is becoming visible is that the promises of governance and growth that Modi had come in with have actually proved hollow. Even his core supporters, who come from a religious base, who have rallied around him whatever has happened in the past, despite the disastrous economic consequences of demonetizing the economy, people stood by him. He won election after election. That, for the first time, looks like it might change. But I’m not going to stick my neck out and say that this is going to have a permanent impact yet.

On protecting Caravan journalists

Jose: In the last year, fortunately, we haven’t lost anybody from the team. They’ve been protected now, even though a large number of journalists have lost their lives in the country, including some of our friends. Last year was a challenging year for reporters who are hitting the ground.

Now, of course, we warn our journalists when they go out in terms of the precautions they need to take or try to send them in groups. Often, with some of the stories, we don’t know what to do beyond a point. Having read some of the European history on fascism or how life was under Hitler or Mussolini, in many senses it describes how things are in India now. This is like the late 1930s in Germany, where every democratic institution which should be standing up is shot [down] one after another, and journalists are intimidated, minorities are targeted. There is a narrative of supremacy which takes center stage. An enemy has been consistently identified and targeted. Concentration camps, what we call something else in India, comes up for Muslims.

Sikhs, because they also are at the forefront of the farmers’ protest in some sense, in leadership, are being targeted — vilified like 30 years ago, 40 years ago, when there was a targeted killing of the Sikhs. Christians are randomly being picked up — nuns harassed, two, three weeks ago on a train journey. Priests and missionaries being attacked. Every religious minority, in some sense, gets targeted. The lower caste population, any leadership which comes from them, or the Indigenous community, again gets targeted.

Bal: One of the great things about The Caravan is that there’s a system of shared values which has been institutionalized. It’s not embodied in any one individual. This is something you guys may take for granted, but the fact is in India, it’s very rare.

Values become embodied, and individuals move out of institutions. Institutions change and die. This is not true of The Caravan. Everybody who’s working there believes in what we are trying to do. They are taking those risks as people who are participating on an equal basis. Also, the increased relevance, the government’s response to the stories that we are doing, becomes a validation of what we are trying to do in the field.

This is a sign that a large number of people feel the need for what amounts to journalistic work in a democracy — of questioning, of dissent, of examining things on the ground. People in our organization want to be part of this, and they are the ones today who are out in the field reporting on Covid, on crematoriums, on death. When the assault on our journalists happened, it happened on the young journalists who took, many of them, their own initiative and went out to report.

They are participants in the very idea that we share and want to take forward in journalism. That’s what really keeps them going, in some sense, is the relevance of what we are doing.