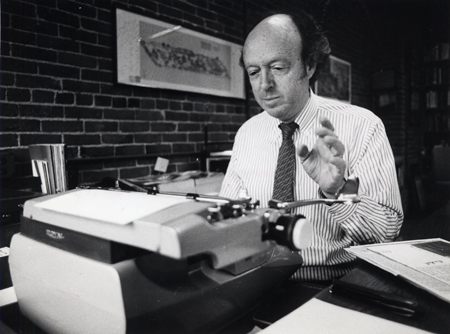

Anthony Lewis, NF ’57, died at his home in Cambridge, Massachusetts on March 25, 2013. He was 85. As a reporter for The New York Times, Lewis is credited with setting a new standard for coverage of the U.S. Supreme Court, an accomplishment that was recognized in 1963 with a Pulitzer Prize. Eight years earlier, at the age of 28, he had won his first Pulitzer for a series of articles about the unjust firing of a Navy employee during the Red Scare. For more than 30 years, Lewis wrote a column about foreign affairs for the Times’s Op-Ed page. He also wrote several books, including two about landmark Supreme Court decisions. “Gideon’s Trumpet,” about the Supreme Court decision that established a right to legal counsel for poor defendants charged with serious crimes, hasn’t been out of print since it was published in 1964.

Anthony Lewis. Photo by David L. Ryan/The Boston Globe via Getty Images

I first met Tony Lewis during the fall semester of my Nieman year, 1962. It was an idealistic as well as a hedonistic time in the United States. Jack Kennedy was in the White House, Camelot was glowing in the news, the civil rights movement was under way in the South, Martin Luther King, Jr. was dreaming his dream, Peace Corps kids were fanning out across the Third World, and the Vietnam War was still but a distant rumble.

However back in my home country, South Africa, it was a dark and ominous time. Hendrik Verwoerd, the chief architect of apartheid, was prime minister, the Sharpeville massacre, in which 69 black protesters were machine-gunned to death and 180 wounded, had just taken place resulting in Verwoerd declaring a state of emergency and outlawing the African National Congress and all other black nationalist movements. Nelson Mandela had gone underground to establish a military wing and begin an armed struggle. Things started to go bang in the night and mass arrests were being made.

Tony called on me at Harvard to discuss this bleak situation. I was just 30, fresh in the job of political correspondent for the Rand Daily Mail, South Africa’s most vigorous liberal newspaper, and I had been covering this escalating racial conflict. Tony wanted me tell him everything I could about the situation there. I was immediately struck by the depth of Tony’s knowledge of South Africa. This was my first visit to the U.S. and I was already accustomed to encountering some Americans who thought Africa was a country and South Africa the Dixie end of it. But Tony’s knowledge of the country and the dramatis personae of its unfolding drama was incredibly detailed.

This was because Tony was a liberal to the very marrow, and the looming racial clash in South Africa gripped him. He was both appalled and fascinated by it, both because it challenged the essence of his belief system and, I think, because apartheid was not just a matter of racial prejudice but was rooted in law—his subject.

As a journalist he felt a need to become part of the campaign to expose the human destructiveness of apartheid; I think he saw it was part of his contribution to the civil rights struggle in his own country, indeed to humanity in general. It also meant he identified closely with journalists like myself who were doing that within South Africa in the face of difficult and often dangerous circumstances. We became lifelong friends from that first day, and his support for all of us doing that work was immensely strengthening.

Then, of course, there was Margaret Marshall. I became friends with Margie when she was a student leader at the University of the Witwatersrand in Johannesburg. We travelled together with Senator Robert Kennedy when he was invited by the South African students union to tour South Africa in 1966. It was a stunningly successful tour during which Kennedy made a lasting impact on a whole generation of young South Africans—Margie included.

After graduating from Wits, Margie went to Harvard Law School, then into a law practice, then became a judge and finally chief justice of the Massachusetts Supreme Judicial Court. Tony, of course, was part of Robert Kennedy’s social circle around that time. Whether the senator played a role in introducing them I don’t know, but whoever played that role completed Tony’s link with what should rightly be called his other country. Their marriage was certainly the perfect link of shared interests and passions, of the law and of the lands they both loved.

As they say in one of the 11 languages of South Africa, Hamba kahle, Tony. Go well, my dear friend. We shall remember you.

Allister Sparks, NF ’63, received the 1985 Louis M. Lyons Award for Conscience and Integrity in Reporting for his reporting on apartheid and other conditions in South Africa.

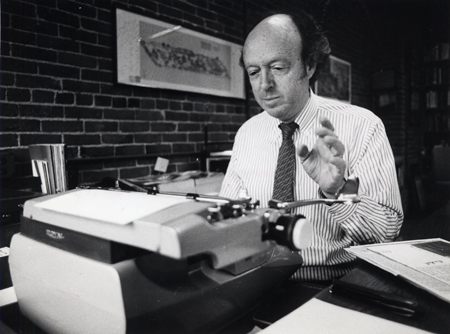

Anthony Lewis. Photo by David L. Ryan/The Boston Globe via Getty Images

I first met Tony Lewis during the fall semester of my Nieman year, 1962. It was an idealistic as well as a hedonistic time in the United States. Jack Kennedy was in the White House, Camelot was glowing in the news, the civil rights movement was under way in the South, Martin Luther King, Jr. was dreaming his dream, Peace Corps kids were fanning out across the Third World, and the Vietnam War was still but a distant rumble.

However back in my home country, South Africa, it was a dark and ominous time. Hendrik Verwoerd, the chief architect of apartheid, was prime minister, the Sharpeville massacre, in which 69 black protesters were machine-gunned to death and 180 wounded, had just taken place resulting in Verwoerd declaring a state of emergency and outlawing the African National Congress and all other black nationalist movements. Nelson Mandela had gone underground to establish a military wing and begin an armed struggle. Things started to go bang in the night and mass arrests were being made.

Tony called on me at Harvard to discuss this bleak situation. I was just 30, fresh in the job of political correspondent for the Rand Daily Mail, South Africa’s most vigorous liberal newspaper, and I had been covering this escalating racial conflict. Tony wanted me tell him everything I could about the situation there. I was immediately struck by the depth of Tony’s knowledge of South Africa. This was my first visit to the U.S. and I was already accustomed to encountering some Americans who thought Africa was a country and South Africa the Dixie end of it. But Tony’s knowledge of the country and the dramatis personae of its unfolding drama was incredibly detailed.

This was because Tony was a liberal to the very marrow, and the looming racial clash in South Africa gripped him. He was both appalled and fascinated by it, both because it challenged the essence of his belief system and, I think, because apartheid was not just a matter of racial prejudice but was rooted in law—his subject.

As a journalist he felt a need to become part of the campaign to expose the human destructiveness of apartheid; I think he saw it was part of his contribution to the civil rights struggle in his own country, indeed to humanity in general. It also meant he identified closely with journalists like myself who were doing that within South Africa in the face of difficult and often dangerous circumstances. We became lifelong friends from that first day, and his support for all of us doing that work was immensely strengthening.

Then, of course, there was Margaret Marshall. I became friends with Margie when she was a student leader at the University of the Witwatersrand in Johannesburg. We travelled together with Senator Robert Kennedy when he was invited by the South African students union to tour South Africa in 1966. It was a stunningly successful tour during which Kennedy made a lasting impact on a whole generation of young South Africans—Margie included.

After graduating from Wits, Margie went to Harvard Law School, then into a law practice, then became a judge and finally chief justice of the Massachusetts Supreme Judicial Court. Tony, of course, was part of Robert Kennedy’s social circle around that time. Whether the senator played a role in introducing them I don’t know, but whoever played that role completed Tony’s link with what should rightly be called his other country. Their marriage was certainly the perfect link of shared interests and passions, of the law and of the lands they both loved.

As they say in one of the 11 languages of South Africa, Hamba kahle, Tony. Go well, my dear friend. We shall remember you.

Allister Sparks, NF ’63, received the 1985 Louis M. Lyons Award for Conscience and Integrity in Reporting for his reporting on apartheid and other conditions in South Africa.