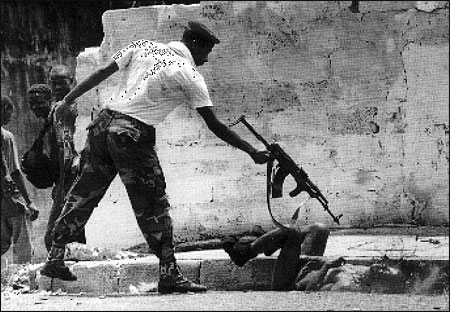

A militiaman from Charles Taylor’s National Patriotic Front shoots an unarmed prisoner. Liberia, 1997. Photo by Corinne Dufka/Reuters.

In April Newsweek magazine published a report on Serbian leader Slobodan Milosevic that described his bad-boy frown as “the face of evil.” The American press is now routinely accused of “demonizing” unappealing foreign fanatics, but defining someone as being “evil” is a more serious matter. Applied, often casually, to a violent defier of the United States’s wishes, the excursion into language of denunciation suggests unpardonable behavior that requires the strongest punishment.

The word “evil” stretches the fabric of the journalistic vocabulary, which usually tends to be political, not moral in its characterizations of leaders and their actions. Before journalists resort to using this word, as they have done frequently to describe Milosevic as the Kosovo crisis deepened, they often need prodding from propagandists and politicians. Their use of it does not occur in a vacuum. Nor are journalists much good at defining the word, even as they are using it. But they recognize the circumstantial evidence.

Before the American press describes a foreign leader as an “evil” figure, he must reveal the recognizable characteristics. This leader must be portrayable as a mad personality beyond repair, reform or redemption, a person who deserves the worst punishment the Pentagon or the CIA can devise. Journalism provides the omens and sets the stage for promise of such retribution. “One day,” Newsweek concluded, “evil will get its just reward.”

Such a leader must also exhibit a combination of pathological symptoms perhaps complicated by bad habits. Milosevic has been portrayed as an unstable character, clinging to power at any cost, and a bit of a drunk. To earn such a designation, a leader must do things that can be explained only as products of an evil nature. He must deliberately create enough suffering to take his place with the procession of cruel tyrants who have brought chaos to the 20th Century. Two men, Stalin and Hitler, whose names are synonymous with evil, lead this procession. And whatever its ruling ideology, national traditions, politics, laws or customs, the nation he dominates must be strictly under his sinister thumb, as the Soviet Union was when The New York Times’s Walter Duranty described its communist government as “applied Stalinism.”

An evil leader must be so thoroughly nasty that he makes his adversaries look good by comparison. No matter how dismal their reputations were before the conflict, now they can claim the moral high ground as “Western leaders” reluctant to apply force until goaded to action by the evil figure. Newsweek described Clinton as the leader of a “case of unmilitary characters” who surprised subordinates with the calm judgment and fortitude with which he was said to calm “his agitated crisis team.”

Whatever an evil leader has to say will be considered propaganda. If it is transparently false, it will be scoffed away; if believable it will be considered skillful propaganda. But never will anything he says be considered credible.

What emerges here is a composite portrait of Milosevic, Saddam Hussein, Iranian mullahs, Somali warlords, Afghan plotters, Japanese subway bombers or Sudanese terrorists, a list of villains stretching back at least as far as Iranian Premier Mossadegh, about whom, TIME magazine observed in a 1952 cover story, when he was its Man of the Year: “In his plaintive, singsong voice he gabbled a defiant challenge that sprang out of a hatred and envy almost incomprehensible to the West.” The truly evil act that Mossadegh committed was to nationalize Western oil interests, an understandable action evilly motivated.

The use of moralizing language makes the press susceptible to propagandists, who of course don’t mind seeing the enemy leader portrayed in a way that makes him eminently killable. This complicity by journalists, which I believe is unintentional but probably inevitable in the poisoned political atmosphere of the post-Cold War period, is perilous in a war, in which, as National Public Radio foreign correspondent Sylvia Poggioli observed in these pages in 1993, “there are no innocents.” In that article, Poggioli went on to observe that “while there is widespread agreement that the Belgrade government and Serbian fighters have been the major culprits in the conflicts, the Serbs’ entrenched attitude toward the outside world may have contributed to their being demonized and perceived by world public opinion as the sole culprits in the violent disintegration of Yugoslavia.”

The journalistic sketch of the evil figure often describes a turbulent personality in the grip of primitive and conflicting urges. The portrait is likely to consist of conjecture and analogy, often colored by the political views of the sources. In a Washington Post report before the United States’s hasty withdrawal from Somalia, about which we hear little these days, Farrah Aidid, the Somali “warlord,” was compared with Mohamed Abdullah Hassan, the “mad mullah,” who fought a guerrilla war against the British in Somalia early in the century. One of those always-convenient U.S. government sources was quoted as saying of Aidid, “This guy is crazy.” No elaboration or evidence was offered.

When reporters or editors try to explain the journalistic view of the word “evil,” they describe behavior that is incomprehensibly bad. TIME magazine essayist Lance Morrow put it this way: “Evil is the Bad hardened into the absolute. Good and evil contend in every mind. Evil comes into its own when it crosses a line and commits itself and hardens its heart, when it becomes merciless, relentless…. Evil is the word we use when we come to the limit of humane comprehension.”

This explanation is not very helpful. If journalists made up their own minds about matters like these, Morrow’s definition might be serviceable. But the government, which produces the propaganda that influences journalistic judgment, may reach its limit of “humane comprehension” when it decides that violence will be more effective than negotiation. Should reporters and editors automatically follow the lead?

In defense of moral labeling, it might be noted that early in the Nazi leader’s career, reporters as astute as Dorothy Thompson and Janet Flanner found Hitler laughably miscast as a world-threatening dictator. The evils of Nazism only became clearer when foreign correspondents such as The Chicago Tribune’s Sigrid Schultz witnessed Brown Shirt terrorists attacking Jews in Berlin, but The Tribune never allowed Schultz to depart from the moderate language and editorial distance of political observation. As the Second World War began, another Chicago reporter, Edmond Taylor, put it all together and labeled what was happening as a “strategy of terror” consisting of incessant propaganda backed by violence. Edward R. Murrow and his CBS News team knew the truth about the evil roots of the Holocaust, but New York headquarters forced them to report with such restraint in terms of emotional content or moral condemnation that the truth never quite came through in the late 1930’s.

As despicable as some of the brutality attributed to Milosevic appears to be, he is not equivalent to Hitler, even though propagandists would like him to be seen as such. The resemblance to Mussolini seems closer. Mussolini was an apprentice dictator who could never have spread his doctrines or influence much beyond Italy, except through force, as he did in Ethiopia and Libya. A good reporter named Bill Bolitho saw through the fascist revival-of-the-imperial-glory-of-Rome facadé and called Mussolini an ordinary thug.

Perhaps the pendulum has swung too far, too fast, from a time when reporters were forbidden to define in moral terms the horrors of what they saw to a time when too much is too readily and too sloppily defined by the language of morality. If journalists today sense the need to render such judgment, then perhaps we, as readers of this news, ought to expect that reporters always show us that this characterization of “evil” surfaces not from the desired beliefs of his adversaries but from evidence of the leader’s actions.

Unhallowed ground: A corpse outside the parish church of Nyarabuye offers a grim foretelling of the thousand more slaughtered inside by Hutu militia. Photo by James Nachtwey/Magnum Photos.

Michael J. Kirkhorn, a 1971 Nieman Fellow, is Director of the Journalism Program at Gonzaga University in Spokane, Washington. He’s working on a book on the independence of the press, which includes a chapter on moral judgment by journalists.