Since it emerged, the online world has been a source of trepidation for journalists. The American Journalism Review captured the foreboding in its 1999 article, "Navigating a Minefield."

There have been disruptions, mostly to the finances of news organizations, but some fears have proved false and some hopes gone unfulfilled. An acceleration of news has not led to an explosion of error. New competitors have not displaced professional journalists, although new players have emerged. Journalists have adapted and even absorbed the newcomers. The top Internet destinations for politics remain names like MSNBC, CNN and The New York Times. On the other hand, the earlier vision in the nonprofit world that the Web would become a new arena of civic discourse now seems naive. In its short history, the new medium has been predictable in only one regard — every election cycle has brought a surprise.

In 2002, I led a study, which was funded by the Pew Charitable Trusts, to assess the impact of the Internet on political journalism. We interviewed almost 300 political journalists and probed the history of the technological impact to produce "The Virtual Trail: Political Journalism on the Internet."

We pegged the beginning of the story to September 1987 when The Hotline was launched on a CompuServe bulletin board and fast became the first "must read" online digest for political reporters. A steady, ever-widening stream of insider political news has become a hallmark of the new medium, with countless Hotline imitators. The phenomenon moved to the mainstream in 2002 with the launching of ABC News's The Note, an internal memorandum repurposed into a sassy online offering. The progression hit another milestone in 2007 when the Allbritton Corporation launched Politico, the first Internet-centric news organization to rival the old media by enlisting top political journalists.

The result of all of this has been a quantum increase in the volume of political news, although targeted to an elite audience.

Web sites emerged in a significant way in the 1996 election, but it was in 2000 that the new medium exploded with experimentation, largely with a flood of print content. New players in political coverage got into the act, including entrepreneurs with political dot-coms and nonprofit organizations seeking to turn the net into a civic tool. The best example of the latter was Web, White and Blue 2000, a project funded by the Markle Foundation that enlisted 17 cosponsoring sites of major news organizations and Internet portals. The mothballed site, which brimmed with textual content, remains an interesting window on the early civic Web. The largest of the political dot-coms was Voter.com, a hybrid of journalism and political activism.

The chief criticism of the 2000 environment was not that it was frivolous or polarizing — today's criticism — but that it produced information overload. Neither Web, White and Blue nor Voter.com lived to see another election cycle, as the hangover from the exuberance converged with the dot-com crash on Wall Street. It was in that lull that we conducted our study, which concluded that political journalists were adapting to the technological changes and making good use of new reporting tools, particularly in tracking campaign finances. The study found passivity in covering aspects of the online campaign beyond its novelty, a continuing problem. We spotted the rise of insider news. We were less than prescient in declaring "the experimentation and excitement have waned." We did not see the blogosphere or YouTube coming.

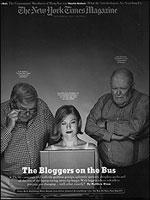

The political bloggers became the rage of the 2004 cycle and their impact is a familiar story. Dan Rather saw his career up-ended by conservative bloggers who raised doubts about CBS News's report on President Bush's National Guard service. Bush himself took notice of the blogs in a presidential debate when he denied he would reinstate the draft. "I hear there's rumors on the Internets," he said. The blogs achieved a bit of political journalism glory on September 24, 2004 when The New York Times Magazine ran a cover with Wonkette, flanked by those Boys on the Bus R.W. Apple, and Jack Germond, both looking over her shoulder in puzzlement.

However, rather than become a new journalistic prototype, most bloggers have stuck with political activism. All the presidential campaigns in 2008 have worked hard to enlist bloggers as a new media royalty. Some bloggers have turned more journalistic, developing their own small news staffs. Arianna Huffington turned her blog, The Huffington Post, into a self-proclaimed "Internet Newspaper;" Joshua Micah Marshall, who operates several interconnected sites, won a 2007 George Polk award for excellence in journalism. Traditional reporters also have turned to blogging, mostly by reporting campaign tidbits without much opinionated fervor.

And there is no better example of the co-option of the new political voices than in one Ana Marie Cox, a.k.a. Wonkette. The face of the bloggers in 2004 went to work for Time magazine.

There have been disruptions, mostly to the finances of news organizations, but some fears have proved false and some hopes gone unfulfilled. An acceleration of news has not led to an explosion of error. New competitors have not displaced professional journalists, although new players have emerged. Journalists have adapted and even absorbed the newcomers. The top Internet destinations for politics remain names like MSNBC, CNN and The New York Times. On the other hand, the earlier vision in the nonprofit world that the Web would become a new arena of civic discourse now seems naive. In its short history, the new medium has been predictable in only one regard — every election cycle has brought a surprise.

In 2002, I led a study, which was funded by the Pew Charitable Trusts, to assess the impact of the Internet on political journalism. We interviewed almost 300 political journalists and probed the history of the technological impact to produce "The Virtual Trail: Political Journalism on the Internet."

We pegged the beginning of the story to September 1987 when The Hotline was launched on a CompuServe bulletin board and fast became the first "must read" online digest for political reporters. A steady, ever-widening stream of insider political news has become a hallmark of the new medium, with countless Hotline imitators. The phenomenon moved to the mainstream in 2002 with the launching of ABC News's The Note, an internal memorandum repurposed into a sassy online offering. The progression hit another milestone in 2007 when the Allbritton Corporation launched Politico, the first Internet-centric news organization to rival the old media by enlisting top political journalists.

The result of all of this has been a quantum increase in the volume of political news, although targeted to an elite audience.

Web sites emerged in a significant way in the 1996 election, but it was in 2000 that the new medium exploded with experimentation, largely with a flood of print content. New players in political coverage got into the act, including entrepreneurs with political dot-coms and nonprofit organizations seeking to turn the net into a civic tool. The best example of the latter was Web, White and Blue 2000, a project funded by the Markle Foundation that enlisted 17 cosponsoring sites of major news organizations and Internet portals. The mothballed site, which brimmed with textual content, remains an interesting window on the early civic Web. The largest of the political dot-coms was Voter.com, a hybrid of journalism and political activism.

The chief criticism of the 2000 environment was not that it was frivolous or polarizing — today's criticism — but that it produced information overload. Neither Web, White and Blue nor Voter.com lived to see another election cycle, as the hangover from the exuberance converged with the dot-com crash on Wall Street. It was in that lull that we conducted our study, which concluded that political journalists were adapting to the technological changes and making good use of new reporting tools, particularly in tracking campaign finances. The study found passivity in covering aspects of the online campaign beyond its novelty, a continuing problem. We spotted the rise of insider news. We were less than prescient in declaring "the experimentation and excitement have waned." We did not see the blogosphere or YouTube coming.

The political bloggers became the rage of the 2004 cycle and their impact is a familiar story. Dan Rather saw his career up-ended by conservative bloggers who raised doubts about CBS News's report on President Bush's National Guard service. Bush himself took notice of the blogs in a presidential debate when he denied he would reinstate the draft. "I hear there's rumors on the Internets," he said. The blogs achieved a bit of political journalism glory on September 24, 2004 when The New York Times Magazine ran a cover with Wonkette, flanked by those Boys on the Bus R.W. Apple, and Jack Germond, both looking over her shoulder in puzzlement.

However, rather than become a new journalistic prototype, most bloggers have stuck with political activism. All the presidential campaigns in 2008 have worked hard to enlist bloggers as a new media royalty. Some bloggers have turned more journalistic, developing their own small news staffs. Arianna Huffington turned her blog, The Huffington Post, into a self-proclaimed "Internet Newspaper;" Joshua Micah Marshall, who operates several interconnected sites, won a 2007 George Polk award for excellence in journalism. Traditional reporters also have turned to blogging, mostly by reporting campaign tidbits without much opinionated fervor.

And there is no better example of the co-option of the new political voices than in one Ana Marie Cox, a.k.a. Wonkette. The face of the bloggers in 2004 went to work for Time magazine.