During the decades of covering the Communist states of Europe, foreign correspondents were challenged to draw conclusions, make educated guesses, and deliver informed conjectures on the basis of modest hard evidence.

If correspondents in Washington deliver a story on 75 percent solid information and 25 percent on lesser evidence, that's normal. But writing from Moscow, Bucharest, Prague or Sofia in the bad old days a reporter was fortunate if he, or she, could show 50 percent hard information. Budapest and Warsaw were easier because of the different nature of the ruling parties there; and East Germany was unique because West Germans had sources that penetrated the wall.

This is why the newly published book, "The KGB File of Andrei Sakharov," is so important. Here is hard information from the inner machinations of the Communist Party of the old Soviet Union that answers questions for those of us who stared at the Kremlin and party headquarters and wondered, "What is really going on in there?" Published by the Yale University Press as part of the invaluable series "Annals of Communism," this book shows how the activities of the mild-mannered, brilliant physicist Andrei Sakharov preoccupied the ruling Communist Party politburo for more than two decades until his death in 1989.

The tension between the scientist and official hero and the ruling clique played out offstage until late 1972, when Sakharov was interviewed for the first time by a Western journalist, Jay Axelbank of Newsweek. From then until his death, Sakharov intensified his campaign to advance the cause of human rights for all citizens of the Soviet Union, generating international support and a substantial internal following until the old system collapsed and Mikhail Gorbachev took the party leadership. Sakharov was elected to the first parliament of the post-Communist era and became the most important political figure in the country; he was drafting a new constitution for Russia when his exhausted heart collapsed at age 68.

His story percolated so many years that only the Kremlin junkies fully appreciate his accomplishment. He has been compared to many historic figures, but my favorite association is with Nelson Mandela, the founder of the modern South Africa. Like Mandela, Sakharov was able to sublimate the bitterness he must have felt toward the cruel and stupid leaders who made his life miserable, destroying his health but never quashing his spirit.

Sakharov's Situation

This book is not a spy story. There are no revelations on how the KGB listened to everyone's telephone conversations, followed, photographed and harassed foreigners and domestic troublemakers, potential and real. Such operational records of the secret police were presumably destroyed, leaving this record of dry, haunted, bureaucratic memoranda from the KGB chiefs to the Central Committee, Communist Party of the Soviet Union (CPSU), and its politburo.

One assumption most accepted by correspondents was that the KGB could do pretty much what it wanted with the targets of its interest, especially after 20 years of watching and waiting. So why didn't they squash the wistful-looking physicist and his strong-willed second wife, Yelena Bonner, a pediatrician? They were perfect candidates for the definition of insanity used by KGB boss Yuri Andropov of individuals acting outside the norms of Soviet citizenship.

The answer is clear: The political leaders of that era, led by Leonid Brezhnev, were determined to carry forward their policy of detente, relaxed tension, with the Western powers. They knew from the day Sakharov issued his first public appeal in 1968 in The New York Times that he was a special case. Moscow in the 1970's was so anxious to gain economic assistance and cooperation from the West that the top leaders had to hold the goons on their leashes.

Detente relaxed some controls over the foreign press, especially the Americans, so that our reporting about Sakharov's work provided a shield for him. The police smothered him with surveillance and harassed him and his wife, but they had to keep him alive. And they had to keep him sealed up inside the country, because if he were allowed to travel or emigrate, he would have attracted an international following antithetical to the Kremlin.

His case was different from Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn, the remarkable novelist who was forced into exile in 1974 when the KGB thought it had stamped out the nascent democratic underground. The police considered the two men to be collaborators, but they were different personalities; the writer was self-centered and a Slavic nationalist and religious mystic. He disappeared into Vermont and later returned home and faded from public view. Sakharov was a humanist concerned with all of Communism's victims.

Reporting on Dissidents

Correspondents could only guess how deeply these courageous men and their small circle of allies annoyed the Kremlin. We differed on how much attention to pay to the disparate dissident groups that had appeared for the first time in modern Soviet history, although there was a consensus that it was wrong to devote too much time to reporting their activities. In resignation that there were limits to our reporting on the dissidents, one colleague observed, "It is their country." The dissidents hardly constituted a political "opposition." The groups were not well organized, and there were few individuals involved. They were isolated across the vast land. Still, the fact was that brave men and women, young and old, struggling at great risk against the suffocating controls of the monolithic Soviet system, was news.

Some reporters held back, citing one notorious example of a dozen radical Jewish youth who drew wide attention by staging a brief demonstration in Red Square. It turned out that two or three of them were KGB informers, like the many American Communists who worked for the FBI. Henry Shapiro, near retirement after 40 years in Moscow, refused to allow his United Press International (UPI) correspondents to compete with reporters from The Associated Press (AP) and Reuters in covering the dissidents. Stories on this topic were filed only on orders from UPI's New York office until Shapiro retired in 1973. On the other extreme, David Bonavia, a brilliant correspondent for The Times of London when it was one of the world's most influential newspapers, virtually adopted Pyotr Yakir, a fat, alcoholic dissident who generated genuine sympathy since he spent his youth in a prison camp after his father, a famous general, was executed by Stalin. Yakir spent long days in Bonavia's apartment, eating his food and drinking his vodka, until he was arrested with an ally, Viktor Krasin, in 1972. Bonavia was expelled in early 1972.

Eighteen months later, Yakir and Krasin appeared at a KGB press conference to denounce their previous activities, suggesting correspondents should be wary of so-called "dissidents." Yakir urged Sakharov to halt his political work that only generated "propaganda against our homeland." The hand-typed, carbon-copied "A Chronicle of Current Events" that kept correspondents informed of underground activities was shut down, and several other dissidents were arrested in 1974, and the KGB sensed victory.

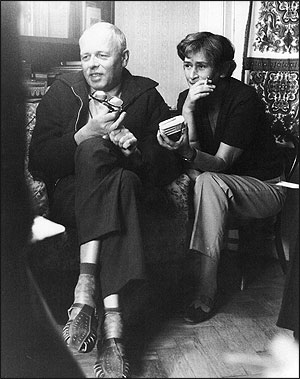

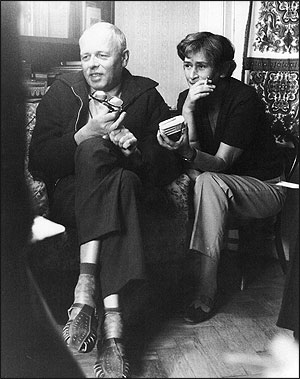

Andrei Sakharov and Yelena Bonner, Moscow 1973. Photo by Murray Seeger.

Sakharov's Influence

As the KGB swept through the dissidents, Sakharov emerged from the shadows and turned to the foreign press for help. His 1972 interview with Newsweek was followed the next year with a television conversation with Olle Stenholm of Sweden. Soon after, Sakharov reached into the Jewish community to borrow a trilingual interpreter, Kirill Khenkin, so he could meet with a wider selection of correspondents.

As Sakharov generated more support from foreign politicians, scientists and writers and European Communists, the KGB memos took on a more ominous tone. Sakharov was a true hero: a designer of the Soviet hydrogen bomb who turned peacenik; a member of the privileged intelligentsia who sought rights for all victims of Soviet power; a rich man who gave away his fortune and lived on 800 rubles a month from the Academy of Sciences and his wife's pension.

In 1975, Sakharov's international status was elevated when was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize. The KGB considered this proof of a massive international conspiracy against the Soviet Union, noting the award was made when Yelena Bonner was traveling in the West for medical treatment and could receive the prize and read Sakharov's acceptance speech. In November 1975, the Soviet police hit the panic button:

"The Committee of State Security [KGB] of the USSR Council of Ministers and the USSR Procurator's Office have reported to the Central Committee of the CPSU about Sakharov's anti-Soviet activities. ... Recently, having embarked on the path of an open struggle against Soviet power, he is divulging state secrets to the enemy that pertain to the most vital defense issues of the country. ..."

The goons proposed a series of criminal charges to be brought against Sakharov in addition to having him expelled from the Academy of Sciences. He and Bonner should be banished to Sverdlovsk. They reacted again after Sakharov talked with Hedrick Smith of The New York Times and then suggested to George Krimsky, AP bureau chief, that a bomb attack in a Moscow subway might have been a KGB action. That ended the truce with American journalists; Krimsky was expelled in 1977, the first American kicked out since 1970.

Finally, in 1980, the KGB won its argument that Sakharov was a real danger to party control of the state, weakened now by poor economic performance, the rise of Solidarity in Poland, and war in Afghanistan. The politburo agreed to expel Sakharov and Bonner to Gorky, an industrial city closed to foreigners. Still, the pair was able to get messages to the outside world giving details of the dirty tricks played against them. At the same time, the CPSU was collapsing: Three supreme leaders died in rapid succession, including Yuri Andropov, the architect of the anti-Sakharov campaign.

In 1986, Gorbachev, anxious to gain credibility as a reformer, informed Sakharov and Bonner that they could return to their small apartment on Chkalov Street. The secret police still watched Sakharov as he rose to become the most popular politician in the new Russia.

It is easy to overemphasize the importance of foreign reporting in making a shy physicist into an international hero and major cause for the collapse of Soviet Communism. On other hand, if Sakharov had not used international communications to plead his cause, he most likely would have been locked up in a mental institution and forgotten like many lesser-known dissidents.

Of the several lessons from this history, one should be absorbed by those journalists who portrayed Andropov as a Western-oriented liberal and political reformer. This KGB record proves he was an evil schemer determined to carry on the Communist tradition of destroying the country's most valuable citizens, in this case, one the greatest public figures of the 20th century.

Murray Seeger, a 1962 Nieman Fellow, covered Russia and East Europe for the Los Angeles Times for 10 years. He has recently published "Discovering Russia: 200 Years of American Journalism," a study of how Americans formed their opinions about that country.

If correspondents in Washington deliver a story on 75 percent solid information and 25 percent on lesser evidence, that's normal. But writing from Moscow, Bucharest, Prague or Sofia in the bad old days a reporter was fortunate if he, or she, could show 50 percent hard information. Budapest and Warsaw were easier because of the different nature of the ruling parties there; and East Germany was unique because West Germans had sources that penetrated the wall.

This is why the newly published book, "The KGB File of Andrei Sakharov," is so important. Here is hard information from the inner machinations of the Communist Party of the old Soviet Union that answers questions for those of us who stared at the Kremlin and party headquarters and wondered, "What is really going on in there?" Published by the Yale University Press as part of the invaluable series "Annals of Communism," this book shows how the activities of the mild-mannered, brilliant physicist Andrei Sakharov preoccupied the ruling Communist Party politburo for more than two decades until his death in 1989.

The tension between the scientist and official hero and the ruling clique played out offstage until late 1972, when Sakharov was interviewed for the first time by a Western journalist, Jay Axelbank of Newsweek. From then until his death, Sakharov intensified his campaign to advance the cause of human rights for all citizens of the Soviet Union, generating international support and a substantial internal following until the old system collapsed and Mikhail Gorbachev took the party leadership. Sakharov was elected to the first parliament of the post-Communist era and became the most important political figure in the country; he was drafting a new constitution for Russia when his exhausted heart collapsed at age 68.

His story percolated so many years that only the Kremlin junkies fully appreciate his accomplishment. He has been compared to many historic figures, but my favorite association is with Nelson Mandela, the founder of the modern South Africa. Like Mandela, Sakharov was able to sublimate the bitterness he must have felt toward the cruel and stupid leaders who made his life miserable, destroying his health but never quashing his spirit.

Sakharov's Situation

This book is not a spy story. There are no revelations on how the KGB listened to everyone's telephone conversations, followed, photographed and harassed foreigners and domestic troublemakers, potential and real. Such operational records of the secret police were presumably destroyed, leaving this record of dry, haunted, bureaucratic memoranda from the KGB chiefs to the Central Committee, Communist Party of the Soviet Union (CPSU), and its politburo.

One assumption most accepted by correspondents was that the KGB could do pretty much what it wanted with the targets of its interest, especially after 20 years of watching and waiting. So why didn't they squash the wistful-looking physicist and his strong-willed second wife, Yelena Bonner, a pediatrician? They were perfect candidates for the definition of insanity used by KGB boss Yuri Andropov of individuals acting outside the norms of Soviet citizenship.

The answer is clear: The political leaders of that era, led by Leonid Brezhnev, were determined to carry forward their policy of detente, relaxed tension, with the Western powers. They knew from the day Sakharov issued his first public appeal in 1968 in The New York Times that he was a special case. Moscow in the 1970's was so anxious to gain economic assistance and cooperation from the West that the top leaders had to hold the goons on their leashes.

Detente relaxed some controls over the foreign press, especially the Americans, so that our reporting about Sakharov's work provided a shield for him. The police smothered him with surveillance and harassed him and his wife, but they had to keep him alive. And they had to keep him sealed up inside the country, because if he were allowed to travel or emigrate, he would have attracted an international following antithetical to the Kremlin.

His case was different from Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn, the remarkable novelist who was forced into exile in 1974 when the KGB thought it had stamped out the nascent democratic underground. The police considered the two men to be collaborators, but they were different personalities; the writer was self-centered and a Slavic nationalist and religious mystic. He disappeared into Vermont and later returned home and faded from public view. Sakharov was a humanist concerned with all of Communism's victims.

Reporting on Dissidents

Correspondents could only guess how deeply these courageous men and their small circle of allies annoyed the Kremlin. We differed on how much attention to pay to the disparate dissident groups that had appeared for the first time in modern Soviet history, although there was a consensus that it was wrong to devote too much time to reporting their activities. In resignation that there were limits to our reporting on the dissidents, one colleague observed, "It is their country." The dissidents hardly constituted a political "opposition." The groups were not well organized, and there were few individuals involved. They were isolated across the vast land. Still, the fact was that brave men and women, young and old, struggling at great risk against the suffocating controls of the monolithic Soviet system, was news.

Some reporters held back, citing one notorious example of a dozen radical Jewish youth who drew wide attention by staging a brief demonstration in Red Square. It turned out that two or three of them were KGB informers, like the many American Communists who worked for the FBI. Henry Shapiro, near retirement after 40 years in Moscow, refused to allow his United Press International (UPI) correspondents to compete with reporters from The Associated Press (AP) and Reuters in covering the dissidents. Stories on this topic were filed only on orders from UPI's New York office until Shapiro retired in 1973. On the other extreme, David Bonavia, a brilliant correspondent for The Times of London when it was one of the world's most influential newspapers, virtually adopted Pyotr Yakir, a fat, alcoholic dissident who generated genuine sympathy since he spent his youth in a prison camp after his father, a famous general, was executed by Stalin. Yakir spent long days in Bonavia's apartment, eating his food and drinking his vodka, until he was arrested with an ally, Viktor Krasin, in 1972. Bonavia was expelled in early 1972.

Eighteen months later, Yakir and Krasin appeared at a KGB press conference to denounce their previous activities, suggesting correspondents should be wary of so-called "dissidents." Yakir urged Sakharov to halt his political work that only generated "propaganda against our homeland." The hand-typed, carbon-copied "A Chronicle of Current Events" that kept correspondents informed of underground activities was shut down, and several other dissidents were arrested in 1974, and the KGB sensed victory.

Andrei Sakharov and Yelena Bonner, Moscow 1973. Photo by Murray Seeger.

Sakharov's Influence

As the KGB swept through the dissidents, Sakharov emerged from the shadows and turned to the foreign press for help. His 1972 interview with Newsweek was followed the next year with a television conversation with Olle Stenholm of Sweden. Soon after, Sakharov reached into the Jewish community to borrow a trilingual interpreter, Kirill Khenkin, so he could meet with a wider selection of correspondents.

As Sakharov generated more support from foreign politicians, scientists and writers and European Communists, the KGB memos took on a more ominous tone. Sakharov was a true hero: a designer of the Soviet hydrogen bomb who turned peacenik; a member of the privileged intelligentsia who sought rights for all victims of Soviet power; a rich man who gave away his fortune and lived on 800 rubles a month from the Academy of Sciences and his wife's pension.

In 1975, Sakharov's international status was elevated when was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize. The KGB considered this proof of a massive international conspiracy against the Soviet Union, noting the award was made when Yelena Bonner was traveling in the West for medical treatment and could receive the prize and read Sakharov's acceptance speech. In November 1975, the Soviet police hit the panic button:

"The Committee of State Security [KGB] of the USSR Council of Ministers and the USSR Procurator's Office have reported to the Central Committee of the CPSU about Sakharov's anti-Soviet activities. ... Recently, having embarked on the path of an open struggle against Soviet power, he is divulging state secrets to the enemy that pertain to the most vital defense issues of the country. ..."

The goons proposed a series of criminal charges to be brought against Sakharov in addition to having him expelled from the Academy of Sciences. He and Bonner should be banished to Sverdlovsk. They reacted again after Sakharov talked with Hedrick Smith of The New York Times and then suggested to George Krimsky, AP bureau chief, that a bomb attack in a Moscow subway might have been a KGB action. That ended the truce with American journalists; Krimsky was expelled in 1977, the first American kicked out since 1970.

Finally, in 1980, the KGB won its argument that Sakharov was a real danger to party control of the state, weakened now by poor economic performance, the rise of Solidarity in Poland, and war in Afghanistan. The politburo agreed to expel Sakharov and Bonner to Gorky, an industrial city closed to foreigners. Still, the pair was able to get messages to the outside world giving details of the dirty tricks played against them. At the same time, the CPSU was collapsing: Three supreme leaders died in rapid succession, including Yuri Andropov, the architect of the anti-Sakharov campaign.

In 1986, Gorbachev, anxious to gain credibility as a reformer, informed Sakharov and Bonner that they could return to their small apartment on Chkalov Street. The secret police still watched Sakharov as he rose to become the most popular politician in the new Russia.

It is easy to overemphasize the importance of foreign reporting in making a shy physicist into an international hero and major cause for the collapse of Soviet Communism. On other hand, if Sakharov had not used international communications to plead his cause, he most likely would have been locked up in a mental institution and forgotten like many lesser-known dissidents.

Of the several lessons from this history, one should be absorbed by those journalists who portrayed Andropov as a Western-oriented liberal and political reformer. This KGB record proves he was an evil schemer determined to carry on the Communist tradition of destroying the country's most valuable citizens, in this case, one the greatest public figures of the 20th century.

Murray Seeger, a 1962 Nieman Fellow, covered Russia and East Europe for the Los Angeles Times for 10 years. He has recently published "Discovering Russia: 200 Years of American Journalism," a study of how Americans formed their opinions about that country.