Our projects team at the Asbury Park Press had spent five months tracking the $300 million collapse of a local real estate tycoon in 2006. The story was interesting enough, as the 33-year-old had leveraged his prominent family connections to attract wealthy but naive investors and lull banks into lending without the usual due diligence.

But after an interview, one local banker told me about an even better story—national in scope with implications for Wall Street and the financial markets. To be certain, it was a large-scale story for a medium-sized newspaper like the Asbury Park Press to handle.

Even in our high-tech age, many editors and reporters—especially at smaller outlets with tough staffing and time constraints—will not attempt to tackle such a large story (or even a smaller one) that requires reporters doing original research, crunching numbers, and providing analysis. There are plenty of reasons to be found to avoid this kind of heavy lifting. Editors, feeling too pressed by daily deadlines, are reluctant to put reporters on such time-consuming tasks, and many reporters still balk at such undertakings, observing that they fled to journalism to avoid math. In many newsrooms, computer expertise has been left to a select few, as the rank-and-file stick to their beats.

Yet through the use of relatively basic computer-assisted reporting, the largest financial story of this decade—the subprime mortgage crisis—was told by the Asbury Park Press. Our coverage garnered national awards and, as importantly, won praise from local readers.

Crunching the Numbers

It all began with that after-interview chat with a local banker. The defunct developer was only a symptom of a widespread disease, he said. Banks across the country had dramatically lowered their underwriting standards to provide money to just about anyone with a pulse. The country’s culture and attitude toward finances had changed so much that many people were refinancing their house two, three or four times to pay for Florida vacations for their kids and Hummers for their driveways. The banker said he tried, but failed, to convince customers not to refinance their homes yet again for more lifestyle expenses. And, he said, a whole new class of loans—called “subprime”—had come to dominate the market so much that a conservative bank like his could no longer compete.

At the New Jersey shore, real estate is always a hot topic. Eighty percent of the houses in the Press’s coverage area are lived in by their owners. Most of the rest serve as summer beach houses for residents around the state. The shore holds some of the most expensive property in America. Although the housing mania had not quite reached the hysterical heights of Southern California or Florida, prices at the northern Jersey shore, where the Press circulates, had gone up nearly 150 percent in the previous 10 years.

Though the banker had described a national story, I could also see how it could be intensely localized. There was no reason to shy away. As I told my editor, “Everyone in our area who owns a house cares about this story.”

I ordered the federal database of mortgage applications, known as the Home Mortgage Disclosure Act data. That prodigious computer record gave me a profile on every mortgage application in the country: the amount, the applicant’s income, their gender and race, whether the loan would be used for a purchase or a refinance, whether it was for a primary residence or other home. There was also a variable that let me know whether the loan was subprime because it came with a higher interest rate.

Even better for a regional paper like the Asbury Park Press, the data was coded so that I could compile results for the state, our local counties, and even for neighborhood census tracts. Instant local news. I loaded the data into a program used for advanced statistics, SPSS, and parsed off smaller data sections into Microsoft Access and Excel. Then I hunkered down to find the story. Soon, with the computer running at full speed, I had a three-inch binder full of printouts.

Meanwhile, I read Federal Reserve studies on household finance, spoke to experts, and canvassed our area to speak with local mortgage bankers, appraisers, real estate brokers, foreclosure investors, and troubled mortgage loan borrowers.

I was putting the final polish on the “Home Roulette” series just as the first subprime shudders hit Wall Street. We published in March 2007. The package included online maps that readers could use to focus on various dimensions of this problem in their town. On one map, a deep brown cluster quickly identified areas in the state where more than 30 percent of the mortgages relied on subprime loans; on a different map, this same color indicated places where at least half of homeowners had refinanced within a two-year span of time.

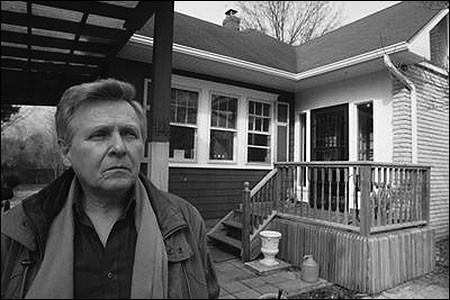

Every story in this series featured local people, and photographs that ran side-by-side with our reporting showed readers how these people’s lives had been affected—people who could have been their neighbors.

The Asbury Park Press suddenly looked very smart, and if the crisis had waited just a bit to explode, we might have been hailed as geniuses.

REFERRED ARTICLE

"Home Roulette"

—Jason MethodI did not stop covering the story even as it became daily national news. I wrote about rising foreclosures, prepayment penalties, the effect of a U.S. Supreme Court decision on state regulation, and a national mortgage fraud under investigation by the FBI (which included local victims.) In the fall, my analysis of the new federal mortgage data ran in our paper during the same week The Wall Street Journal reported on their examination of the same information.

It would be preposterous to think a paper like the Asbury Park Press could run with top business reporting organizations in covering the biggest financial story of the decade. But last April I felt honored to be named as a finalist in the Scripps Howard National Journalism Awards. (The Wall Street Journal’s 14-member subprime team won the award in the business/economics reporting category. Two reporters for Bloomberg were also finalists.) Just as important as earning recognition within our profession, knowing that readers loved the mortgage stories reminded us of the value of what we’d done. The stories were top online draws on the days they ran, and we received scores of complimentary e-mails and calls.

Early this year, a group of real estate business people and bankers invited me to dinner to talk about the series. They recalled key details of stories written months earlier, such as the $5,000 pool table purchased by one couple in debt.

CAR: An Essential Newsroom Tool

The beauty of computer-assisted reporting (CAR) is that, in this day of easily accessible data, computer expertise can be a great equalizer. It can allow smart reporters at any size news organization to saw wood on national or state issues and drill the story down, sometimes to the neighborhood level. Certainly, the benefits of those efforts can be seen, especially online, as interactive databases and maps are favorites on news sites.

But many frontline reporters have not joined in the computer-assisted reporting revolution, some 15 years after its advent. Instead, they wait to ask the computer experts in their newsroom for help, if they ask at all. In recent years, CAR has, for many, evolved into a priesthood of computer specialists who have long since abandoned writing words in favor of writing code, queries and command statements as they master more and more advanced programs. As a consequence, reporters can shy away from learning how to integrate CAR into their work, and editors caught in the crush of meetings and deadlines—especially those at smaller news organizations—can overlook the potentially powerful contributions that the CAR basics could make even in daily reporting.

Spreadsheets, databases and online services such as LexisNexis offer immediate help for even the most pressing deadline stories. Classic programs for CAR practitioners, like SPSS and the ArcView mapping program, offer sophisticated analysis for a relatively modest price. There is an investment of time required to learn, but it can pay immediate dividends.

Whether the story is about real estate, foster care for children, school performance, taxes, government bureaucracy, or even Mother’s Day, there are numbers and records that can be analyzed with tools that have been around for more than a decade. CAR gives journalists the opportunity to dig for truth in data, and the comparative analysis that a computer can do often reveals pertinent questions. What reporters are able to learn from using CAR provides readers with knowledge and insights that can cut through the clutter of opinionated noise and celebrity obsession.

It also can allow even relatively small news operations to delve into problems affecting the global community, yet speak to readers and viewers right around the block.

Jason Method was an investigative/computer-assisted projects reporter at the Asbury Park Press for nine years before his promotion to bureau chief in July. He was on the Press’s team for the “Profiting from Public Service” series, which won the Selden Ring Award, a National Headliner Award, and was a finalist for The Shorenstein Center’s Goldsmith Prize in 2004 at Harvard University.