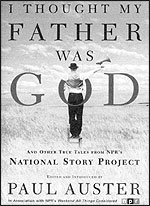

I Thought My Father Was God: And Other True Tales From NPR’s National Story Project

Edited by Paul Auster

Henry Holt. 383 Pages. $25.Once, when I was working on a weekly news show, the host was interviewing a foreign correspondent in the Balkans. It wasn’t going well. The correspondent could describe with precision the ethnic factions, the regional leaders, and the political costs at stake—all perfectly distilled and perfectly remote. The foreign news remained foreign, with nothing to connect the politics to real people and their lives. Since the interview was being taped before air, the host, lost in mind-numbing acronyms, stopped midway through and searched for a way into the topic. He asked for description, a sense of place, a conversation in a cafe, anything. Finally, at a loss, he pleaded, “Couldn’t you just tell us a story?”

It’s the question that gets asked a lot, but maybe not enough, the hunt for the thing that is remembered long after the political analysis has faded away. But imagine being able to have someone tell a story that needs no news peg to run, no nut graf to explain why; a tale that exists only to be told. The possibilities are endless—or at least they can stretch into the thousands. Just ask Paul Auster and the people at National Public Radio’s (NPR) “Weekend All Things Considered.”

In October 1999, Auster, a writer, appeared on “Weekend All Things Considered” and asked listeners to tell a story. The criteria were simple. As Auster later put it, “The stories had to be true, and they had to be short, but there would be no restrictions as to subject matter or style.” The results—179 culled from thousands entered— have been put together in “I Thought My Father Was God: And Other True Tales From NPR’s National Story Project.” But the real results have been heard on NPR for the past two years, with Auster reading each submission the first Saturday of every month.

RELATED ARTICLES

"Bicoastal"

- Beth Kivel

"Salt Lake City, Utah, 1975"

- Steve HaleIt was a remarkable project. As Jackie Lyden, a host of “Weekend All Things Considered,” said, reporters as conduits for people’s stories usually “carve them up a wee bit,” but that this was “a chance to hear a listener story incarnate.” Auster described the project as “the importance of listening and honoring what people have to say” and, maybe more candidly, an attempt to see if we are all alike in our oddities.

“I Thought My Father was God” is broken down into categories: Animals, Objects, Families, Slapstick, Strangers, War, Love, Death, Dreams and Meditations (if that last category sounds the most amorphous, that’s because it is, and it’s the weakest section in the book). Most are stories in the true sense, the kind that when they’re read on air keep you in the car listening, despite the fact that you’ve reached your destination—that golden moment all radio producers dream of. Some read like family lore, passed down from generation to generation. Others come across as secrets revealed.

Nearly all the stories are memorable, from the mundane to the miraculous. In one story, “Danny Kowalski,” Charlie Peters of Santa Monica, California, tells of his ailing father, whose one perk from a sales job in the 1950’s was the use of a Jaguar luxury car. For this, Peters feels shame when dropped off at his working-class school, especially when he’s glared at by one of the kids, a tough named Danny Kowalski. The story ends when Peter’s father dies, the company takes back the car, and he heads to school with his grandmother.

“When we approached the school yard that morning,” Peters says, “I could see Danny hanging on the fence, same place as always, his jacket collar turned up, his hair perfectly coifed, his boots recently sharpened. But this time, as I passed him in the company of this feeble, elderly woman and with no elitist English car in sight, I felt as if a wall had been taken down between us. Now I was more like Danny, more like his friends. We were finally equals. Relieved, I walked into the school yard. And that was the morning Danny Kowalski beat me up.”

In another story, a cardiac surgeon, who identifies himself only as Dr. G, writes of a patient who required a risky coronary bypass. The patient, in his mid-70’s, suffers brain damage but, incredibly, the damage proves to be restorative. The elderly patient awakens believing he is 20 years younger, with the strength and energy to match. “Prior to his heart surgery,” the doctor says, “my patient had been an alcoholic, a wife-abuser, and impotent for 20 years. After his cardiac arrest and resuscitation—and the loss of 20 years of memory—he had forgotten all these things about himself. He stopped drinking. He began sleeping with his wife again and became a loving husband. This lasted for more than a year. And then, one night, he died in his sleep.”

There is much, much more in this collection, and this is where I have to urge anyone interested in “I Thought My Father Was God,” to hear these stories first. Buy the audiotapes (Harper Audio, $34.95, nine hours/six cassettes). Radio is a great storytelling medium, with the listener making up the pictures with no sense of what the next word or line will be. The listener can be engaged in one thing—chopping the carrots, driving to the store—and entirely focused on another. Auster has a great delivery, reading each story in a low-key but lively way, letting the words speak for themselves. These are stories that benefit in the hearing.

In describing the goals of the National Story Project, Auster has written that he was trying to create “an archive of facts, a museum of American reality.” He, and all those who contributed, have succeeded. These stories document America, and they take on a different dimension post-September 11—something Auster himself acknowledged late last year when he read one of the final stories in the project, “One Autumn Afternoon.” In that tale, the depiction of a bucolic rural home in upstate New York in 1944 turns dark with the presence of a letter announcing the death of an older brother in battle. But all these stories, ugly and beautiful, funny and strange, add up to create a portrait of who we are as Americans.

Who knows what the next step will be for the National Story Project? It is now in hibernation, possibly to return in some form later. With so many American voices now documented, maybe it’s time to put out an international appeal and find out what stories the rest of the world has to tell.

Andrew Sussman, a 2001 Nieman Fellow, produces Public Radio International’s “The World.”