As the profitability of traditional Chinese media plummets, journalists are increasingly beginning to transform themselves, with the acceptance of bribes for writing positive stories becoming more and more common among news outlets. Social media have displaced print and broadcast to dominate the Chinese news industry. Weibo, China’s version of Twitter, and micromessaging service WeChat have brought a degree of freedom of speech and freedom of association, emphatically replacing the stringently regulated traditional media and becoming the main battleground of social discourse.

Sociologist Max Weber defined power as the ability to compel obedience, even against the wills of others. Some may suggest that power is the same as brute force, but this is incorrect; a ruler can achieve complete dominion without violence, simply by controlling the flow of information. The Chinese government’s monopoly on power can be represented by four objects: a gun, money, handcuffs and a pen. The gun and handcuffs show domination by force, while the pen and cash symbolize the rule of information. At times, all four elements may work in combination. The Chinese Communist Party (CCP) may still be in firm possession of the gun, handcuffs and money, but the Chinese people themselves are increasingly wielding the pen.

Information about the murder of British businessman Neil Heywood—for which Gu Kailai, wife of former Politburo member Bo Xilai, was convicted, while Bo himself remains under investigation for corruption—emanated entirely from sources other than traditional media. This was an important turning point. As the case of Bo Xilai shows, the gathering, dissemination, collation and analysis of news now takes place through processes completely different from those of traditional media, repeatedly breaching existing limitations on free speech in the process. In a desert of information, it is essential to gather information and professional knowledge through the Internet, piecing together a picture of each sensitive incident like a mosaic.

Thanks to this news mosaic, the CCP will find it impossible to proceed with its repressive reforms. Controlling information will not be easy either. Yet many officials simply have no understanding of what transparency entails and even less comprehension of how the times are changing. To prove this point, I used Weibo to denounce Liu Tienan, the deputy chairman of the National Development and Reform Commission and head of the energy board, for corruption, using concrete action to warn Party officials that a new era has arrived.

My hometown in the south of China is a mountain village so remote that the Japanese never reached it during World War II, and neither do Party newspapers and newsletters. But after I denounced Liu Tienan, more than 10 people in my village registered for Weibo and WeChat accounts. This is the might of technology.

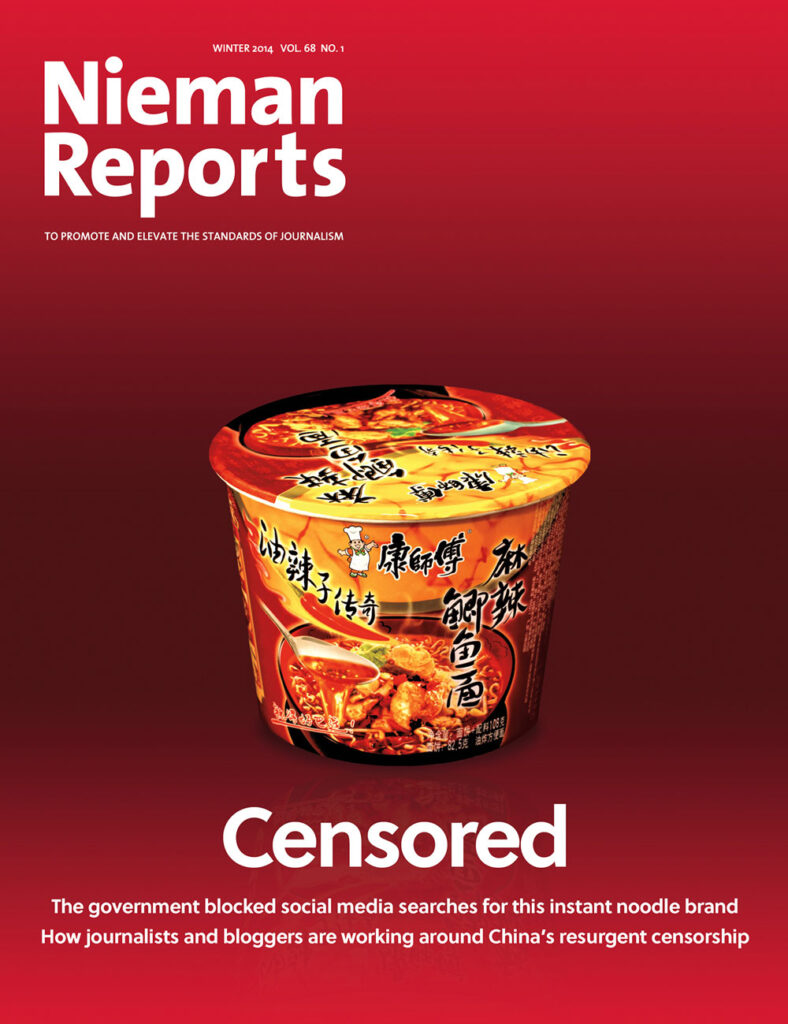

Nonetheless, those in power have not given up their dreams of controlling information. Instead, they have initiated the work of “cleansing” the Internet, attacking influential Weibo personalities, and arresting journalists. While this does have the effect of restricting and punishing the distribution of false information, it replaces the regular channels of the rule of law with administrative supervision. In fact, Weibo and WeChat themselves possess the tools to police their own content. The CCP’s reform plans both encourage innovation and restrict thought, thus creating a paradox. Lacking a free marketplace of ideas, China does not have the ability to renew itself or ensure long-term competitiveness. The prerequisite to creating such a marketplace is to smash the monopoly of information held by the state.

Luo Changping, a former deputy editor of Caijing Magazine in Beijing, won Transparency International’s Integrity Award in 2013