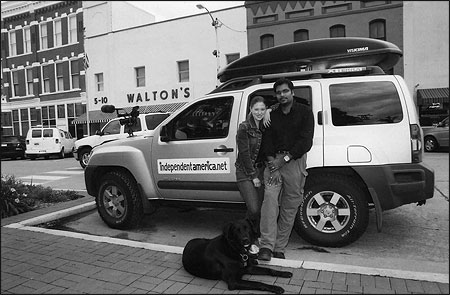

Filmmakers Hanson Hosein and Heather Hughes took their dog Miles with them on the road to make “Independent America: The Two-Lane Search for Mom & Pop.” Photo by Paul Perrier.

Six years ago I turned away from my television career with NBC News. Around me, I was seeing the explosion of broadband Internet access, powerful computer processors, cheap digital storage, and the proliferation of portable content creation and distribution devices. All of this was throwing the very controlled communication system that provided my work and income into turmoil. Suddenly almost everyone had access to a cheap and easy-to-use digital communication medium.

Yet the reality is still that humans have only so much time and interest in consuming media. When virtually everyone can produce content, the challenge becomes convincing people to pay attention and effect a transaction—share the content, get involved, or act in some way on what’s been learned.

Early in 2005, blogging was hitting a critical mass. High-definition cameras were descending to consumer-level prices, and new multimedia distribution platforms were proliferating. (YouTube launched that year.) As a novice filmmaker, I figured this was the right moment to combine the timeless art of storytelling with 21st century digital tools by making a film about a civic issue of growing concern. Could I build a community with trust at its core through such an effort? I didn’t know, but I wanted to try.

The film’s topic was the displacement of Main Street’s commerce and community by soulless big box stores—massive structures enticing people away from the core of their towns along stretches of road with a corporate shopping experience at the end. So my wife, my dog, and I set out on a cross-country trip, one in which we vowed to stay off interstates and away from corporate chain stores. As I conceived our story—it would be portrayed as a personal journey—these constraints would serve mostly as a headline gimmick; by the time our film, “Independent America: The Two-Lane Search for Mom & Pop” was ready for broadcast, the journalist inside of me realized that these two “rules” gave us an ideal storytelling structure and actually were our story.

In his “Poetics,” Aristotle observed what we now consider obvious; every story has a beginning, middle and end. He likened structure to the tightening of a knot—lay out the premise at the outset, then twist it tighter into a complication until a transformation (the climax) occurs. This leads to the denouement, literally the untying of complication—a release of the story’s tension. Here is where storytellers (and filmmakers) will often let the audience off the hook with an emotional release.

Our Brains: Emotion and Decision

The emotional element turns out to be crucial, since it actually helps us make decisions. In “How We Decide,” Jonah Lehrer observed that the right side of our brain allows us to see what we would otherwise fail to notice with our rational hemisphere on the left. “These wise yet inexplicable feelings are an essential part of the decision-making process. Even when we think we know nothing, our brains know something. That’s what our feelings are trying to tell us,” Lehrer writes.

What this means to us, as journalists, is that in competing for attention in an information-saturated society, we want people to make decisions based on what we communicate to them. It’s important to know the value and potential use we can make of emotional impact. In “Independent America,” there is mounting tension toward the middle of the film about whether we’d complete the journey. (We did.) As the end of the film approaches, we present viewers with an epiphany about Americans’ growing mistrust of large, powerful institutions. This happens as we encounter a community-supported department store in Wyoming that offers an alternative to the destruction of community that we’d seen before.

Aristotle’s enduring formula would predict that our mid-story tension followed by this final release would satisfy our story’s audience. In fact, what we offered as a return on their investment of attention and time was an emotional bond—in this case, empathy. And through this we managed to build trust and form community. We came to be regarded as credible storytellers who might be able to re-engage an audience in the future.

Establishing Trust: Then and Now

Stories are encoded within our DNA as humans. Joseph Campbell spent his life studying myths that have emerged from many cultures. In doing so, he discovered a universal pattern that transcends both culture and history. He called it the “hero’s journey”—the story of when a seemingly ordinary person reluctantly accepts a call to action, leaves behind the status quo, and embarks on a journey that entails trials and tribulations from which this hero learns valuable lessons. Ultimately he undergoes a transformation for better or for worse and returns home a changed person. Jesus, Moses, Mohammed, Harry Potter, Luke Skywalker, Frodo—these are all legendary personalities who have undertaken the hero’s journey.

Campbell believed that our love and belief in these myths originates from experiences we have as human beings who are born, live and die, and that each of us pursues his own hero’s journey, with a clear beginning, middle and end and a transformation along the way. Thus, inherently we grasp these three stages deep within ourselves. Indeed, we spend our lives trying to come to terms with it, so it’s no wonder that disparate societies can tell the same stories over and over again with different names, places and details. Yet we continue to be deeply attracted to these archetypal tales.

Certainly advertisers and public relations professionals apply Campbell and Aristotle in their marketing campaigns, sometimes even serializing them like a television drama. But until very recently these have been 20th century mass media products of passive, one-way, filter-then-publish media distribution. There we used to sit, without choice, as commercials played. By and large, we trusted what was said, in part, because the words and images reached us as they did. We ascribed credibility to organizations based, in part, on the huge resources and effort they deployed to reach us; those high barriers to entry must count for something, we figured, if only by winnowing out losers and charlatans.

EDITOR'S NOTE

Hosein elaborates on these themes in the slideshow “The Storytelling Uprising.”With digital media, barriers to entry are eroded. Old metrics for credibility and trust no longer guide us, nor does trust emanate exclusively from the power of a brand name or from the overpowering resources of a recognized institution. Through social networks, we adopt ways of trusting people we’ve never met, often based on identifying a mutual interest or point of agreement. When we find these, they encourage us to open a channel of communication. If we inject that channel with story, authenticity and a certain amount of emotion, we have laid the groundwork for an ongoing relationship of credible communication.

Back in 2005, in addition to the digital tools at our disposal, we had another powerful asset: a nascent relationship with the grassroots American Independent Business Alliance (AMIBA). As I contemplated documenting our journey, I called upon AMIBA to help drive their members to our blog. This simple request for a partnership of sorts was why we succeeded. Not only did engaging AMIBA members help shape the content of the story, but with them we built up a large amount of social capital. Before the end of our trip, members of AMIBA were clamoring for a DVD of the film so they could buy it and screen it in their communities. They hoped to convince neighbors and city officials to reform economic policy as it affected local retail.

We tapped into power by appealing to a niche community with the passion and focus to support the issues and ideas that “Independent America” championed. We didn’t start out believing that this was a story that would capture the attention and stir the energy of a mass audience. The good news for us was that the mass audience, like mass media, was already dividing into digital communities of interest. So it seemed natural, as well, to abandon the veneer of journalistic objectivity—a blunting of the editorial edges to appeal to a mass audience without offending them—given that we were already relegated to the populist sidelines.

Still we wondered how we might reach a wider audience. Despite our leanings in favor of Main Street, as a journalist I also wanted our portrayal of the issues to be fair and not dogmatic. Ditto with our conclusions. Along the way, we made our editorial practices transparent in blog posts and our mission statement. And such transparency—and striving for fairness—led us to an unexpected interview with Wal-Mart officials. Wal-Mart receives 800 interview requests each week; they granted us an interview even though we didn’t even have a distributor for the film because, they told us, they were impressed by our professionalism and independence.

After our film was made, we found that we could break out of our niche community to reach a much broader-based audience. We did this by connection to a wide mix of digital communications streams, broadcasting the film internationally, and receiving high-profile exposure on Yahoo! and Hulu.

Somewhere between the monopolistic, hierarchic and centralized mass media outlets of the 20th century and the atomistic, anarchic and decentralized nature of citizen production and distribution lies the sweet spot, a place between institution and amateur, between left and right brain. The influence of these media creators comes not from any institution, but from their own personal brand—trust built through ongoing storytelling and the curation of knowledge within a community.

Hanson Hosein is the director of the Master of Communication in Digital Media program at the University of Washington, a filmmaker, and a former NBC News correspondent and producer. He is working on a book about storytelling in the digital age.