All illustrations by Mark Fiore

Just great. My first foray into book reviewing is reviewing a book by Victor Navasky, former editor and publisher of The Nation, onetime editor at The New York Times Magazine and once a columnist for The New York Times Book Review. So I’ll be reviewing the reviewer, passing judgment on the editor, and critiquing the publisher. On second thought, maybe this is the perfect assignment for a cartoonist …

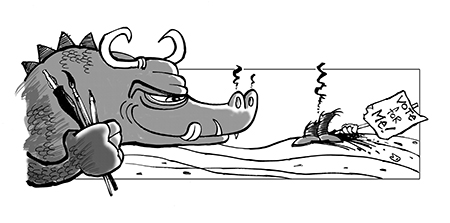

It is generally accepted, particularly by Navasky (see fig. A), that political cartoonists are allowed to be a pain in the ass. Whew.

“The Art of Controversy: Political Cartoons and Their Enduring Power” is Navasky’s love letter to the art of political cartooning. This is a very well researched love letter, mind you, one that attempts to explain the power of political cartoons. As Navasky establishes in the introduction: “So far from being a definitive history, what follows is an inquiry into how cartoons and caricatures get their power and their ability to make a difference.”

Navasky details three theories—the cartoon as content, image and stimulus—that explain why political cartoons can cause people to act, engage, become enraged, riot and even kill. While reading about his theories was fascinating, I’ve been trying to wipe them from my brain ever since. I am a creator of political cartoons more than a consumer of them and fear that if I know too much, the magic of creation may disappear. Irrational, I know, but I don’t think Dumbo would have ever flown if he had known the exact composition of his “magic” feather from the start. This is much more a reflection of me and my twisted brain than of Navasky’s theories about political cartoons, but when passion gets explained, it loses some passion. I have delusions of being like B.B. King: I can’t read music; I just play the notes.

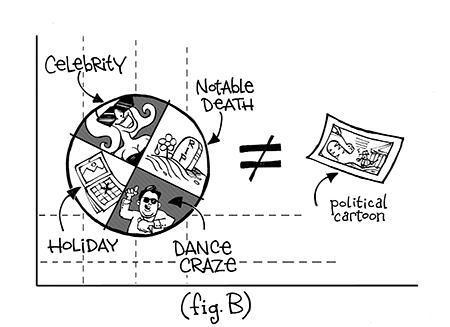

The best political cartoons are created when the cartoonist gets angry. This is why one of my favorite lines from “The Art of Controversy” is one of the simplest. From Navasky’s Ten Cartoon Commandments, or “Propositions” as he calls them: “Proposition Number One: The political cartoon, with or without words, is an argument.” The statement seems so simple and obvious, and it permeates the very essence of nearly every cartoon in the book. Yet, sadly, many of today’s “political” cartoons do not follow this commandment at all. Thanks to Navasky’s detailed exploration of the power of political cartoons, we can see the weakness of many of today’s cartoons that claim to be political. A celebrity combined with an upcoming holiday does not a political cartoon make (see fig. B). Navasky’s Proposition Number One should be etched in the drawing board of every political cartoonist.

Some may question Navasky’s choice of cartoonists represented in the book’s gallery. I found myself asking these questions as well. The stupendously amazing caricaturist Al Hirschfeld in a book about political cartoons but no Pat Oliphant? I think this is due in part to the fact that Navasky devotes an enormous amount of attention to caricature and seems to elevate caricature higher than all other facets of political cartooning. Additionally, that bastion of political cartooning (um, or at least stipple portraiture), The Wall Street Journal in its review took issue with the fact that some great modern day political cartoonists were left out.

While I would have loved to see more of my talented beer-drinking cartoonist buddies represented, the author makes no attempt to hide the fact that his work leaves things out. “I have also not dealt here with the power of comic strips, animation, television, moving pictures, new visual technologies, and the latest apps,” Navasky explains. “But if one picture is worth ten thousand words, and a journey of a thousand miles begins with a single step, then consider these words that step, and think about it as you ponder the cartoons on the pages that follow.”

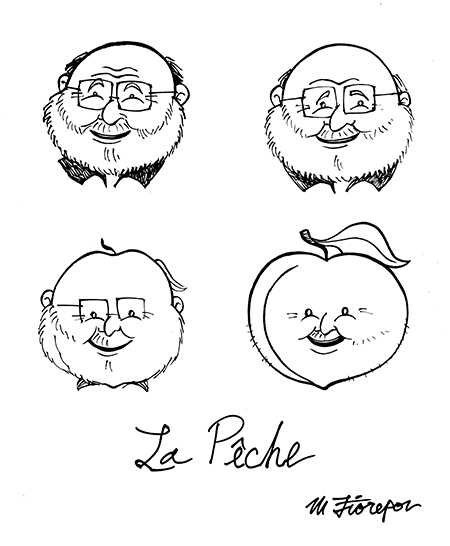

Much of “The Art of Controversy” reminded me of riding in a car with a good friend on a long road trip. You both have similar interests and likes; he reminds you of your shared, long lost cartoonist friends like William Hogarth and Herblock; and, boy, he really is a true believer in absolute free speech. Wait, did he just call for that Nazi cartoonist Fips to be killed? Amazing, he’s got the actual testimony Charles Philipon gave when he was on trial for his famous “La Poire” cartoon, which depicted King Louis Philippe as a piece of fruit! Wow, now he’s talking about giving Edward Sorel a place to crash. I wonder what he thinks about ... Whoops, we’ve got to stop and get gas.

Detailing the power of the political cartoon is motivating to cartoonists and enlightening to everyone. I hope Navasky’s love of political cartooning is infectious and spreads to editors and readers across the globe. This is a great conversation and a road trip I’d like to continue.

Mark Fiore is a Pulitzer Prize-winning political cartoonist who creates political animation in San Francisco. His work has appeared on the San Francisco Chronicle’s SFGate.com, BillMoyers.com, Newsweek.com and MotherJones.com. Before turning to animation, his political cartoons appeared in The Washington Post and the Los Angeles Times, among other papers.