Photo by Alejandra Villa.

"Oh, you’re the one who speaks Spanish.” I was at a farewell party for a coworker at the (New York) Daily News and had just been introduced to one of our investigative reporters. These were the first words he spoke to me.

My beat at the Daily News, the fourth largest metropolitan daily in the country, is covering Brooklyn schools. In my four years at the paper, I also have covered changes wrought by the 1996 immigration law, economic development in various commercial strips of Brooklyn, hurricanes and earthquakes, plebiscite votes in the Caribbean and Central America, as well as my share of crime, politics and the usual neighborhood complaints.

I thought amassing such a variety of clips was enough to establish my credentials as an average and sometimes, I hoped, above average reporter. But once again this chance meeting with another reporter reminded me that even if there was no malice involved in the assumption, colleagues still thought the main—maybe the only—asset I bring to the paper is my language skills. It turned out that this reporter was looking for help on a story on sweatshops. “A lot of the workers only speak Spanish, and I’m just not getting the depth of detail I could if I were interviewing them in Spanish,” he told me.

I nodded, waiting for the part where I would be told that my knowledge of communities such as Sunset Park and Corona, where there are a lot of fly-by-night, windowless assembly factories, would be an important contribution I could make to this project. Instead, I was told about how a Chinese-speaking library aide had already been drafted to help with interviews, but there was no Spanish-speaking equivalent.

I politely declined, citing a heavy workload in my beat, and instead suggested using community-based organizations that work with sweatshop workers both as translators and as go-betweens. “It might help you not just with the language issue, but with the trust issue,” I said. “To be honest with you, if I was a possibly undocumented worker I wouldn’t be able to tell the difference between you and an INS agent, and I might not be the most forthcoming.”

Some of my friends inside and outside the paper later suggested that I should have become involved with the project and injected concerns and issues that the main reporter might have overlooked. For example, I’d want to explore how Korean or Israeli managers communicate with Spanish-speaking or Chinese-speaking workers.

The punchy, old-time tabloid style of the Daily News affects not only the way we write, but also the way we interview people. For most man-on-the street interviews, or the average interview with a victim’s family, commonsense politeness and language skills acquired in a first-year Spanish college class usually suffice.

But there are qualities other than language skills that influence how well stories can be reported. For example, my own schooling, both in private school in the Caribbean and in public school in New York, informs my reporting about education more deeply than if I simply understood the words of Spanish-speaking parents. I know that for immigrant Latino parents, uniforms are a fact, not an issue worth debating. I recognize that for many recent arrivals, teachers and principals still retain the aura these positions hold in many of our home cities, towns and rural communities, where they are among the most educated professionals, and are therefore respected and unquestioned.

For many immigrant parents, a school system that encourages—almost requires—them to assume an aggressive, at times confrontational, position toward the people in charge of their children’s education is a foreign concept. This discomfort contributes often to their lack of involvement in parents’ associations. I also know from my experiences, those of my siblings, and those of my immigrant friends that attitudes toward bilingual education are not necessarily shaped by a parent’s thorough knowledge of the historical conditions and civil rights struggle that created the programs that are under attack.

Despite having plenty of education stories to report, I am still asked to “pitch in” on breaking stories on Latinos and on Latin America—especially natural disasters and elections. While this sometimes challenges my time management skills, I am happy to do it. I would not for anything trade the two nights I spent last May jetting between the upper Manhattan headquarters of two of the three major Dominican parties during presidential elections on the island. Livery cab drivers, stylists in beauty parlors, and corner store owners were so wired following the vote that that other presidential election in November paled in comparison. As one of only six Latino staffers—three reporters, two columnists, and one editor—on the news side, I am accustomed to getting calls from editors and fellow reporters asking for help. Often, I am asked for sources and for guidance on topics such as the changing demographics of Jackson Heights, a Queens neighborhood that is among the most diverse in the city. Or a reporter might want to know the ingredients in a Colombian arepa, or why merengue singer Fernandito Villalona might receive a standing ovation in an after-game concert on Dominican Day at Shea Stadium.

I know also that editors working on deadline might not always have time to ask me or another Latino staffer to fact-check details on every story involving Latinos. So between meeting my own deadlines, I try to keep tabs on major Latino-related stories and put in quick calls to correct minor but important mistakes in spelling, geography or cultural details. I know that other Latinos on staff take on similar unofficial copyediting duties, because even if our bylines are not on those stories, we know that Spanish speakers will often scan the paper for our names and call us when they are unhappy with any story in the paper.

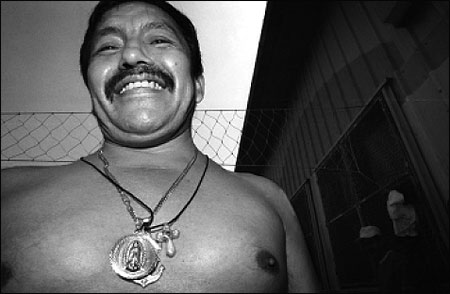

My familiarity with the cultures, socioeconomic factors, and histories of Latino communities in the city and country gave me an edge over other staffers on two big stories in particular. One story came as a Saturday morning call from an editor that sounded like the setup to a joke in very poor taste. As I rubbed sleep out of my eyes, all I could pick out were the words “55 deaf-mute Mexicans in slavery in Queens,” and I was off. The men, women and children crammed into two small houses in Corona had been recruited at deaf schools in Mexico, smuggled into the United States, and put to work selling key rings on the subway.

Ironically, my language skills were useless in speaking with these immigrants, who could only communicate in sign language. However, familiarity with smuggling routes and being able to quickly figure out which places the sellers might frequent was invaluable in the first hours of the story. I was not the only reporter on the story—all our Latino troops were deployed on it, some for weeks at a time—but I was more familiar than most with immigration from Mexico, a relatively recent phenomenon in New York City.

Having that knowledge was a major reason I was asked to work with the paper’s immigration reporter on a series on the Mexican community in New York, one of the more enjoyable experiences I have had here. We spent two months pounding the pavement, documenting the burgeoning Mexican presence in all boroughs and the ways their settlement and community-forming processes were similar to and different from those of other Latino immigrant groups. In effect, we introduced our readers to the restaurant workers, house cleaners, and flower sellers everyone could see but did not know.

I speak Spanish better than many reporters, but the language in which I have greatest fluency is the language of cultural subtext and background. It is this language, not Spanish, that allows me to better tell the stories of Latino lives, and telling better stories is what we are all trying to do.

Photo by Alejandra Villa.

Carolina González is the Brooklyn education reporter at the (New York) Daily News.