One of my favorite trips to Iran was in December 2001. A post 9/11 glow mellowed Iranian attitudes toward the United States, and politicians who previously would not have openly advocated normal ties said the time had come for the United States and Iran to end three decades of hostility.

Iranians, accustomed to being on the receiving end of terrible violence during the Iran-Iraq war, deeply sympathized with Americans, who had also been the victims of an attack by Arabs. There were spontaneous candlelit demonstrations on the streets of Tehran. The Islamic government suspended the ritual chants of “death of America” at Friday prayers and went so far as to provide tacit cooperation with the United States against what was, for a change, a mutual enemy: the Taliban regime in Afghanistan.

I returned to Washington and wrote a cover story for USA Today, in my role then as the paper’s senior diplomatic reporter, about the new mood in Tehran. It was symbolized, I thought, by the fact that Tehranis at restaurants all over the capital were guzzling Coca Cola—the real thing, not some Persian knockoff. Coca Cola had just opened a bottling plant in the eastern city of Mashhad, a harbinger, it seemed, of reconciliation with the United States.

I felt certain that I would be back in Iran within a year. But I couldn’t get a visa for more than three years. It is possible that I was a casualty of the downturn in relations that followed President George W. Bush’s decision in 2002 to put Iran on a so-called “axis of evil” with Saddam Hussein’s Iraq and North Korea. Or perhaps the reason was personal. Among the half dozen stories I had written off the 2001 trip was one about Reza Pahlavi, the son of the late shah. Even though I reported that many Iranians thought the “baby shah,” as they called him, was no solution for Iran’s political problems, the mere fact that I had devoted an entire story to the topic had apparently rubbed some Iranian security types the wrong way.

The challenges of writing about Iran for a U.S. reporter are myriad. In some respects, Iranian Americans face greater danger because they must go to Iran on Iranian passports since the regime refuses to let them enter as EDITOR'S NOTE:

Azadeh Moaveni wrote about her obligation to report regularly to "minders" in her 2009 book, “Honeymoon in Tehran: Two Years of Love and Danger in Iran.”Americans. That opens them to the prospect of de facto house arrest—should the government decide to confiscate their passports—or outright imprisonment as alleged subversives seeking the “soft overthrow” of the Iranian government. This happened earlier this year to Roxana Saberi, a freelance reporter for National Public Radio. Even those who escape such punishment are obliged to report regularly to Iranian “minders,” as has been documented by Azadeh Moaveni, a former reporter in Iran for Time magazine. That can lead to a certain amount of self-censorship.

So far, non-Iranian American journalists have had an easier time—perhaps because the regime doesn’t consider us so much of a threat. But challenges remain, the first being that of access to a country that has had no diplomatic ties with the United States for nearly three decades.

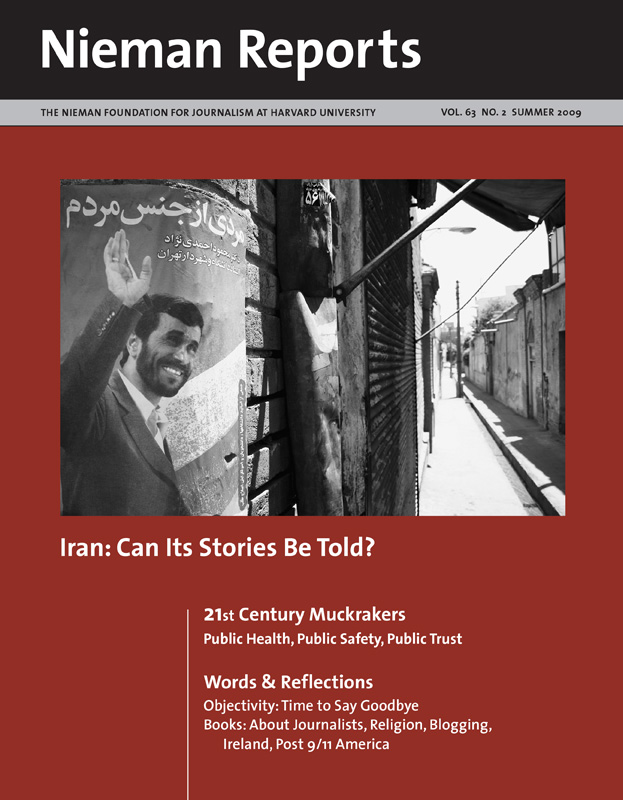

I have been fortunate to obtain seven visas in the past 13 years but learned with my Reza Pahlavi story that there are no guarantees. Gatekeepers change and new fixers can be required to smooth one’s path. The Iranian government sometimes appears to favor U.S. reporters with little knowledge of the country who might be more amenable to spin, although that has not happened in my case. In fact, it seems as though my access to officials has improved over time. It was on my fifth trip to Iran that I got my first big interviews—with then-national security adviser Hassan Rowhani and former president Ali Akbar Hashemi Rafsanjani. These interviews took a lot of preparation and vetting by people close to these top officials. To get the Rafsanjani interview, I first had to meet a diplomat close to the former president, one of Rafsanjani’s sons, and a brother. I was also asked to extend my visit by several days. Top-level interviews in Iran invariably come at the last possible minute, often literally hours before getting on the plane to go home. So it was when I interviewed President Mahmoud Ahmadinejad in 2006.

These interviews have provided fascinating glimpses into Iranian politics and decision-making. What keeps me going back to Iran, however, are the encounters with ordinary Iranians, from shopkeepers in south Tehran, to journalists, human rights activists, economists and young people out for a walk in the Alborz Mountains. Iranians are usually welcoming to Americans and surprisingly candid about their views. People make appointments and keep them—unlike their neighbors in some Arab countries—and there is a hunger to show that Iran and Iranians are better than their government and worthy of U.S. respect.

While I have not had a formal minder on trips to Iran, I assume that my driver and translator are obliged to report on what I do and whom I see. So I act in a way that is open and above board to cause the fewest problems possible for my Iranian employees as well as those I interview. I try to conduct myself with dignity and humility and to never lose my temper with Iranians, especially not about things that they cannot control.

The result so far has been reporting that keeps adding depth to my knowledge of a country that is increasingly influential in its region but deeply conflicted at home. The Iran I have come to know has the most complicated and interesting politics in the Middle East, the best educated young people outside Israel, and a surprisingly sophisticated understanding of the Western world. It is a place where the odds of someone shooting at you are relatively small, the food is delicious, and hotel rooms have wireless Internet and satellite TV. The downside, as a woman, of having to wear a headscarf and modest clothing is a small burden to bear in return for the chance to report on this dynamic nation.

When I decided in 2006 to turn some of my experiences into a book, I discovered in my notebooks from prior trips to Iran a significant amount of detail and color that had not found its way into my articles for USA Today or had appeared in truncated form. I was also fortunate to obtain a fellowship from the Woodrow Wilson International Center for Scholars that gave me time to write and to fill in the blanks in my narrative. In writing “Bitter Friends, Bosom Enemies: Iran, the U.S. and the Twisted Path to Confrontation,” I welcomed the opportunity to flesh out this material and produce something of more lasting value than a newspaper story. I wanted to educate Americans about Iran and the missed opportunities for improved relations during the past decade.

Delving deeper into the complex history of Iranian-American relations, I tried to break through the misperceptions long held by people in both nations; I did this, in part, by showing that even supposedly hard-line groups in Iran, such as the Revolutionary Guards, are not monolithic, with some influential members and veterans advocating ties with the United States. I also showed that a substantial number of Iranian clerics oppose the system of theocratic rule. At the same time, I portrayed the success of government security forces in repressing popular dissent and suggested that those in Washington who thought they could bring about regime change in the near future were not being terribly realistic. In explaining Iran and the failure of previous U.S. efforts to improve relations, I hoped to inform Americans so that policymakers could avoid mistakes and citizens could better evaluate U.S. policy going forward.

In my new role, as an assistant managing editor at The Washington Times, I have sought to cover Iran and U.S. policy both directly and indirectly. I’m invited to meetings with Iranian leaders when they visit the United States, have recruited stringers in Iran, and also try to augment the work of my staff reporters by maintaining contacts with U.S. policymakers and other experts. I also hope to be able to return to Iran, perhaps after their presidential election in June. Given the Obama administration’s stated goal of resolving the conflict with Iran through diplomacy, while not ruling out coercive measures, this topic is likely to—and should—remain on the front pages of U.S. newspapers for some time to come.

Barbara Slavin is assistant managing editor for world and national security of The Washington Times and the author of “Bitter Friends, Bosom Enemies: Iran, the U.S., and the Twisted Path to Confrontation,” published by St. Martin’s Press, 2007.

Iranians, accustomed to being on the receiving end of terrible violence during the Iran-Iraq war, deeply sympathized with Americans, who had also been the victims of an attack by Arabs. There were spontaneous candlelit demonstrations on the streets of Tehran. The Islamic government suspended the ritual chants of “death of America” at Friday prayers and went so far as to provide tacit cooperation with the United States against what was, for a change, a mutual enemy: the Taliban regime in Afghanistan.

I returned to Washington and wrote a cover story for USA Today, in my role then as the paper’s senior diplomatic reporter, about the new mood in Tehran. It was symbolized, I thought, by the fact that Tehranis at restaurants all over the capital were guzzling Coca Cola—the real thing, not some Persian knockoff. Coca Cola had just opened a bottling plant in the eastern city of Mashhad, a harbinger, it seemed, of reconciliation with the United States.

I felt certain that I would be back in Iran within a year. But I couldn’t get a visa for more than three years. It is possible that I was a casualty of the downturn in relations that followed President George W. Bush’s decision in 2002 to put Iran on a so-called “axis of evil” with Saddam Hussein’s Iraq and North Korea. Or perhaps the reason was personal. Among the half dozen stories I had written off the 2001 trip was one about Reza Pahlavi, the son of the late shah. Even though I reported that many Iranians thought the “baby shah,” as they called him, was no solution for Iran’s political problems, the mere fact that I had devoted an entire story to the topic had apparently rubbed some Iranian security types the wrong way.

The challenges of writing about Iran for a U.S. reporter are myriad. In some respects, Iranian Americans face greater danger because they must go to Iran on Iranian passports since the regime refuses to let them enter as EDITOR'S NOTE:

Azadeh Moaveni wrote about her obligation to report regularly to "minders" in her 2009 book, “Honeymoon in Tehran: Two Years of Love and Danger in Iran.”Americans. That opens them to the prospect of de facto house arrest—should the government decide to confiscate their passports—or outright imprisonment as alleged subversives seeking the “soft overthrow” of the Iranian government. This happened earlier this year to Roxana Saberi, a freelance reporter for National Public Radio. Even those who escape such punishment are obliged to report regularly to Iranian “minders,” as has been documented by Azadeh Moaveni, a former reporter in Iran for Time magazine. That can lead to a certain amount of self-censorship.

So far, non-Iranian American journalists have had an easier time—perhaps because the regime doesn’t consider us so much of a threat. But challenges remain, the first being that of access to a country that has had no diplomatic ties with the United States for nearly three decades.

I have been fortunate to obtain seven visas in the past 13 years but learned with my Reza Pahlavi story that there are no guarantees. Gatekeepers change and new fixers can be required to smooth one’s path. The Iranian government sometimes appears to favor U.S. reporters with little knowledge of the country who might be more amenable to spin, although that has not happened in my case. In fact, it seems as though my access to officials has improved over time. It was on my fifth trip to Iran that I got my first big interviews—with then-national security adviser Hassan Rowhani and former president Ali Akbar Hashemi Rafsanjani. These interviews took a lot of preparation and vetting by people close to these top officials. To get the Rafsanjani interview, I first had to meet a diplomat close to the former president, one of Rafsanjani’s sons, and a brother. I was also asked to extend my visit by several days. Top-level interviews in Iran invariably come at the last possible minute, often literally hours before getting on the plane to go home. So it was when I interviewed President Mahmoud Ahmadinejad in 2006.

These interviews have provided fascinating glimpses into Iranian politics and decision-making. What keeps me going back to Iran, however, are the encounters with ordinary Iranians, from shopkeepers in south Tehran, to journalists, human rights activists, economists and young people out for a walk in the Alborz Mountains. Iranians are usually welcoming to Americans and surprisingly candid about their views. People make appointments and keep them—unlike their neighbors in some Arab countries—and there is a hunger to show that Iran and Iranians are better than their government and worthy of U.S. respect.

While I have not had a formal minder on trips to Iran, I assume that my driver and translator are obliged to report on what I do and whom I see. So I act in a way that is open and above board to cause the fewest problems possible for my Iranian employees as well as those I interview. I try to conduct myself with dignity and humility and to never lose my temper with Iranians, especially not about things that they cannot control.

The result so far has been reporting that keeps adding depth to my knowledge of a country that is increasingly influential in its region but deeply conflicted at home. The Iran I have come to know has the most complicated and interesting politics in the Middle East, the best educated young people outside Israel, and a surprisingly sophisticated understanding of the Western world. It is a place where the odds of someone shooting at you are relatively small, the food is delicious, and hotel rooms have wireless Internet and satellite TV. The downside, as a woman, of having to wear a headscarf and modest clothing is a small burden to bear in return for the chance to report on this dynamic nation.

When I decided in 2006 to turn some of my experiences into a book, I discovered in my notebooks from prior trips to Iran a significant amount of detail and color that had not found its way into my articles for USA Today or had appeared in truncated form. I was also fortunate to obtain a fellowship from the Woodrow Wilson International Center for Scholars that gave me time to write and to fill in the blanks in my narrative. In writing “Bitter Friends, Bosom Enemies: Iran, the U.S. and the Twisted Path to Confrontation,” I welcomed the opportunity to flesh out this material and produce something of more lasting value than a newspaper story. I wanted to educate Americans about Iran and the missed opportunities for improved relations during the past decade.

Delving deeper into the complex history of Iranian-American relations, I tried to break through the misperceptions long held by people in both nations; I did this, in part, by showing that even supposedly hard-line groups in Iran, such as the Revolutionary Guards, are not monolithic, with some influential members and veterans advocating ties with the United States. I also showed that a substantial number of Iranian clerics oppose the system of theocratic rule. At the same time, I portrayed the success of government security forces in repressing popular dissent and suggested that those in Washington who thought they could bring about regime change in the near future were not being terribly realistic. In explaining Iran and the failure of previous U.S. efforts to improve relations, I hoped to inform Americans so that policymakers could avoid mistakes and citizens could better evaluate U.S. policy going forward.

In my new role, as an assistant managing editor at The Washington Times, I have sought to cover Iran and U.S. policy both directly and indirectly. I’m invited to meetings with Iranian leaders when they visit the United States, have recruited stringers in Iran, and also try to augment the work of my staff reporters by maintaining contacts with U.S. policymakers and other experts. I also hope to be able to return to Iran, perhaps after their presidential election in June. Given the Obama administration’s stated goal of resolving the conflict with Iran through diplomacy, while not ruling out coercive measures, this topic is likely to—and should—remain on the front pages of U.S. newspapers for some time to come.

Barbara Slavin is assistant managing editor for world and national security of The Washington Times and the author of “Bitter Friends, Bosom Enemies: Iran, the U.S., and the Twisted Path to Confrontation,” published by St. Martin’s Press, 2007.