In 1985 I encountered a book unlike anything I had ever read. “Common Ground” by J. Anthony Lukas, NF ’69, took a critical issue—race relations—and told the story in the most unforgettable of ways.

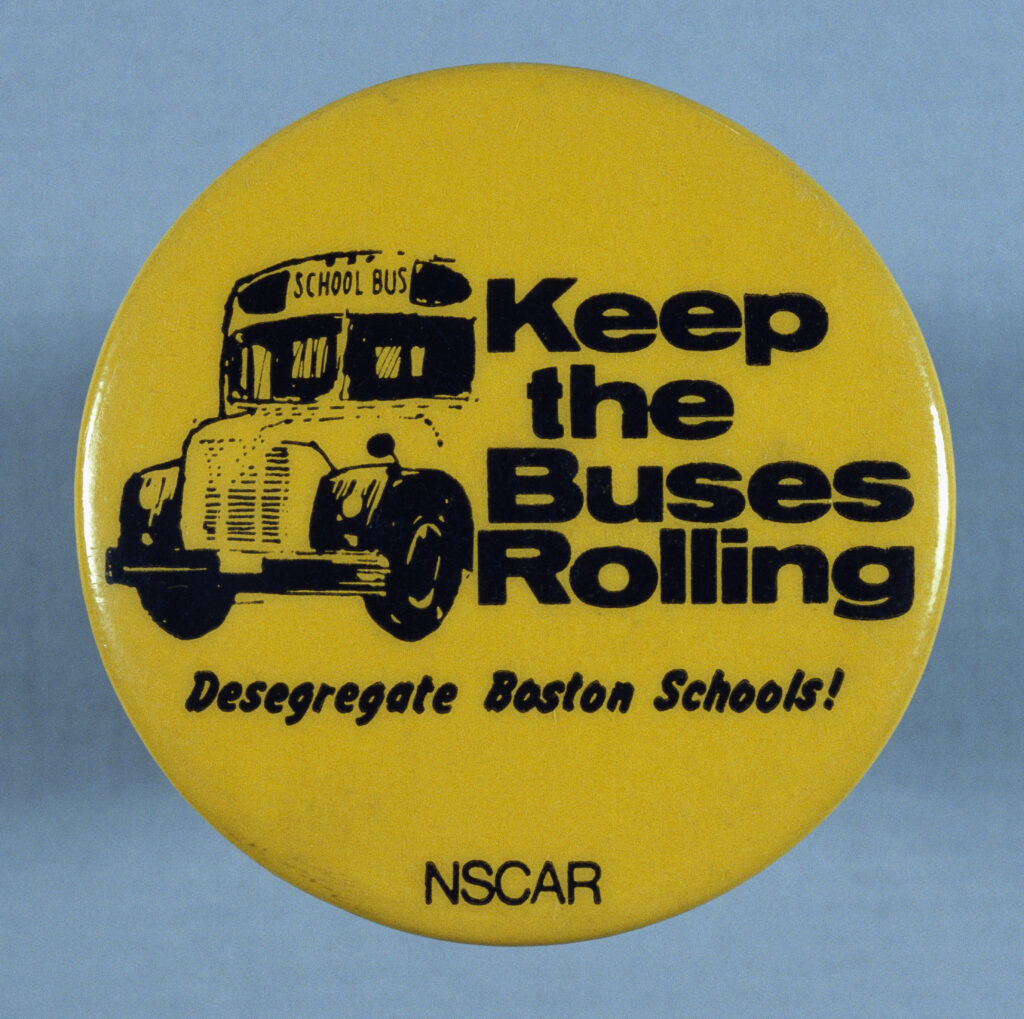

Lukas identified three families and reported how court-ordered busing to integrate the Boston public schools affected them. Step by step, he reported the decisions of city officials and judges that led to the busing order and then the impact, step by step, on an African-American family, an Irish-American family, and a liberal Protestant family.

The dramatic story told much about who we are as a people, and how we see “others.” On the day the busing ordered by U.S. District Judge W. Arthur Garrity was to begin in 1974, thousands of protestors showed up on Boston Common, pelting U.S. Senator Edward Kennedy with tomatoes and eggs when he sought to calm tensions.

Lukas was part of the wave of journalists that, as Tom Wolfe documented in “The New Journalism,” helped push reporters away from the stifled formal reliance on press conferences and official pronouncements, from the reporter as stenographer to something much more.

Common Ground: A Turbulent Decade in the Lives of Three American Families

By J. Anthony Lukas

Alfred A. Knopf, 1985

Excerpt

George, whose street name was Sly, and his brother Richard, known as Snake, had been out on Prescott Street, playing stickball against the factory wall, when a little kid had come by with a transistor radio, chanting in a monotone, “Dr. King is dead, Dr. King is dead.” At first the brothers jeered, “Get out of here, you little bugger,” and lashed the ball harder and higher against the concrete. But when the kid stuck the radio in their faces they heard it too. Although they were only twelve and fourteen, they knew enough about Martin Luther King to feel an acute sense of loss.

Their mother, Rachel Twymon, wept when she heard the news in her apartment on Prescott Street in Orchard Park. When her eight-year-old daughter, Cassandra, said, “Ma, he wasn’t a member of our family, so why are you crying?” she replied, “Because, Cassandra, what he got killed for makes him my big brother, because he wanted all of us to be equal.” She started to tell Cassandra that there were other reasons why she felt particularly close to King, reasons that went back fifteen years to the days she had known the young theological student they called Martin. But her recollections were interrupted by a knock on the door as two policemen from District 9 appeared to tell her, “They’re breaking into your store, Mrs. Twymon. You better get on down there.”

Excerpt from “Chapter 2: Twymon” from COMMON GROUND by J. Anthony Lukas, copyright © 1985 by J. Anthony Lukas. Used by permission of Alfred A. Knopf, an imprint of the Knopf Doubleday Publishing Group, a division of Penguin Random House LLC. All rights reserved. Any third party use of this material, outside of this publication, is prohibited. Interested parties must apply directly to Penguin Random House for permission.