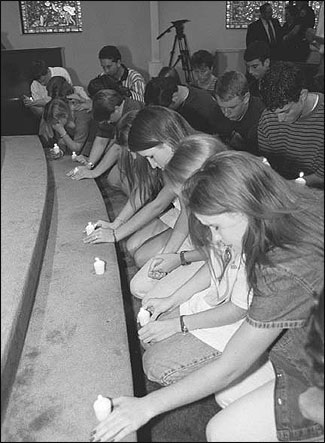

Pearl High School students pay homage to their fallen classmates during a candlelight memorial service held at Paul Truitt Memorial Baptist Church. Photo by Vickie King/The Clarion-Ledger.

Reports of shootings at some inner-city schools in Jackson, Mississippi, while not commonplace, are not totally unexpected. Violence pervades many of the neighborhoods around the schools. So it’s reasonable to assume that violence will occasionally invade the schools near them.

What shocked Mississippians about the October 1, 1997 shootings at Pearl High School was the community in which it occurred. Largely white, heavily Christian, predominantly conservative and politically Republican. A community not given to gang activity, which is what the public normally associates with violence.

When the shooting occurred, it became an empty-the-newsroom, devote-all-available-resources situation. Whoever got there first and got the most information about what happened would write the main story. As it turned out, it was a police reporter and the higher education reporter. The latter, Andy Kanengiser, was sent because he lives in Pearl and drove to the scene not knowing if his son, Elijah, might have been among those shot.

Reporters who would have been the first chosen to head to the scene because of their experience in covering this kind of story were not immediately available. They were brought in several days later to report follow-up stories that explored more deeply the “conspiracy” prosecutors were alleging.

Our coverage did not come up lacking for the reporters we did utilize. One of the benefits and burdens of a smaller newsroom is that you have reporters capable of doing anything assigned to them—and who volunteer to help even when not called upon. Among them, on this story, were our legislative reporters and feature staff.

The result was the most complete report on what happened of any newspaper or television news team that covered it. It was so complete and the follow-up so extensive that a half dozen calls daily came in from other news operations—from New York to California, from London and Ireland—with requests to interview our reporters.

Teams of two editors were assigned to oversee various aspects of the story. For example, one team handled stories about the killings and law enforcement response. Another team focused on stories on reaction from the community, parents, students, church leaders and legislators. Two others focused on developing profiles of the suspect, Luke Woodham, and the victims, as well as organizing a look at past incidents of teen violence and clues to a troubled youth. A former metro editor, now in editorial, was called in to do quality control of our entire package of stories, making sure all names, ages, place references and times were accurate.

In a mass meeting held on the first day of the story, reporters were given the complete list of stories and instructed that if they obtained information that would fit another story better than their own to pass it along to the appropriate reporter.

The coverage naturally involved photography and graphics, which were part of the planning process. We had to decide what photo was most appropriate to which story. People on staff who had children in the school helped us to get yearbook photos of some of the students and to provide a layout of the school’s commons area to show graphically where the shooting occurred and step by step what happened.

Reporters had been dispatched to the school, the police department, the hospitals, the sheriff’s office, and finally to the suspect’s home, when his identity became known. By then, of course, police had found the body of Woodham’s mother, Mary Woodham. She had been stabbed to death and bludgeoned.

As editors and reporters, we respond immediately and intensely to breaking news. But working for a newspaper as opposed to television news allows us more time for deliberation. We knew the allegations of Satanism’s role in the shootings, but we were not prepared to sensationalize the story with tales of devil worshipping. Our caution was justified. Luke Woodham’s manifesto, as it turned out, had more to do with Nietzsche than with Satan. And Luke Woodham’s problems had more to do with a feeling of inadequacy and ostracism than with devil worship.

Our subsequent coverage fell primarily to two reporters, Butch John and Mario Rossilli, both of whom are dogged diggers of information. John has done a plethora of stories examining teen violence, child abuse and the criminal justice system, stories that won a Silver Gavel Award. Rosselli previously covered the county where the shootings occurred and won a Robert F. Kennedy Journalism Award with groundbreaking work covering the state’s AIDS drug-funding crisis.

Those two reporters, along with the rest of our reporting staff, brought something more than their reporting expertise to the coverage of this horrible event. They brought restraint. They didn’t descend like news-hungry vultures, taking what they wanted and disappearing. They reported the news from a community, a bedroom community of Jackson, and did their jobs with a sense of responsibility that comes from being a part of a community. Effortlessly, it seemed at times, they walked that difficult line of persistence and respect. In doing so, John was able to secure interviews with the families of the two students killed. Now, a year later, he remains among only a handful of reporters to whom one of those families will talk. When other reporters chased the sister of that victim trying to get an interview, he stood back. And when he called the family later that day, it was not to get information; it was to make sure they were all okay.

Our reporters showed empathy and respect to the victims and their families, but they also handled their professional decisions with the kind of care not always evidenced by journalists today. They resisted the kind of sensationalism that was played up by other media when six more teenagers were arrested and charged with conspiracy in the case. Their restraint gave them a reporting edge, as well, with those teens’ attorneys and family members. It was not a situation in which they underreported the allegations; instead they placed them in the proper context of speculation. And when other breaking news shoved the story from the limelight, our reporters continued to follow it. They continued to ask how this could have happened and why and how it could have been prevented.

Now, one year after the shootings, we can reflect on how the city of Pearl and the school have changed. Both lost their innocence but have gained insight. Administrators there are not concentrating solely on security but on mentoring youth and getting parents more involved, on promoting inclusiveness and educating youth about how to prevent violence. Consequently we, too, are focusing more on these issues in ways we might not have before this tragedy occurred.

The only aspect of the story that remains not fully told is that of Mary Woodham. Who was she? In the telling of this story, she became a footnote: “…also killed was…” Her family did not—and does not—want to talk about her. Luke Woodham’s father remained an enigma and is unreachable. And so Mary Woodham disappeared into a journalistic footnote as the cell doors closed for life on her son.

Deborah Skipper is Metro Editor of The Clarion-Ledger in Jackson, Mississippi.