A friend of mine who lived in the village had arranged the interview. Nonetheless, when I sat down with my interlocutors—two men and a woman—there was tension in the air. I began by explaining that I aimed to write a story about the meaning that the hajj held for them, how they had interacted with Muslims from around the world, and how the rituals of the hajj served to connect them to Islamic history. But before I could get much further, one of the men spoke bluntly: "You're an American. So your image of Islam and Muslims must be negative."

I was taken aback but tried to maintain momentum. I explained that perhaps Americans were more in the dark about Islam than hostile to it; I offered that the perspectives of Islam to which I had been exposed while doing a master's in Middle Eastern studies had been anything but negative. Still, the hajjis remained skeptical and posed a pop quiz: Could I name the five pillars of Islam? The question was easy, and I answered it. By demonstrating that I knew something about my interview subjects' faith, which was at the root of the experience that I wanted them to share with my readers and me, I earned the privilege of their trust.

I am often reminded of this vignette, because it foreshadowed the considerable journalistic challenges in reporting on Islam and the Arab and Muslim worlds that would emerge more than a decade later and that remain apparent today. The seminal events of September 11, 2001 have had a profound and lasting effect on the American public's exposure to and understanding of Islam and Muslims and, for most Americans, the conduit of information has been the mainstream media. For the past six years, reports on Islam and other aspects of the Arab and Muslim worlds have appeared on a near-daily basis in print and broadcast media as U.S. engagement in the Middle East and South Asia has broadened and deepened.

Immediately after September 11th, journalists faced a steep learning curve in covering Islam and Muslims at home and abroad. Beyond reporting on the core beliefs and practices that Muslims share, making journalistic sense of the sheer diversity of Islam and the Muslim world has proved much more challenging. The lack of a central clerical authority in Islam, the differences between Sunnis and Shi'ites, and various customs prevalent in some parts of the Arab and Muslim worlds that are dictated by patriarchal social structures rather than by religion, per se, combine to make reporting on "what Muslims believe" and "what Islam says" on a wide range of topics (from women's roles in society to jihad) a complex undertaking. At least two other factors further complicate this journalistic task. Prior to 9/11, Islam and Muslims were unknown to most Americans because Muslims have not been as visible in American politics and popular culture as other minority groups and, after 9/11, the spate of reportage on Islam and Muslims was generated by the wholly negative context of those horrific events—events that neither represented nor were condoned by the vast majority of Muslims at home or abroad.

Studying What's Been Written—And What Hasn't

By the time of September 11th, I had moved from the realm of newsroom to that of academe, and the sheer volume of reporting on Islam and Muslims led me to create a seminar course called "Reporting the Arab and Muslim Worlds." In order to increase their media literacy and knowledge of topics including Islamic diversity, U.S. public diplomacy in the Arab and Muslim worlds, the concept of jihad, the role of women and the question of Palestine, students assess the strengths and weaknesses of U.S. mainstream reporting by juxtaposing journalism with academic writing while applying five criteria. These are:

- Balance: The range and mix of sources

- Point of view: From whose perspective/s the story is told?

- Voice: Who is quoted/who gets to speak?

- Context: Relevant historical, political and/or cultural factors

- Framing: Which issues are included and which are omitted?

The steady stream of U.S. mainstream media reporting on the Arab and Muslim worlds during the past six years has provided a wellspring of source material. It is a body of work that over time and across media has indicated mixed results—many of them positive—as several examples illustrate.

A masterful journalistic account of the Shi'ite majority in Iraq, which tackled historical complexities and diversity of perspectives from within that community, was reported by David Rieff in The New York Times Magazine in February 2004. In August 2004, the Los Angeles Times published "Muslims in Las Vegas," a five-part series by Peter H. King based on multiple reporting trips over a year's time that yielded an evocative portrait of a community whose members were rendered as three-dimensional human beings, secure in their Muslim identities against the backdrops of the quintessential American sin city and the often treacherous political climate in the wake of 9/11.

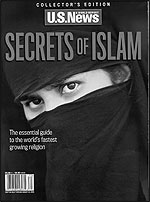

In the summer of 2005, U.S. News & World Report published a special collector's edition on Islam; its pieces on the tenets of the faith and its historical and cultural aspects were illuminating. However, its cover headline, "Secrets of Islam," and accompanying photograph (a woman's head peering out from behind a black veil) coupled with much of its interior photos and pieces on conflict between Muslim societies and the West, bore a distinct Orientalist tone. In April, New York Times reporter Andrea Elliott won the 2007 Pulitzer Prize for feature reporting for her three-part series "An Imam in America," a richly detailed portrait of an immigrant imam leading Muslim congregations based in and around New York City. Also this spring, the Chicago Tribune ran a front-page feature on Muslims' concerns over the certification of halal food, slaughtered and blessed according to Islamic law. Indeed, these examples show that in recent years, U.S. media coverage of the Arab and Muslim worlds has given voice and three-dimensionality to Muslims, their history and lived experiences.

REFERRED ARTICLE

"Muslims in America"

– Andrea Elliott

The Absence of Context

As a body of work over time and across platforms, however, the reporting still faces a major challenge of contextualizing the conflict between the Muslim world and the West (and in particular the United States). While this conflict is not only a function of Muslim actions and attitudes but also the result of U.S. policy and intervention in the Muslim world over the course of the last half-century, the reporting more often than not reflects the former while minimizing or excluding the latter.

This is evident in U.S. mainstream reporting from and/or about Iran, Israel/Palestine and Iraq (among other venues), which repeatedly imparts the details of conflict from a U.S. policy point of view but leaves important contextual questions unasked and unanswered. Reporting on the Iranian "nuclear crisis" tends to focus on potential threats posed by a nuclear Iran; left unaddressed are Iran's concerns for geostrategic parity in a region where the United States tolerates the nuclear capacities of its allies (India, Pakistan, Israel). Then there is the underreported fact that the U.S.-Iranian relationship was originally strained not by the taking of American hostages in 1979 but by the CIA-backed overthrow of the country's elected secular leader in 1953 and U.S. support for 25 years of oppressive rule by the shah.

Reporting on the Israeli-Palestinian conflict, whose 60th anniversary will be marked next year, rarely takes into account the pronounced effects that decades of U.S. military aid and diplomatic support for Israel have had on the trajectory of the conflict—in many ways making prospects for peace more distant (especially vis-ˆ-vis Israeli settlements). The tragic and bungled U.S. war in Iraq is reported daily via accounts of the horrifying violence and instability there and the escalating political battle at home between Congress and the White House; however, there is little if any attention paid to how a sustained American corporate and military presence in Iraq will affect its future long after most U.S. troops are withdrawn.

Incorporating balanced, critical treatment of these sensitive but crucial issues is the key challenge in reporting on the Arab and Muslim worlds today. The metaphor of my experience with the Palestinian hajjis more than a decade ago is instructive but cautionary. Getting the easy details right is important, but it is only the first step; seeing ourselves—our actions and their consequences—in the picture is much harder.

This means that the American public, and American journalists acting on its behalf in reporting on the Arab and Muslim worlds, must understand that the history of U.S. policy and intervention in these regions—from the beginning of the cold war until today—is intimately connected to how Muslims throughout the world regard and react to us. We need to understand that these policies are carried out in our name, and they shape Muslim perceptions not only of our government, but also of us (as citizens who freely elect it). Toward this end, the journalism must not only give voice to Muslim attitudes but also probe and contextualize historical and political facts upon which they are based.

Without this perspective, the reporting will remain incomplete and along with it Americans' understanding of a part of the world that is increasingly tied to our own interests and well being.

Marda Dunsky is a scholar and writer. She has worked as an editor and reporter at four newspapers, including the Chicago Tribune. She teaches "Reporting the Arab and Muslim Worlds" at DePaul University. Her book, "Pens and Swords: How the American Mainstream Media Report the Israeli-Palestinian Conflict," will be published by Columbia University Press in the fall.