My mother says she never meant to be a journalist. She did it because she was looking for a way to support her music passion.

“I didn’t have J-school swagger,” she recently told me. “[But] I could bullshit my way anywhere.”

It was the 1970s and she was living in New York City. She’d recently graduated from college as an English major with no practical skills and the feeling she was “teetering on the edge of a black hole.” The only thing she wanted was to be a professional viola player.

While scheming ways to make a music career, she looked for a more conventional job. She found a posting in The New York Times for a “teeny tiny” publishing house that had two partners and a bookkeeper.

“They wanted someone else, a body,” my mother said. “They put me down as an editorial associate on the masthead because they wanted bodies.”

In reality, she wasn’t just a body. She was a receptionist and did real work. But her use of the word “body” strikes me. This small magazine had enough resources to hire someone mostly to make their outfit look bigger — someone who had no training and expressed no enthusiasm for the trade.

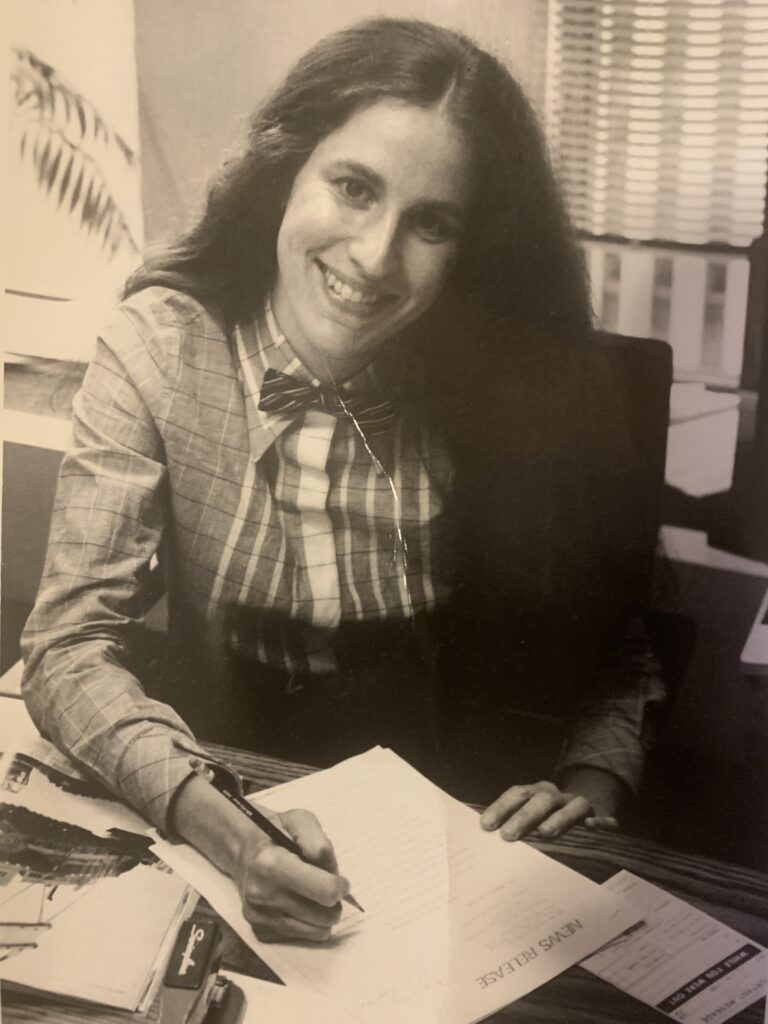

Now, my mom, Nadine Post, 74 (pictured left), is one of the best-known journalists in the construction industry. She just retired from a 52-year career, most of which was at the construction magazine Engineering News-Record, where she wrote roughly 4,000 stories, 300 of them cover stories for the print magazine. She’s earned countless awards for excellence in business-to-business journalism.

Juxtaposed with today’s media landscape, my mother’s entree into journalism is almost laughable. While she assures me that journalists have always worked extreme hours for little pay, and that part of her success was because she wasn’t picky or idealistic (which she says I am), there’s no question that conditions are worse for later generations. Today’s young reporters work for free, take on debt, endure mistrust and hatred on social media, and are expected to be experts in multimedia with their own unique brands — all for the best-case scenario of … a modest salary and a job that demands long hours? If we’re lucky.

Unlike my mother, most of us don’t become journalists to subsidize our passions. Journalism is the passion.

In my mid-30s, passion was my only reason for switching careers and entering the trade. At the time, I had a stable job and a reasonable salary at an environmental nonprofit. What I did best in that job was ask hard questions. But that wasn’t the job. I was the one whose head got stuck deep in New York State statute, intending to clarify one aspect of solar policy but going down a rabbit hole of philosophical questions about tax credits and policy design. I always wanted to go deeper, and I thought that as a journalist I’d have the time to. I also imagined I’d be like Erin Brockovich, sneaking around and extracting samples from vats of contaminated water.

I was able to follow my passion because I have savings and my family is fully behind this new direction. I remember calling my mom after a tearful conversation with a journalist peer who’d left the field because she couldn’t find a full-time job. I had just made the big decision to go to graduate school for journalism and was already discouraged. My mom said something like, “If it makes you happy, that’s the most important thing. The money will come.”

That remains to be seen. This is my second year out of graduate school, and I’m just approaching covering my living expenses. I’m an adjunct journalism professor with a contract renewed by semester, I’m a part-time editor, and I’m freelancing for a few outlets. If I have a child, I likely won’t have paid parental leave. My “salary” is cobbled together from part-time work — no predictability and no benefits.

The thing is, I don’t have it that bad. I now have two master’s degrees, so I could easily find other work. And I have parental support if I want to buy a house, which I could never do alone with my current assemblage of income.

But this arrangement should not be what’s required for new journalists to break into the industry. Journalism will never be the most lucrative field, but we live in a time when humanity’s actual survival depends on asking hard questions about climate change, on telling people’s stories who are often overlooked, and on reporting the truth. We can’t rely on exceptional scenarios to produce the journalists who will carry out this responsibility. It’s not fair to the hopeful journalists who have the passion, and it’s not fair to the public.

I decided to talk to my peers about their situations — people who, like me, had a belief that they could direct their minds, hearts, and storytelling skills toward something that might keep our crumbling democracy together. Each one has a particular set of conditions that make it possible, for now, to be a journalist. But hearing their stories, I’m glad I didn’t talk to them before I made my own decision.

They’re doubtful, discouraged, and debt-ridden. They’re working side jobs and living paycheck to paycheck. And what hurts the most is to hear some of them question whether there’s something wrong with them. Whether or not they have the right emotional constitution to be in journalism — work that they love, that they’re good at, and that we need so desperately.

These people represent the journalists-for-now. But at what cost? And for how long?

Lydia Larsen, 23

Freelance science journalist and baker

Madison, Wisconsin

Waking at 3:50 a.m. could be a reasonable way for a journalist to start their day. Perhaps they work the early shift at a 24-hour news channel. Perhaps they’re getting ready to fly overseas to cover a conflict. Or maybe they’re just on deadline.

But that’s not what Lydia Larsen’s alarm is for. She’s waking for her 5 a.m. shift at a bakery about 15 minutes’ walk from her apartment in Madison, Wisconsin, where she works three days a week to supplement her journalism income. Despite having a degree in science communication and two esteemed journalism fellowships under her belt — with the American Association for the Advancement of Science that placed her at Inside Climate News (ICN) and, more recently, with Sierra Magazine — she hasn’t found a full-time job.

“I don’t think I’ll ever really get used to the 3:50 a.m. alarm,” said Larsen. “That was a tough adjustment.”

The decision to work at the bakery came when she finished her first fellowship, with ICN. “[I was] staring into the abyss of unemployment, and I was like, ‘Oh my God, what do I do now?’

“If you look at my file of applications for jobs: deeply depressing. And I gave up on organizing it.”

She kept freelancing for ICN, along with other odd writing jobs. One was with an alumni magazine that paid fairly well. But she knew she needed a regular job — one that wouldn’t conflict with normal working hours.

“Obviously you can … read through documents whenever you want,” she said. “But when you need to interview people, usually that’s in business hours.”

A week after she started at the bakery, she went to the National Association of Science Writers conference, because she was still doing everything she could to advance her journalism career.

“I remember at a certain point between … the travel [and being] overwhelmed at a conference … I was like, ‘Damn, you’re delirious with exhaustion right now.’”

This year, she’s going to the conference again. “This job isn’t going to get better if I don’t network a bit,” she said, feeling the weight of still not having a full-time job.

"I just would really like to be in a world where ... I can make enough money to buy strawberries and not feel guilty about it. I’m just caught up in the day-to-day of my own survival.”

— Lydia Larsen, freelance journalist

She has already spent $600 on flights and registration, and will pay some more to split a hotel room with a friend. She’s taken on extra shifts at the bakery and upped her freelancing with the alumni magazine, which will “hopefully” allow her to cover the conference costs as well as other life expenses in the coming months.

Larsen doesn’t have debt, is on her parents’ health insurance for a few more years, and is “vibing” with her current roommate in an apartment in Madison. But if any of those conditions were different, she’d be in trouble.

It’s not like freelancing is all bad, but it comes at a cost.

“I can do whatever the hell I want,” said Larsen. “I can cover horseshoe crab-spotting one week and a constitutional amendment … the next. … But the constant anxiety of, ‘Okay, I’m pitching this now [and] if they accept it I should be getting this paycheck not this month, but next month … and if I need this much money to pay my bills’ — I don’t know how long I can live like that.”

For now, her dreams are simple. “This is really quaint, but I just would really like to be in a world where, I don’t know, I can make enough money to buy strawberries and not feel guilty about it,” she said. “I’m just caught up in the day-to-day of my own survival.”

Niya Doyle, 24

Consultant and aspiring beauty editor

Brooklyn, New York

In May, Niya Doyle wrote a piece for Editor & Publisher titled: “Is journalism just a rich kid’s hobby?”

“Who can survive on the $15–20 an hour a full-time internship might offer? Let alone perform free labor for publications that can’t afford to pay writers anything at all?” she wrote. “But without clips, you can’t grow in the field or eventually write for larger publications, which means bigger earning potential.”

It’s a dilemma Doyle feels acutely. She grew up in New Jersey with working-class parents who encouraged her to pursue whatever academic direction she chose, but she had to take out hefty private and federal loans to get through undergrad at Boston University. While in college, Doyle wrote for several campus publications, including Boston University’s Daily Free Press, Her Campus BU, and pop culture magazine Bee Buzz. But, as she learned more about the field, she felt the risk of not getting a reliable, salaried journalism job was too high.

“People who … [are] able to pursue journalism full time usually have some sort of support system, whether that’s parents helping them out or maybe they got a full ride,” Doyle said. “I know that journalists don’t actually get paid a lot and paid internships are few and far between. So I’m like, for my financial future, maybe journalism isn’t the greatest choice.”

To pay her bills, Doyle works as an associate producer at a digital consulting firm while freelancing — often for little to no pay — to build her portfolio. She writes about beauty and pop culture for publications like Autostraddle and Haloscope. In a recent article, she shed light on the limiting and potentially racially problematic nature of the “clean girl” makeup aesthetic, pointing out that “clean makeup implies there is dirty makeup” and celebrates the “Clean Girl-approved color palette.”

Despite knowing she would take a pay cut from her current salary of $70,000, Doyle still applies for entry-level journalism jobs from time to time but feels like her résumé “just goes into the void.”

Her current strategy: keep a foot in the field by freelancing, and when Craig Newmark Graduate School of Journalism at the City University of New York (hopefully) goes tuition-free in 2026, she’ll apply – if she doesn’t burn herself out before she gets there.

She’s not taking the barriers to entry personally, but she does think that having journalists with a range of identities makes journalism stronger.

“If the media industry wants to … hear stories from young people … if they want people of more diverse backgrounds,” she said, education has to be affordable and media executives have to stop “de-prioritizing our work.”

Sophie Park, 26

Freelance photojournalist

Cambridge, Massachusetts

By most measures, Sophie Park is succeeding as a freelance photojournalist. At 26, she has consistent work with outlets like The New York Times, The Washington Post, and The Wall Street Journal. This past year, she caught a moment when student protesters at MIT knocked over police barricades, snapped grizzly bears and their cubs in Alaska, and covered the Democratic and Republican national conventions. But despite these high-profile gigs, she doesn’t feel secure.

“It feels like I’m just always waiting for the other shoe to drop,” said Park, who remembered a tense day in December 2023 when she had three photo assignments across two states: a morning assignment at the Boston Tea Party Museum, a hospital in the early afternoon, and then a trip to New Hampshire, where Gov. Chris Sununu was expected to endorse Nikki Haley for president.

She’d said yes to everything, not because anyone was forcing her, but because the lifeblood of freelancers is their reputation with their editors, and editors like a freelancer whom they can call on easily.

“In fact, there’s even a saying amongst some freelancers that there’s no such thing as saying no,” she added.

Park got her first big break just a year out of college. One of her photojournalist friends had to pass on an assignment at The Washington Post, so she was introduced to an editor there. Her career took off after that. She now grosses up to $80,000 a year, which, after taxes, is enough to pay her half of a $2,600-per-month one-bedroom apartment she shares with her partner, who has a stable income. And she sees this, in some ways, as a success.

“It seems so unlikely that I have made it to this point where I’m sustaining myself as a freelance journalist in this economy,” she said.

But the grind of freelancing is draining on many levels. It’s traveling, maintaining her own collection of expensive equipment, buying her own health insurance, and putting expenses from gigs on her own credit card before getting reimbursed. It’s financial planning, which she does on a 12-column spreadsheet that tracks when she’ll get paid for each assignment. It’s “dealing with a million bosses,” living “in fear of losing a potential client all the time.” And she’s managing non-journalistic clients, who account for about 20 percent of her income.

“I still feel like I need to chase those corporate events and really build those other pillars of support and money … because you never know what one pillar might crumble.”

She said she feels lucky, especially given the current environment for freelancers, with day rates that generally do not keep up with inflation. But she would not be able to afford her apartment if she didn’t have a partner. She might want a child, but can’t imagine bringing another person into the mix with the mental load she’s carrying.

“I’m just really hard on myself. And I think most journalists are,” she said.

“It’s one thing to show up physically for an assignment. It’s another thing to really connect with who you’re photographing, to be situationally aware, to make good calls … [then] reporting, collaborating with a writer, managing communication with your editor.”

If she does decide to have kids, she’ll have to cut journalism gigs and up her commercial work, which pays twice as much for a shorter day.

“I feel like doing photojournalism has become this noble thing and really … it’s [only] this noble thing because you have to make all these sacrifices to do it,” she said. “[Or] maybe I’m just a snowflake. Maybe I’m asking too much.”

Abril Mulato Salinas, 39

Fact checker, reporter, editor

Mexico City, Mexico

Working three different jobs to pay rent, having health insurance only sometimes, and getting laid off when newsrooms shrank or collapsed were conditions that Abril Mulato Salinas was used to as a journalist in Mexico. But when she got a Mexico City-based position as a fact checker for The Associated Press in 2019, she thought that could change. She terminated her freelance projects and had about five years’ peace of mind. Then she got laid off.

“When I received my definite contract here in the AP, I decided to leave everything [else]. It was less money, obviously, but I … wanted to have a life,” she said. “The salary was good enough for me to have a good life.”

Mulato, who has been a journalist since 2007 and has worked for places such as NBC Telemundo and El País, expects journalism to have highs and lows. But the relief she felt at finding stability and a reasonable salary meant a lot. Losing that was awful.

“It’s sad to say this, but I’ve been through this before. … But I thought that because it was a company based in the U.S., and that it was a big company,” things might be different.

Last year, Mulato and her partner had decided they wanted to buy a house. But when she went to New York to visit the U.S.-based portion of her team, her boss told her they were going to close the Mexico office. She came back and told her partner, “We can’t do it. I mean, I’m not gonna be paying for something when I don’t have a stable job.”

She and her partner typically split their expenses evenly. This past year, he started covering more than half of the rent because of the months when Mulato had either no work or comparatively lower-paying jobs. Since January, she’s applied for more than 20 positions, and is relying on temporary gigs like her current contract writing stories for Turkish Radio and Television Corporation.

“When I stopped working at the AP, I had to look again for new clients, gigs,” she said. “The people that used to be at some media [outlets] weren’t there anymore. And it’s starting … fresh, and it was hard.”

Mulato made the decision to pursue journalism when she was 17, and when she did, her father said, “Te vas a morir de hambre” — “you’re going to die of hunger.” He joked that he would open up a grocery store for her as a backup plan. Mulato’s more realistic backup plan is working in communications, to which some of her struggling journalist peers have migrated.

Her father died this year after a life of working jobs that were not satisfying. But the work Mulato does fulfills her deeply, so she’s making sacrifices and plans to stick it out.

“I don’t want to do what my father did,” she said. “I’d rather be happy.”