A recent story in Nieman Reports explored a shift in journalism: the decline in use of the classic reporter’s notebook. As digital tools become more sophisticated, offering features like automatic transcription, cloud storage, and AI-assisted note-taking, spiral-bound notebooks risk fading into obsolescence.

In Tool of the Trade, writer Gabe Bullard, NF '15, examined how these top-wired notepads, long a symbol of on-the-ground reporting, are gradually being replaced by sleek, ever-connected digital devices.

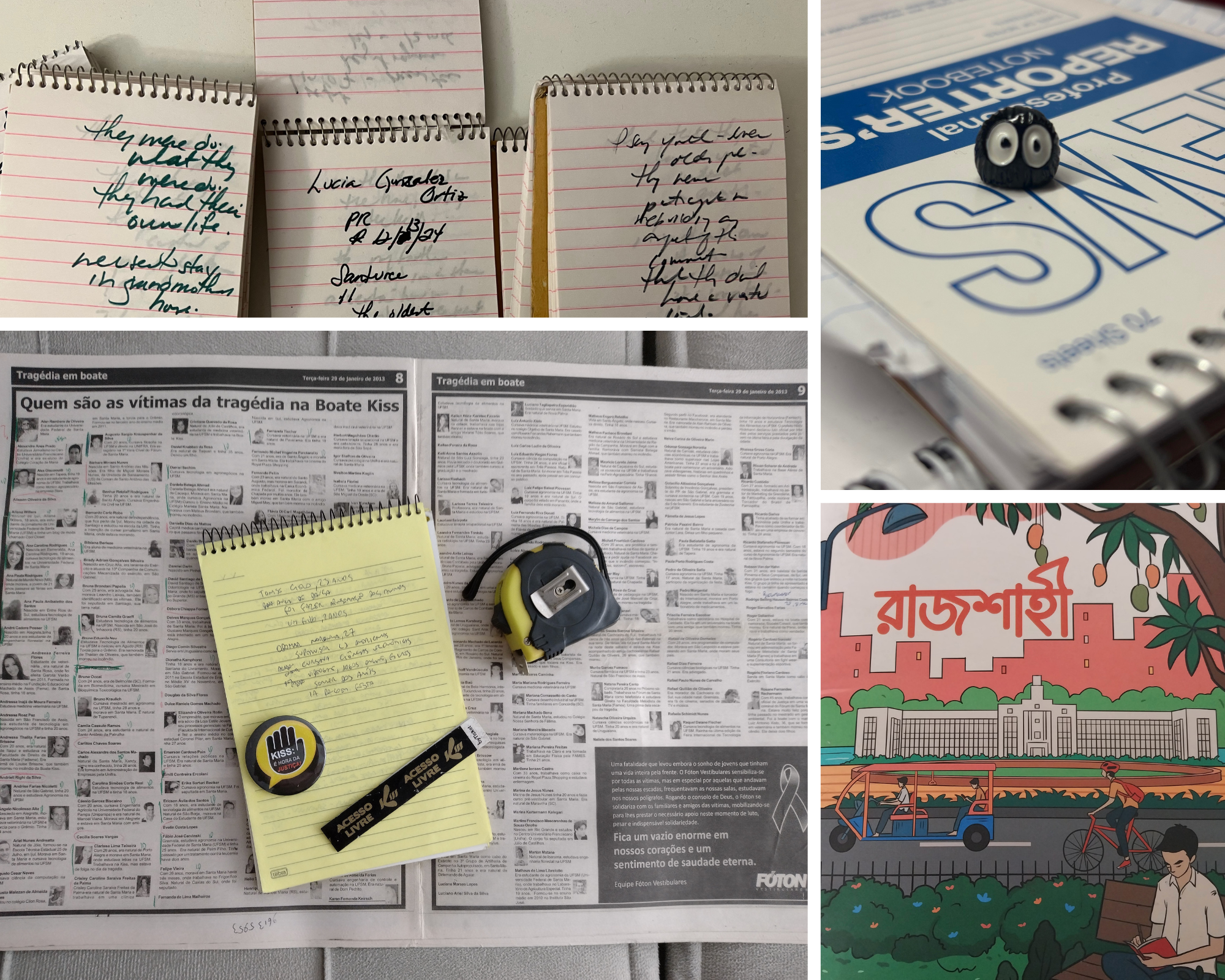

But we are not ready to write the notebook’s obituary just yet. In response to the piece, we put out a call to journalists asking if they still use a reporter’s notebook, and if so, what moments has it captured? The responses paint a picture of a tool that was a witness to history, a trusty repository of vital observations and, in at least one case, an archive of a romantic relationship.

A Rite of Passage

For many journalists, getting their first reporter’s notebook is a rite of passage. Robert Chaney, NF '20, is a staff writer for Mountain Journal where he covers the Greater Yellowstone region of the U.S. He had relied on the classic spiral-bound reporter’s notebook for years. But when he ventured into remote terrain on assignment, he realized it wasn’t ideal. "The red Mead Memo pad seemed perfect until it soaked up sweat on the trek into Akamina-Kishnina Provincial Park and the ink smeared," Chaney recalled. Eventually, he switched to the waterproof Rite in the Rain notebooks — one even survived a canoe flip. "Plus, they need pencils, which don’t freeze or leak."

Notebooks also can be deeply personal. AFP’s Dhaka Bureau Chief, Sheikh Sabiha Alam, NF '23, describes how flipping through old notebooks brings back memories of haunting interviews. One page, she found, contained a widow’s grief-stricken words: "Holding my newborn, I rushed to the hospital … they say his body was full of scars … my family prevented me from seeing him one last time." A few pages later, another interview — this time with a woman waiting for a loved one’s release from prison. "My diary, like poetry, holds ballads of both joy and sorrow," Alam said.

Process and Connection

Beyond invoking nostalgia, many journalists say their notebooks shape the way they work. Writing by hand forces clarity, helping distill a story as it happens. "Jotting notes slows me down just enough to really listen," said Saumya Singh, an associate multimedia news producer.

During an interview with an architect in Goa, Singh noticed how the act of handwriting surprised her subject. "He was shocked that a Gen-Z journalist still preferred traditional note-taking," she said. That moment turned into a deeper conversation about storytelling rooted in tradition. “I like to stick to notebooks because I feel I am more connected with the subjects whom I am interviewing. …I believe it gives them a sense of affirmation that I am attentive to what they are speaking,” Singh added.

Sarah Smith, a senior storyteller at the Houston Chronicle, believes her brain retains information better when she writes things down. "My hand connects to my mind by way of a pen or pencil. I won’t remember something I type, but writing on paper is like writing on my brain," Smith said. Her most treasured notebook isn’t even her own, it’s her husband’s from when he was a copy editor in 2019. "It holds the headline that first made him notice me, before we had ever spoken. Now, I keep it at my desk in lieu of wedding photos."

"The past, in ink"

Amy Jamieson had just one year of reporting experience when she asked her editor at People magazine to report on the events unfolding on Sept. 11, 2001. She made calls to Shanksville, PA, to find out anything she could about the tragic fate of Flight 93. “‘No survivors.’ I underlined those words — twice,” Jamieson said. “There’s spelling mistakes: ‘Shenkville.’ ‘Pitsburgh.’” Recently, she decided to digitize those records for her children. “It only took me 24 years,” she added.

For many journalists, notebooks aren’t just valued tools of the trade — they are irreplaceable records of history in the making. Jonathan Kapstein proudly shared his notes from reporting on the fall of the Berlin Wall in 1989. “Everywhere, worldwide, it was realized as the end of the … Cold War era that began 30 years earlier,” Kapstein wrote. “It also signaled the beginning of the next era that also lasted nearly 30 years: one of international integration.”

Michael F. Fitzgerald, editor-in-chief of Harvard Public Health magazine, still keeps a box of reporting notes from his 1994 trip to Taiwan, where he captured “the island as it was becoming a full-fledged democracy and a juggernaut in high-tech design and manufacturing.” “Other people have written that story, but I still can't get rid of this box,” Fitzgerald said.

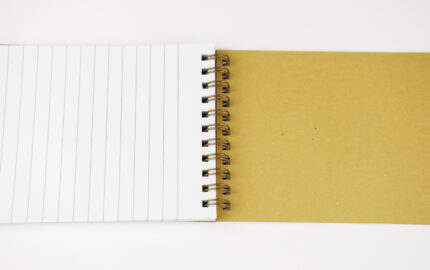

Nancy J. Guri Duncan, a writer and translator, has kept her notebooks from a two-year freelance reporting stint in India, where she had the opportunity to interview the Dalai Lama in the early ’70s. “Meeting that saintly man was one of the most memorable moments of my life. I still have the notebook where I wrote down his comments to me,” Duncan said.

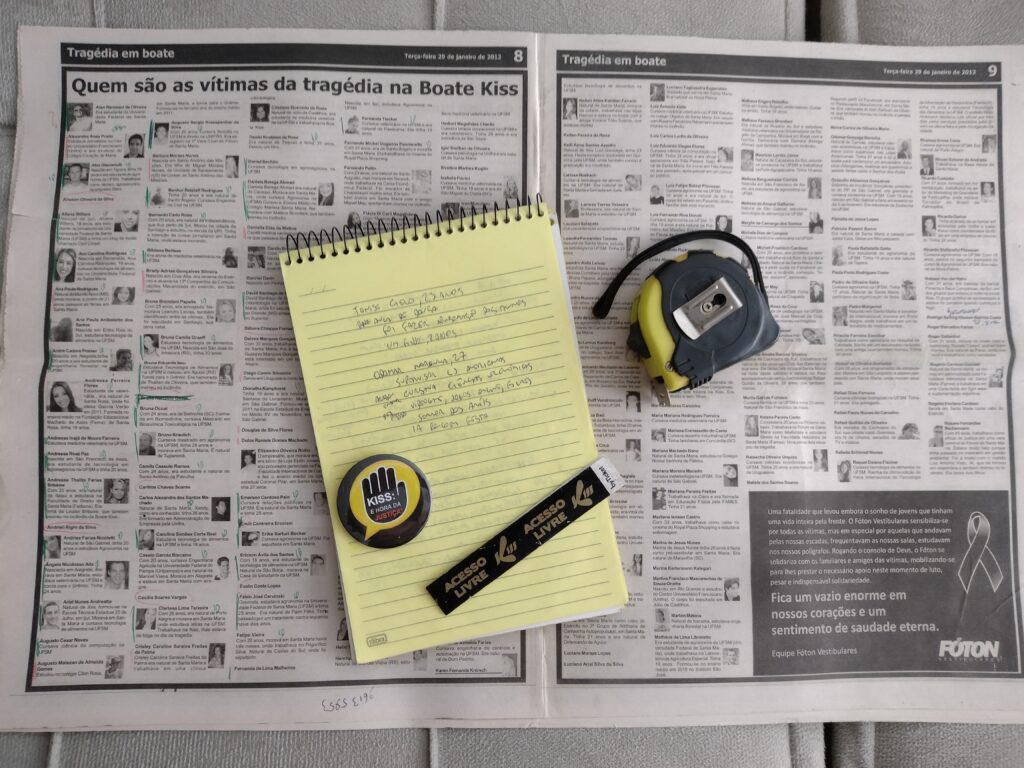

Technology is powerful, but it can have limitations, especially in the field. Marcelo Soares, founder and editor of the Brazilian data journalism outfit Lagom Data, recalls covering the 2013 Boate Kiss nightclub fire in Brazil in which more than 240 young people died. "I was the first reporter from a major media outlet to arrive at the scene,” Soares recalled. “The nightclub was still wet from the firefight, and there were shoes in the gutter, lost by the living and the dead." His yellow notebook holds sketches of victims' stories, gathered from grief-stricken families at a mass wake. Years later, he covered the trial of the nightclub’s owners, and one of the grieving relatives recognized her brother’s name in his notes. "I sent her a photo of my notebook," he said. "The past, in ink."

A Reflection of the Job

Despite the proliferation of digital tools, the reporter’s notebook persists as a symbol of the trade. "Everyone knows me as ‘the guy with the notebook,’" joked Tony Salazar, a sports journalist who finds a spiral pad easier to juggle than a phone in post-game interviews. The sight of a reporter scribbling in a notebook, he said, is still a recognizable image of the press at work.

Arlene Schulman, a journalist and book author, used dozens of them while embedded for two years in a Spanish Harlem police precinct for her book, “23rd Precinct: The Job”. "Sometimes, when cops and criminals spotted my notebooks, they were drawn to them, eager for their stories to be told," she recalled. "Others ran."

Ben Pu, a producer at NBC News, no longer actively uses a notebook, but he still holds onto the one he carried as a campaign embed during the 2020 presidential election. "It’s a great reminder of what I promised myself I would do for my career — and then achieved that dream."

Megan Cattel, Nieman Reports' assistant editor, contributed to the writing of this article.