In 2002, Mark Schleifstein and a team of reporters in New Orleans wrote “Washing Away,” a five-part series in The Times-Picayune that predicted the devastation of Hurricane Katrina three years later. When the series ran, the public was oblivious to experts’ fears that a major hurricane was likely to someday overcome the Big Easy’s levees. Using maps, illustrations, and other storytelling, the newspaper revealed how poor maintenance, erosion, and even burrowing semiaquatic rodents called nutria had weakened flood barriers in New Orleans, Jefferson Parish, and other areas Katrina would later hit hard.

“It’s only a matter of time before south Louisiana takes a direct hit from a major hurricane,” the introduction to the series said. “Billions have been spent to protect us, but we grow more vulnerable every day.”

The series triggered a short-lived conversation about Gulf Coast storm preparedness in New Orleans and Washington, D.C. that led the Army Corps of Engineers to look into preparing for bigger storms. Support for upgrades waned, however, as the War on Terror absorbed excess federal funding. The levees were left largely untouched.

“Did anybody listen? Yes and no,” says Schleifstein now. “The Army Corps of Engineers warned local leaders that the levees were too low. We reported on it all the way up to Katrina.”

When Katrina struck in 2005, the storm demonstrated that “Washing Away” was prescient—but also ignored by policymakers. In the wake of the deluge, the federal government spent $15 billion to repair New Orleans’ levees. The National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration has estimated that Katrina’s total cost was $81 billion.

Schleifstein won a Pulitzer for his reporting during Hurricane Katrina. “Washing Away” made him a hero among journalists for his foresight. (The New York Times called him “a prophet of Katrina’s wrath.”) Ask him about the origins of the series, however, and he’ll share that it took him four years to convince his editors to let him conduct the investigation. The scope of the story, the sheer devastation it foresaw, seemed outlandish to them at first. “The newspaper was not at all interested,” says Schleifstein. “What we’d be laying out is a conclusion that the entire city would flood, and we’d no longer have a newspaper.”

Now, after a steady diet of megastorms and other extreme weather—think Hurricane Sandy and the polar vortex—the attitudes of editors and the public at large are changing. Journalists who entertained the thought of widespread catastrophe might have appeared speculative and irresponsible in the past. Today, after Sandy flooded Lower Manhattan and two inches of snow shut down Atlanta, more journalists believe it’s irresponsible for the press not to ask whether extraordinary events could push disaster preparedness networks to their breaking points.

Inspired by the likelihood of future megastorms, earthquakes, and record-breaking droughts in an era when sea levels are rising and more people than ever, especially in the developing world, live in disaster-prone regions, journalists are increasingly pursuing a new model of reporting that investigates whether communities are prepared for looming calamities. Exemplified by work like “Washing Away”; “Concrete Risks,” the Los Angeles Times’s series last year on buildings vulnerable to earthquakes; and Paige St. John’s Pulitzer Prize-winning 2010 investigation into the undercapitalized Florida insurance industry for the Sarasota Herald-Tribune, the new approach collects the latest scientific data on credible worst-case disaster scenarios and asks whether buildings, bridges, hospitals, insurance policies, and other infrastructure are resilient enough to handle them.

“The traditional model is, something bad happens, then the reporter digs in and says, ‘They should have known about this or that,’ ” says Shelby Grad, city editor at the Los Angeles Times. “You see journalism looking now more at things before they happen.”

News audiences, who have become sophisticated consumers of disaster coverage in recent years, are ready for more in-depth journalism on the subject, according to a paper published recently by J. Brian Houston and Cathy Ellen Rosenholtz of the University of Missouri and Betty Pfefferbaum of the University of Oklahoma. Studying disaster news coverage between 2000 and 2010, the researchers found that reporting on tornadoes, floods, and similar events followed a familiar pattern of breaking news, cleanup and mourning, and, as recoveries wound down, fleeting political debates about readiness. Around a year later, the coverage ended.

The well-worn formula doesn’t address the full range of the audience’s questions about disasters, the scholars found. While readers’ and viewers’ attention ultimately drifts elsewhere, immediately after a disaster they especially want to hear as much as possible about the economic impacts of the event as well as how politicians handled the problems that arose. The researchers concluded that the time is ripe for journalists to address those concerns by considering writing about disasters before they strike, too. “Our results raise questions about the implications of such disaster coverage on wider political conversations about disaster-related issues, such as disaster aid, environmental protection, global climate change, or the costs of human development in areas prone to natural disasters,” Houston, Rosenholtz, and Pfefferbaum wrote.

The shift to inquiries that speculate about disasters comes as scientists are also increasingly sounding alarms about taking climate change and extreme environmental conditions into consideration when investing in homes, infrastructure, and other services. They’re urging journalists to portray the weather less as a destructive force, for instance, and more as a process that people must anticipate—or ignore at their peril.

The great challenge with stories about disaster resilience is psychology: The human mind is stubbornly oriented toward the short term and reluctant to acknowledge intangible dangers. “It’s called ‘personal optimistic bias,’ ” says Robert Meyer, a marketing professor and co-director of the Wharton Risk Management and Decision Processes Center at the University of Pennsylvania’s Wharton School. “It’s a belief that these things are going to happen but they aren’t going to happen to me personally. We’re not well-engineered to deal with low-probability, high-consequence events.”

Before Hurricane Sandy, for example, Meyer and his colleagues polled residents of coastal communities in Maryland, New Jersey, and New York, asking whether they had heeded repeated warnings about lengthy electricity shortages. Only 20 to 30 percent of those queried thought they would lose power for more than two days. Most prepared by picking up a flashlight and a few batteries and candles, a woefully inadequate response to a storm that wiped out entire neighborhoods. Few if any planned for the worst. “They were set for an event like a television event that would come this evening and tomorrow they’d be back to normal again,” says Meyer.

The human mind is stubbornly oriented toward the short term and reluctant to acknowledge intangible dangers

That shortsightedness is hard-wired. Behavioral scientists like Meyer distinguish between fast and slow thinking, a contrast popularized by Nobel Prize-winning economist Daniel Kahneman. Fast thinking, related to our automatic fight-or-flight response to emergencies, served humanity well in the past when we were struggling for survival as cave dwellers. Today, it helps us make life-saving snap decisions, like a sudden sharp turn to avoid a car collision. Slow thinking is a more reflective mode of thought used for planning, calculating costs and benefits, and understanding abstract concepts.

Most people think fast and slow throughout the day. But fast thinking is our default mode. Automatic and based on habit, it keeps us rooted in the here and now. For journalists, fast thinking’s shortsightedness has always been part of the challenge of gaining readers’ attention. But for those seeking to investigate infrastructure that might appear safe until a disaster strikes, it’s a hurdle to overcome. The problem to remember is that peoples’ tendency to ignore latent dangers doesn’t make those dangers go away.

“It’s a difficult proposition,” says the Sarasota Herald-Tribune’s St. John, who showed how small insurance companies in Florida were ill-prepared for widespread catastrophe. “But reporters can write about risk and remind readers of their denial. We build on a beach when the beach won’t be there in the future. The mortgage will be.”

Psychologist Paul Slovic, an expert on risk at the University of Oregon, uses seat belts to illustrate how slow thinking can overcome fast thinking. For years, only around 10% of drivers wore seat belts, even though everyone knew their chances of surviving a crash were substantially higher while wearing them. They were falling prey to fast thinking that didn’t see into the future. “People didn’t appreciate the cumulative nature of driving,” says Slovic. “On any one trip, the risk of an accident is one in 100,000. Sooner or later, you’re going to need a seat belt. You don’t get rewarded for buckling up until then, though, so it seems like a waste of time.”

Citing statistics, testimonials from injured drivers, aggrieved families, and other lobbying tactics—slow thinking that considers the big picture—advocates eventually persuaded state lawmakers around the country to enact laws forcing people to wear seat belts. Once they were part of drivers’ routines, strapping on a seat belt as soon as one sits in a car became a widespread behavior reinforced by fast thinking. The same dynamic occurred in the past with building codes and other safety regulations now taken for granted.

[Journalists'] watchdog role is as important as ever when it comes to protecting people from the pitfalls of fast thinking

If journalists can learn anything from behavioral science, it’s that their watchdog role is as important as ever when it comes to protecting people from the pitfalls of fast thinking. “If people are left to their own devices, people would effectively, unwittingly kill themselves,” says Meyer. “You need to save people from themselves. That’s where the role of the media comes in, to let people know that communities are facing risks they probably didn’t know about.”

To bypass fast thinking, Meyer and Slovic suggest journalists eschew statistics and scientists’ dry pronouncements. Instead, distill the science into examples that relate directly to individuals. That advice isn’t novel. Journalists have been “putting a human face” on statistics for years. In resilience investigations, the difference is that, rather than reporting solely on trends to date, reporters identify examples of misfortunes that could happen if trends continue on their current trajectory. “To do this ‘what if’ story right, you need to find the statistical models,” says Matt Waite, a Pulitzer Prize-winning reporter who teaches journalism at the University of Nebraska. “You have to be especially cautious about saying what could happen and how you frame the possibility that it would happen. You need to find that sweet spot of ‘Here is the most catastrophic thing that is most likely to occur.’ ”

Say reporters learn that engineers are worried that a large proportion of local school roofs are liable to collapse under extreme snowfall. They would pinpoint which schools, how many students they accommodate, how much snow those areas received in recent years, how much snow they’re forecast to receive in the upcoming winter, whether officials have the equipment to clear the snow, and so on. They might identify the schools on a map to convey the scope of the problem, use graphics to illustrate why heavy snowfall is a problem for particular roof designs, and discover if similarly designed roofs failed elsewhere and whether children were injured during those events.

The studies published every four years by the American Society of Civil Engineers are the counter example. The respected studies give American infrastructure dismal grades and generate press attention. But the perennial reminders of impending ruin have resulted in compassion fatigue among citizens who find it easier to slough off the amorphous, overwhelming necessity for infrastructure investments rather than tackle how to pay for improvements in their backyards.

Identifying a story doesn’t necessarily convince editors to approve it, of course. Andrew Revkin, who writes The New York Times’s Dot Earth Blog, which is dedicated to climate change and sustainable living, said he’s been slowly gaining ground in the years he’s been fighting to convince editors to pay more attention to resilience. “It’s wonky,” he says. “Just the word ‘infrastructure’ makes eyes glaze over in the newsroom.”

Revkin has learned to field questions from editors who have grilled him on stories and blog posts based on forecasts that seem to “get ahead of the news.” The bigger challenge, according to Revkin, is that preparedness stories often don’t have a clear conflict that makes them easy to present. There’s rarely a villain when infrastructure has been ignored for years while sea levels have risen incrementally and intense storms have grown more frequent. There’s nobody to blame if a disaster or tragedy has yet to occur.

Pittsburgh Post-Gazette transportation writer Jon Schmitz, who won an award from the American Society of Civil Engineers in 2012 for his infrastructure coverage, bypasses the dilemma by focusing on the economic impacts of inaction, often the straightest route to readers’ self-interest. “My approach to the job is not so much to warn people of imminent disaster,” says Schmitz. “I’m trying to get people aware of the cost of not addressing the problem. When a bridge collapses and you find yourself for 10 years taking a detour, what’s the impact on their wallet?”

That impact, if quantified, is one reason editors will publish these stories and people will read them. Irwin Redlener, director of the National Center for Disaster Preparedness at Columbia University’s Earth Institute, thinks economics should inspire the media to challenge the ways we take public spending for granted. After the September 11th attacks, the U.S. spent trillions on the war in Iraq and an anti-terrorism bureaucracy that many believe compromises civil liberties, Redlener says. Meanwhile, with millions out of work, a hurricane everyone knew would eventually hit the Northeast flooded Wall Street because of inadequate seawalls and other defenses. Journalists should report that juxtaposition, he argues: “We probably need something on the order of $3 trillion now [in infrastructure spending]. If you did that over 10 years, you’d get the benefits of an increase in resilience and a tremendous job machine. This is an issue that should be hammered by the press.”

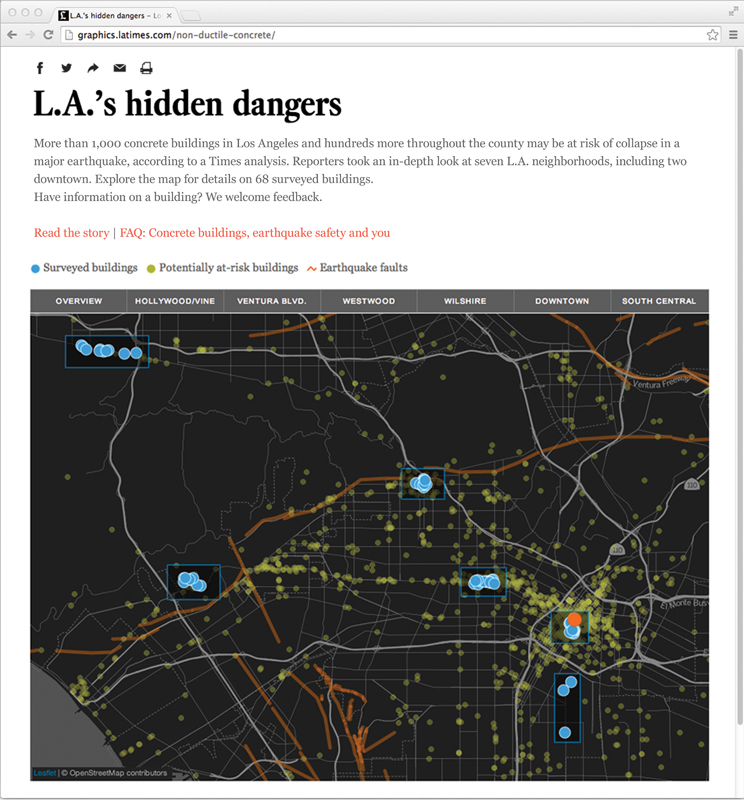

at risk of collapse in a major earthquake and provided detailed reports on 68 of them

The experience of Los Angeles Times reporters Rong-Gong Lin II, Rosanna Xia, and Doug Smith, who worked on “Concrete Risks” for two years, is telling. After two old concrete buildings collapsed during a deadly 2011 earthquake in New Zealand, the reporters wondered if similar tragedies could happen in Los Angeles. They discovered that University of California scientists had compiled a list of the same types of structures throughout the city, but wouldn’t release the data, arguing it was based on preliminary research. The reporters smelled a good story, but had to convince editors who weren’t interested in a speculative project that might serve only to frighten people. “It’s really hard to pitch a story when no one has died yet,” says Xia.

The existence of the unpublished university list, concern among other scientists, and the fact that California has been waiting decades for the Big One eventually changed the editors’ minds. Unable to obtain the university list, the reporters conducted their own analysis using the same criteria, studying county records to see which buildings in Los Angeles might contain the same flaws as those abroad. Then they walked the streets, inspecting buildings to make sure the records were accurate. They found that more than 1,000 buildings were at risk if and when a major earthquake struck.

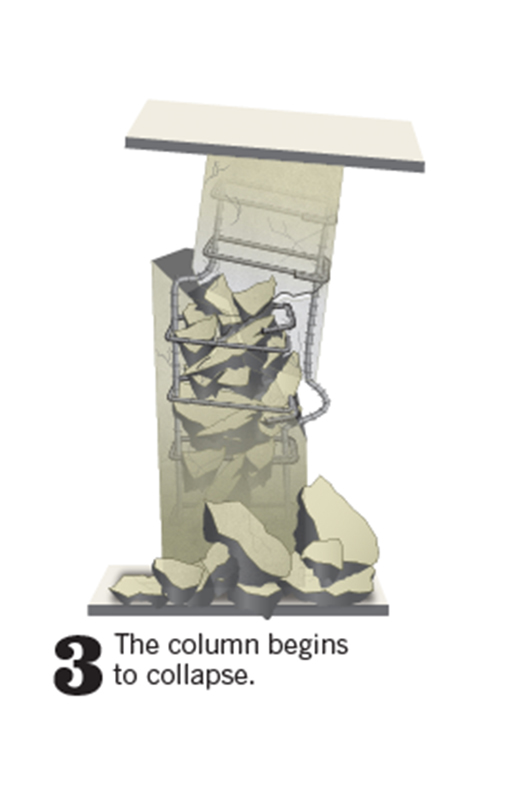

Published in October 2013, the project featured animated architectural graphics to demonstrate the weakness of the designs in question as well as online maps that pinpointed buildings. Building owners were given a chance to make comments on the online map to explain if they had retrofitted their properties.

The story acknowledges its limitations. Conservative estimates say as many as 50 buildings might collapse, and county records only suggest—they don’t prove—that the identified buildings featured risky designs. The reporters’ approach depended on scientific modeling that isn’t definitive yet nonetheless demonstrates the likelihood of certain outcomes. They needed to be clear that those outcomes were probable only under certain conditions, like a major earthquake that struck particular structures.

“Concrete Risks” helped precipitate change. After the story ran, city officials requested and received the University of California list, which identified 1,500 possibly problematic structures, and Los Angeles Mayor Eric Garcetti announced a partnership with the U.S. Geological Survey to better protect private buildings against earthquakes. A first step in that effort is to compile addresses of old concrete buildings.

Schleifstein is gratified that he’s helped prove journalists can responsibly warn readers about natural disasters. He still exudes a kind of survivor’s guilt, however, about his coverage of New Orleans’ disaster preparedness. He wishes he could have done more. Or, more accurately, he wishes people had acted on the problems he wrote about.

One of the Times-Picayune editors who initially resisted giving Schleifstein the green light for his investigation, James O’Byrne, now the newspaper’s director of state news and sports, says he and his colleagues’ reluctance made sense in hindsight. “It was a failure of imagination,” says O’Byrne. “People could not bring themselves to imagine an American city in the 21st century underwater. Then, lo and behold, an American city was underwater in the 21st century. Since Katrina, it hasn’t been very difficult to convince people that we need to look at the big infrastructure and risk questions. It’s the ultimate ‘I told you so.’ ”