Walter Lippmann’s long and extraordinary career embodied what magazine magnate Henry Luce described as the “American Century.” Lippmann chronicled it, tried to understand it, and ultimately shaped American politics, diplomacy, and journalism.

He began his intellectual life as a socialist, but he spent much of his career among the world’s most powerful. Lippmann was drawn to them, and such was the impact and reach of his journalism that, even if they did not want to hear from him, they could rarely turn him away. “Men like that have always fascinated me,” he said in a 1950 interview, speaking of Charles de Gaulle. “It’s as if the country is inside of them, and not they as someone operating within the country.”

One could say the same thing about Lippmann. He “may have been the most influential American of the twentieth century never to have held elected office,” writes Christopher Daly, in his book “Covering America: A Narrative History of a Nation’s Journalism.”

Daly, a professor of journalism at Boston University, says Lippmann’s impact was global and his annual international tours cast him in the role of “something like a secretary of state without portfolio.” Soviet leader Nikita Khrushchev once asked Lippmann to delay a visit to Russia because he was dealing with a crisis. When Lippmann said no, Khrushchev rearranged his plans to accommodate him.

Lippmann was unique, according to Daly, in the degree to which politicians consulted and listened to him. He built credibility, among readers and politicians, because of “the sheer amount of knowledge and hard work and dedication. These are sort of old-fashioned virtues, but that was Lippmann, and it’s hard to separate them from his success. He did his homework. He knew what he was talking about.” In its front-page obituary of Lippmann, who died in 1974, The New York Times described him as “the dean of American political journalism in the 20th century … What gave him readability and immense authority was his ability to take a tangled headline issue, analyze it coolly and relate it convincingly to the underlying problems of which it was a part. He always wrote from a background of solid information, and in this sense he was also a public schoolmaster who obliged his readers to think of the transient in terms of the everlasting.”

Lippmann cemented a reputation as a public philosopher—a métier that fits with his journalism, which was more about commentary than reportage

David Greenberg, a professor of history and of journalism and media studies at Rutgers University-New Brunswick, says Lippmann earned respect and influence because few perceived him as a partisan cheerleader: “He obviously inhabited the world of Washington. He consorted with these people, he talked to them, he was interested in having influence on them. But he was not predictably in one camp or another. And I think that’s why he was so influential and so widely read as a columnist for many years, because he wasn’t knee-jerk, he wasn’t a hack. He really followed his own life. He was a realist in foreign policy, and that led him at various times to support or oppose various presidents.”

To mark the Nieman Foundation’s 80th anniversary, Nieman Reports is re-examining Lippmann’s legacy and impact. It’s been more than 40 years since he died, but journalists are still grappling with many of the issues that defined Lippmann’s life and career: the value of reporting versus commentary; the question of who warrants our attention as journalists—the wealthy and influential or the marginalized and ignored; a journalist’s relationship with power—should journalists be outsiders or insiders, and what happens when they shift from one to the other? For Lippmann, the latter question is intimately tied to his Jewish identity.

Lippmann began as a cub reporter at the Boston Common in 1910, and soon after took a job as a researcher for muckraking pioneer Lincoln Steffens, investigating financial corruption. He joined The New Republic as a founding editor in 1913 and was writing a regular column for Vanity Fair by 1920.

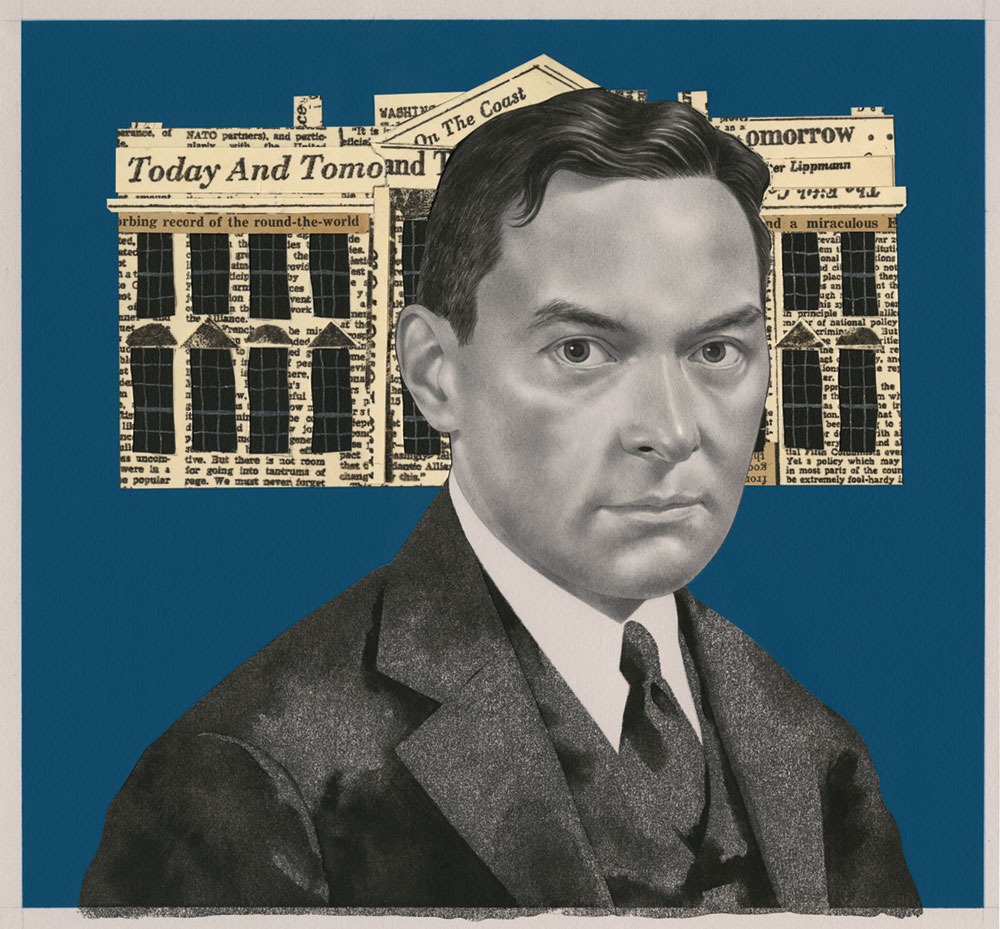

He started working for the New York World in 1922. When it closed, almost a decade later, Lippmann began his syndicated “Today and Tomorrow” column, which he would write for 35 years, usually for the New York Herald Tribune. He would produce more than 4,000 of these columns. They were widely syndicated and brought him his greatest fame. Lippmann’s accolades included two Pulitzer prizes and three Overseas Press Club awards.

Along the way, Lippmann wrote more than 20 books, cementing a reputation as a public philosopher—a métier that fits with his journalism, which was more about commentary than reportage. The philosophy that underpinned much of that commentary was liberalism, albeit a liberalism that was at times colored by elitism.

Lippmann’s connection to the Nieman Foundation for Journalism at Harvard came as a result of an unexpected bequest to Harvard from Agnes Wahl Nieman, widow of Milwaukee Journal editor Lucius Nieman. A wealthy, well-traveled, and well-educated woman from a prominent German-American family in Chicago, Nieman altered her will only four days before her death in 1936 to leave the largest portion of her estate to Harvard. Her will stipulated that the money be used “to promote and elevate the standards of journalism in the United States and educate persons deemed specially qualified for journalism.” Harvard President James B. Conant wondered, “How did one go about promoting and elevating the standards of journalism?”

It was Lippmann, a Harvard alum who sat on the university’s Board of Overseers, who steered Conant toward an answer. The money would not be used for a journalism school or an archive of newspapers on microfilm, but to provide working journalists with an opportunity to study at Harvard. Lippmann then helped secure support from Harvard’s governing board.

These ties persisted. Lippmann made a point of coming to Cambridge and speaking to each new batch of fellows during the fellowship’s early years. After Lippmann died, money from his estate went toward renovating the house where the Nieman Foundation is now based and that bears his name.

As a student at Harvard, Lippmann relished his work at the socialist Cambridge Social Union because, he said, it allowed him to reach “some small portion of the ‘masses’ so that in the position not of a teacher but of a friend, I may lay open real happiness to them.”

If journalism is history in a hurry, Lippmann’s was usually history from the top down

Four years after graduating, his political outlook shifted. “[T]he winter of 1914 is an important change for me. Perhaps I have grown conservative,” Lippmann wrote in his diary while crossing the Atlantic that July. “At any rate I find less and less sympathy with the revolutionists … and an increasing interest in administrative problems and constructive solutions.”

This change was reflected in the bulk of Lippmann’s journalism. If journalism is history in a hurry, Lippmann’s was usually history from the top down. He traversed an archipelago of wealth and influence, dining with members of the ruling classes who inhabited these islands but not with those in the seas between.

This colored the work Lippmann produced. His commentary about the suffering of ordinary Americans during the Great Depression was bloodless; people should be thrifty and control their appetites, he said. When he wrote about Nicola Sacco and Bartolomeo Vanzetti, two Italian immigrant anarchists executed for murdering two men despite another man’s confession that he committed the crime, Lippmann focused on those who decided their fate, not on Sacco and Vanzetti or the milieu from which they came. For a man who knew Europe so well, he was notably unsympathetic to its huddled masses yearning to escape a continent that, in the 1930s, seemed to be barreling toward violence and ever more virulent hate. Without specifically mentioning Jews, he suggested Europe’s “surplus” population should colonize Africa.

Related Reading

“The Present Crisis of Western Democracy is a Crisis of Journalism”

By Eduardo Suárez

“Harvard Helped Form Lippmann’s Mind”

By Ronald Steel

Such was the gilded myopia for which Tom Wolfe would later savage Lippmann. “For 35 years Lippmann seemed to do nothing more than ingest the Times every morning, turn it over in his ponderous cud for a few days, and then methodically egest it in the form of a drop of mush on the foreheads of thousands of readers of other newspapers in the days thereafter,” he wrote in a 1972 New York magazine article about the New Journalism. “The only form of reporting that I remember Lippmann going for was the occasional red-carpet visit to a head of state, during which he had the opportunity of sitting on braided chairs in wainscoted offices and swallowing the exalted one’s official lies in person instead of reading them in the Times.”

In an obituary, Lippmann’s biographer Ronald Steel wrote that Lippmann’s aversion to actual reporting was so severe that he “shied away from a scoop, even when handed to him on a platter, as though it were distasteful and slightly odoriferous.”

This may have been because Lippmann never saw himself as a reporter, but as a commentator or a political philosopher, says Nicholas Lemann, dean emeritus and the Joseph Pulitzer II and Edith Pulitzer Moore Professor of Journalism at Columbia’s School of Journalism: “I think he thought of his column as a way to be engaged and try to influence public affairs. I don’t think there was ever a moment in his life that I was aware of when he thought, ‘I hold myself separate from public officials’ or ‘I would never advise a president.’ He really functioned throughout his life as part of that very elite little corner of the political system.”

Lippmann’s ascent into that elite little corner was rapid. President Woodrow Wilson invited Lippmann to a gala dinner reception in 1916, and Lippmann would come to know every president who succeeded him up to Richard Nixon, who resigned months before Lippmann’s death more than 50 years later.

The close relationships Lippmann enjoyed with politicians can strike a modern journalist as too cozy. He relished being part of the establishment and, for much of his career, seemed reluctant to write in a manner that would threaten that membership. Lippmann also didn’t refrain from helping politicians, including by drafting papers and speeches for them, even while working as a journalist. This work included helping to edit John F. Kennedy’s inauguration address—a speech he then praised in a column.

But Lippmann worked at a time when the wall between politicians and journalists was far more porous than it is today. High-level political journalists such as Lippmann simply didn’t see themselves as outsiders in Washington, says Maurine Beasley, professor emerita of journalism at the University of Maryland, College Park. They “were part of the political establishment, and whether they should have been or not, ethically, is a question you can debate. But I think they were.”

And Lippmann was hardly alone. “He might have been at the pinnacle as one of the leading journalists. As one of the most brilliant minds, he might have been called on the most, but there are lots of others,” says Greenberg.

Lippmann eventually came to rethink the relationship between journalists and those in power. In 1964, he told a television interviewer: “There are certain rules of hygiene in the relationship between a newspaper correspondent and high officials—people in authority—which are very important and which one has to observe … There always has to be a certain distance between high public officials and newspapermen. I wouldn’t say a wall or a fence, but an air space, that’s very necessary.”

Lippmann was never obsequious, nor did he shrink from taking on presidents and the Washington establishment. He criticized Franklin Delano Roosevelt’s New Deal. He fiercely opposed Harry Truman’s strategy of containing the Soviet Union following World War II. His opposition to the Truman administration’s belligerence on Korea was even sharper. But the “air space” he said should exist between a politician and a journalist was, in his case, generally pretty small.

“Before the second half of the war in Vietnam there was kind of a bedrock assumption that the United States had an establishment, needed an establishment, and that the establishment should be made up of the best people—not in the British sense of the best born, but the most capable and the most dedicated,” says Daly. “I think [Lippmann] thought we’re all in this together, and other serious people like him who cared about the country had a common cause.”

“We operate off a set of rules that we think are normal and expected for journalists and that we think are pretty well established,” says Lemann. “Those rules basically didn’t exist until Walter Lippmann was maybe 60 years old, so we’re sort of retrofitting his life with a set of rules that he wasn’t even really aware of.”

Lippmann worked at a time when the wall between politicians and journalists was far more porous than it is today

And it may be that prevailing mores haven’t changed that much, after all. Some journalists still seek affirmation from their interview subjects and prize access over independence. Even policy consultations between journalists and politicians persist. They’re just framed differently, says Greenberg. President Barack Obama often invited journalists into the White House for off-the-record discussions, he says.

And if journalists today would not help politicians draft speeches or consciously act as an administration’s unofficial messenger, other forms of cooperation persist. It was only in 2012 that The New York Times announced it would sharply curtail the practice of “quote approval”—submitting quotes to a source before publication.

Lippmann’s willingness to cooperate with the powerful people he wrote about was also a product of his time. He cut his teeth under muckraker Lincoln Steffens. But even the muckrakers, in their turn-of-the-century heyday, were not true outsiders. They had a progressive political agenda and sought allies among politicians they thought could advance it.

Ray Stannard Baker, reporter for McClure’s magazine and among the most prominent in muckraker ranks, was tight with Theodore Roosevelt. Baker sent Roosevelt articles in advance of publication, and Roosevelt gave Baker access to restricted government files. David Woolner, a professor of history at Marist College and a senior fellow at the Roosevelt Institute, says the muckrakers’ access to Theodore Roosevelt didn’t blunt their criticism. But when there was inevitable discord, Baker tried to smooth it over.

Lippmann would also become smitten with Roosevelt. He leapt at a chance to write Roosevelt a position paper on labor. Roosevelt, who was contemplating another attempt to return to the White House in 1916, gripped the 24-year-old Lippmann’s hand and said the two were linked in a common cause, Steel writes in “Walter Lippmann and the American Century.” They would fall out, but Lippmann’s fondness never cooled.

Woolner says Roosevelt inspired excitement among progressive-minded people who believed government should have a role in giving average people economic justice. “Journalists got caught up in this idea and wanted to move it forward,” he says. “And to the extent that they wanted to be a part of it, they may have been willing to do things, cooperate with these political figures, in ways that may seem in today’s world to be crossing that line. But in the political context of the day it made sense.”

When America entered the war in 1917, Lippmann was recruited as an assistant to Secretary of War Newton D. Baker. America did not handle wartime dissent well. Publications were suppressed, editors indicted and harassed. Hundreds who questioned the war were jailed. And in a foreshadowing of congressional cafeterias selling “freedom fries” instead of “French fries” to protest France’s opposition to the proposed invasion of Iraq in 2003, sauerkraut was renamed “liberty cabbage.” Lippmann protested, with arguments built on wartime tactical considerations rather than principles.

“So far as I’m concerned, I have no doctrinaire belief in free speech. In the interest of war it is necessary to sacrifice some of it,” he told Wilson advisor Edward “Colonel” House. “But the point is that the method now being pursued is breaking down the liberal support of the war and is tending to divide the country’s articulate opinion into fanatical jingoism and fanatical pacifism.”

Later in the war, Lippmann was commissioned as a captain in military intelligence, where he worked on propaganda, and then joined the American delegation negotiating peace in Paris following the armistice. Lippmann believed in the work he did on behalf of the war effort but wanted to return to journalism. He did so in 1919.

The sense that journalists and politicians share a common goal during times of national crisis persisted into World War II, says Larry Sabato, director of the University of Virginia’s Center for Politics. Even during the Cold War, journalists tended to support their government because of the perceived stakes in America’s ongoing confrontation with the Soviet Union, he says.

With John F. Kennedy’s administration came a sense of glamour that seduced many reporters covering him. “Kennedy entranced the press, and reporters gave him even more breaks than they gave his predecessors,” says Sabato. “They were well aware of some of the comings and goings of young beautiful women and actresses and so on. They were also taken into Kennedy’s inner circle in a sense … and given inside information. The administration did not suggest to them or require that these things be off the record. They simply knew they weren’t supposed to report it. Occasionally they’d check with the press secretary and ask.”

Sabato says reporters became more confrontational during the Lyndon B. Johnson presidency, and especially so when Richard Nixon was president. After the Watergate scandal, he says, it was “open season.”

The mostly male Washington press corps and those they covered operated in kind of unofficial fraternity. They drank together, often heavily, and could be fairly confident that knowledge of certain transgressions would be kept between them. This was a time in which the public at large was willing to afford politicians more privacy than it is today. Journalists reflected this. But those writing about politicians also feared losing access.

The roots of Walter Lippmann’s insecurity about losing his insider status may have begun with his upbringing as an American Jew in late nineteenth- and early twentieth-century New York. It seems that insecurity left him hesitant or slow to write about those who hadn’t reached a similar level of status and social acceptance, and on occasion to commit errors of judgment when he did so.

Lippmann was never obsequious, nor did he shrink from taking on presidents and the Washington establishment

In his biography of Lippmann, Steel describes young Walter, who was born in 1889, growing up among wealthy and thoroughly assimilated German Jews who shut themselves off from more recently arrived migrants fleeing the pogroms of Eastern Europe. Those Jews, the Lippmann crowd believed, were too loud and obviously foreign. The rabbi of the Emanu-El temple where the Lippmanns prayed praised his congregation because its members were “no longer Oriental,” meaning Polish or Russian.

Lippmann carried a desire to shed any foreign vestige with him to Harvard, where he learned this wasn’t as easy as he had hoped. Final clubs, unofficial social clubs that functioned as a sort of escalator into America’s ruling class, didn’t want Jews as members. He wasn’t invited to join The Harvard Crimson student newspaper either. His background and faith limited his options. Lippmann rebelled, briefly. But for most of his life he tried to hold on to his place within establishment bastions, rather than forcing their gates.

This was especially true concerning Judaism. In the 1920s, several universities began imposing limits on the number of Jews they would admit. Harvard, after what Steel describes as a bitter faculty debate, chose not to. But Harvard University President A. Lawrence Lowell remained unhappy about the “excessive” number of Jews at Harvard and appointed a committee to reconsider.

One committee member asked Lippmann for his thoughts. In a draft letter, which Steel could not determine was delivered, Lippmann said he was prepared to accept the judgment of Harvard authorities who believed more than 15 percent Jews in the student body would lead to segregation and confrontation between Jews and gentiles. His sympathies lay with “the non-Jew,” he added: “His personal manners and physical habits are, I believe, distinctly superior to the prevailing manners and habits of the Jews.” Lippmann thought Jews should assimilate.

He supported “a more even dispersion of the Jews, and of any other minority that brings with it some striking cultural peculiarity.” As a way around quotas, he suggested Harvard select more students from parts of the country where fewer Jews lived. He was against any “test of admission based on race, creed, color, class or section,” he wrote in the letter.

Harvard imposed an informal quota on Jews all the same. Lippmann publicly condemned it. “Harvard, with the prejudices of a summer hotel; Harvard, with the standards of a country club, is not the Harvard of her greatest sons,” he wrote in an editorial.

Jews at this time in America had to walk a difficult line. Some, such as Lippmann, had achieved social prominence. But there was enough discrimination in society, and memories of far worse bigotry, that the position of even those who had reached such high status must have felt precarious.

In a February 1938 letter to Helen Byrne, who would soon become his second wife, Lippmann described his friend Carl Binger as having a somewhat “oppressed” spirit because “he has that rather common Jewish feeling of not belonging to the world he belongs to.” Lippmann understood these emotions but did not share them, he added: “I have never in my life been able to discover in myself any feeling of being disqualified for anything I cared about.”

But Lippmann was disqualified from things he wanted at Harvard. In the same letter, Lippmann listed a number of injustices faced by Jews, from exclusion from some summer hotels to job discrimination, but concluded that one should learn not to care about such things. It’s hard not to see Lippmann’s desire to subsume his Jewish identity reflected in his journalism. He rarely wrote about Jewish issues, and when he did the results could be disastrous.

The roots of Lippmann’s insecurity about losing his insider status may have begun with his upbringing as an American Jew

In a 1933 column, in which he also described a speech by Adolf Hitler as “statesmanlike” and “the authentic voice of a genuinely civilized people,” he urged readers not to condemn all German people because of the uncivilized things that are said and done in Germany.

He wrote, “Who that has studied history and cares for the truth would judge the French people by what went on during the Terror? Or the British people by what happened in Ireland? Or the American people by the hideous record of lynchings? Or the Catholic Church by the Spanish Inquisition? Or Protestantism by the Ku-Klux-Klan? Or the Jews by their parvenus? Who then shall judge finally the Germans by the frightfulness of war times and of the present revolution? If a people is to be judged solely by its crimes and its sins, all the people of this planet are utterly damned.”

Shortly after America entered World War II, Lippmann wrote a column about the “enemy alien problem … or much more accurately the Fifth Column problem” on the Pacific Coast. America, he said after talking to military officials, was in imminent danger of a combined attack from within and without.

President Roosevelt authorized military authorities to remove anyone it chose from military zones on the West Coast. Japanese Americans were given 48 hours to pack up or sell a lifetime of goods and were shipped to internment camps. More than 100,000 people, mostly American citizens, were detained in barracks behind barbed wire fences as if they were criminals or prisoners of war.

Lippmann’s defense of repressive measures reflected popular hysteria, and perhaps demonstrates how difficult it can be for journalists to clearly assess events as they unfold, without the benefit of time and distance. “Very often the conventional wisdom turns out to be wrong, or it’s overtaken by events, or it’s discredited in one way or another. So, if you epitomize the conventional wisdom, that’s going to happen to you,” says Daly, speaking of Lippmann.

Steel writes that Lippmann had no personal prejudice against African Americans. But he largely overlooked their struggles until they became an unavoidable part of the national conversation. In 1919, Lippmann advocated “race parallelism,” roughly meaning separate but equal, which qualified as a progressive opinion at the time. He wrote little about segregation in the ensuing decades.

Barry D. Riccio, in his book “Walter Lippmann–Odyssey of a Liberal,” describes Lippmann’s relationship to civil rights and the civil rights movement as “especially illustrative of his rather conservative brand of liberalism.” Discussions about the issue were bound up with considerations of precedent, constitutionalism, and order. “Rarely did it seem to be a matter of race or morals.” Riccio says that when Lippmann did address civil rights in the mid-1950s, he did so through a Cold War lens. Jim Crow made America look bad internationally, diminishing its global appeal.

Lippmann’s framing of civil rights in America as, at least partly, a Cold War issue was not an uncommon position as America vied with the Soviet Union for influence in Africa and other parts of the developing world. His broader caution was also not unique. Yet Lippmann’s views could change, and on civil rights, they did.

Lippmann’s defense of repressive measures reflected popular hysteria

He supported President Dwight Eisenhower’s dispatch of federal troops to Little Rock, Arkansas in 1957 to ensure school desegregation. By 1963, following the Freedom Rides, the use by police of attack dogs on peaceful demonstrators in Birmingham, Alabama, and the March on Washington organized by the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr., Lippmann realized “equal rights could not be achieved by persuasion alone,” writes Steel. Lippmann concluded desegregation must become a national movement led and directed by the federal government.

Lippmann was not indifferent to the discrimination women faced. At Harvard, he wrote of the suffragists: “They are unladylike, just as the Boston Tea Party was ungentlemanly, and our Civil War bad form. But unfortunately in this world great issues are not won by good manners.”

Lippmann’s “rather conservative brand of liberalism,” as Riccio describes it, meant he was rarely at the forefront of journalism related to the rights of the disenfranchised and overlooked. Journalists today can miss stories and misjudge the strength of movements for similar reasons.

In the twilight of his career, Lippmann adopted an iconoclasm he had until then largely avoided. The trigger was the war in Vietnam.

President Johnson seemed to want Lippmann’s help. Less than two weeks into his presidency, he asked to come over to Lippmann’s house for a chat, recounts Steel. The two were on good terms for a time, with Lippmann visiting Johnson’s Texas ranch a couple of months later. They blasted down ranch roads in a Lincoln Continental, stopping to drink whiskey and soda while Johnson leaned on the car horn to warn cattle wandering nearby. Whatever genuine

affection Johnson’s attention and flattery might have engendered, it didn’t blind Lippmann to the flaws in Johnson’s decision to escalate America’s military involvement in Vietnam.

The escalation came amidst frequent consultations between Lippmann, Johnson, and members of Johnson’s administration—which, for Lippmann, might have added to his later sense of betrayal and disappointment. Because the White House did not want to alienate Lippmann, Steel writes, Johnson and his national security advisor, McGeorge Bundy, kept telling him they would be willing to negotiate a settlement in Vietnam once the military situation there improved. Their real objective was winning the war.

Lippmann grew skeptical of what the White House was telling him. He also recognized that military success would require more blood and treasure than America was willing to expend, and that American interests in Vietnam were too minuscule to justify the sacrifice. Concluding privately in 1965 that he had been “pulling my punches,” Lippmann endeavored to more forcefully expose the folly of Johnson’s Vietnam strategy. “There are some wars which must be averted and avoided because they are ruinous,” he wrote the following year. Lippmann had avoided personal attacks on Johnson but now accused him of “messianic megalomania.”

Lippmann picked this fight even as most American media, including his home paper, The Washington Post, backed the war. He suffered derision and hostility as a result. Johnson, who had once draped an arm around Lippmann and proclaimed, “This man here is the greatest journalist in the world, and he’s a friend of mine!” now told guests Lippmann was senile and mocked him in public.

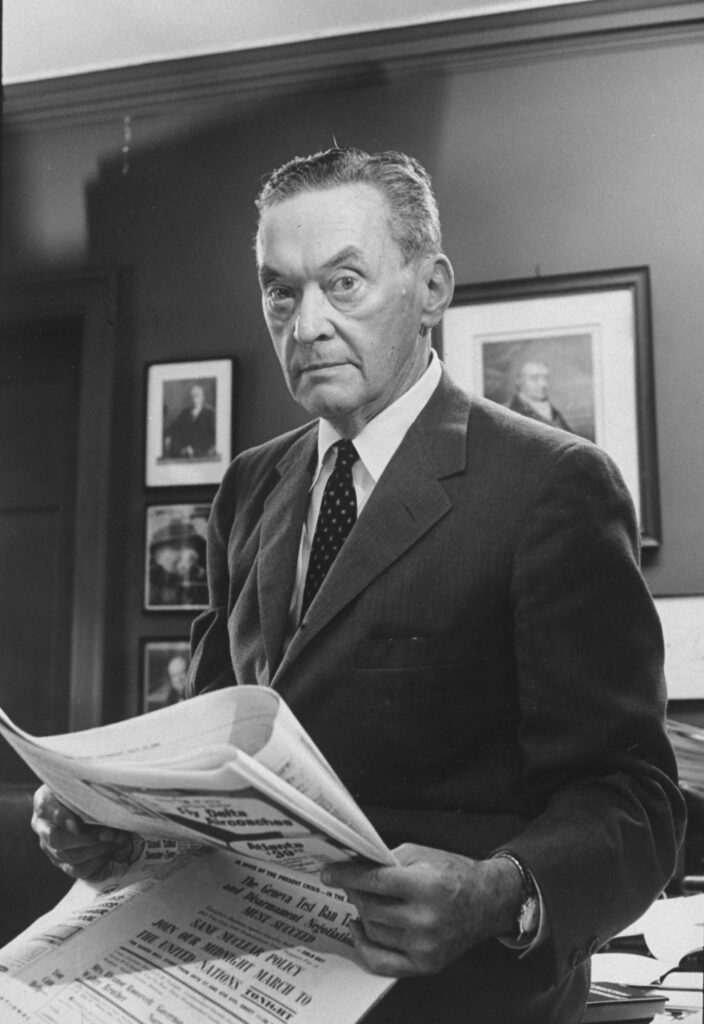

But Lippmann made no attempt to write his way back into favor. When Lippmann decided to leave Washington for New York and stop writing his regular “Today and Tomorrow” column in 1967, he told colleagues at a farewell dinner that he was not leaving “because I no longer stand very near the throne of the prince nor very well at his court” but because “time passes on.” “Change and a new start,” he added, “is good for the aging.”

Looking back on Walter Lippmann’s life, Ronald Steel concluded there could never be another to match him: “The mold that Lippmann filled so impressively no longer exists.”

This is true on many levels. His productivity, range, and impact have not been equaled since. Few political philosophers ever reach the audiences Lippmann did, and even fewer have the capacity to simultaneously write multiple columns a week for decades on end.

He also lived during a different time in American journalism. Writing in 1998, Steel recognized its landscape had already irrevocably changed: “The sources of news and opinion are too atomized and varied. No single person can encompass them all.” The scope of what is covered today has also changed. People and communities whose stories seldom appeared in newspapers 80 years ago are no longer as ignored.

What’s considered an acceptable relationship between a journalist and a politician has shifted, too. Here, Greenberg shares Lemann’s caution against judging historical figures by today’s ethical standards. “It’s very easy to cast a moralistic eye backward on someone like Lippmann. But I think the reality is high-level journalism and high-level Washington politics are intertwined, and it’s human nature to be seduced by power, so I’m not particularly judgmental of Lippmann,” he says.

Lippmann, says Greenberg, believed the personal influence he could have on politicians was part of his role as a journalist and thinker. “The ethics of the time didn’t really proscribe that,” he says.

Looking back on Walter Lippmann’s life, Ronald Steel concluded there could never be another to match him

Lippmann was at times horrendously wrong—about Hitler in 1933, about the herding of Japanese Americans into internment camps a decade later. But his warnings about the dangers of America overextending itself abroad, his insistence that the country should limit its interventions to places where vital interests are at stake (not Vietnam), would resonate today among American policy makers who feel they’ve had to learn those lessons all over again.

And if Lippmann was often elitist, he was in the end a democrat who believed that if a country is to be governed with the consent of its people, journalists must provide citizens with the information they need to decide how they want to be governed. “This is our job,” he said in a speech to a National Press Club gathering in honor of his 70th birthday in 1959. “It is no mean calling. We have a right to be proud of it and to be glad it is our work.”

Lippmann’s career was characterized by re-evaluation and continuous learning. It is tempting to see a reflection of this in Lippmann’s support for the Nieman Foundation and the fellowships it provided so that journalists might study at Harvard and enhance their skills. Lippmann wrote for as long as had something to say and his health would permit, writing his final article in 1971 at the age of 81. Facing death a few years later, he was calm and impassive. “At no time did he ever speak of prayer or God or an afterlife,” his lawyer, Louis Auchincloss, recalled. “Whatever was or would be, he accepted.”