Even as our newsroom numbers have dwindled, The Hartford Courant has held on to a tradition of strong investigative work. So at a brainstorming session in early 2005, one of our bosses urged our desk to think big, to cast aside concerns about geography and cost, and reach for the most meaningful stories we could write.

"You have to understand," she said directly. "The editor has given us a blank check to save lives and right wrongs, anywhere in the world."

That bold edict may sound heretical at a time when cost-cutting and hyperlocal initiatives dominate the agenda at American newspapers. But watchdog journalism is part of the foundation of the press, and the investigative desk here holds fast to the notion that readers can care deeply about events going on well beyond their zip codes.

In the winter of 2005, we were pretty sure they cared deeply about the Iraq War. And as the conflict entered its third year, we began thinking about two basic questions: With media reports showing recruiting shortfalls and pressure to maintain troop strength, was the U.S. military lowering the bar and sending soldiers to war with serious mental illnesses? And were troops who developed mental problems in the war zone receiving the treatment they needed? Those questions led us to make some initial calls to veterans' advocates and other sources, and they encouraged us to look further into the gaps in mental health care.

Since Connecticut's only active military installation is a submarine base and relatively few of our residents have fought in Iraq or Afghanistan, another question we raised was whether this would be a worthy story for The Hartford Courant to pursue.

Our answer: absolutely.

Meshing Personal With Policy

The hyperlocal crowd makes a persuasive market-economics argument that newspapers should direct resources to the stories that no one else can do — community and statewide news beyond the reach of the national outlets. But there must be room for pursuing significant stories that the national players simply aren't doing. In our early research exploring this topic, we found a lot of stories focused on mental health issues for veterans. What we had a much harder time finding was any in-depth print reporting on the mental fitness of those still in the war zone or heading there. So that's where we set our sights.

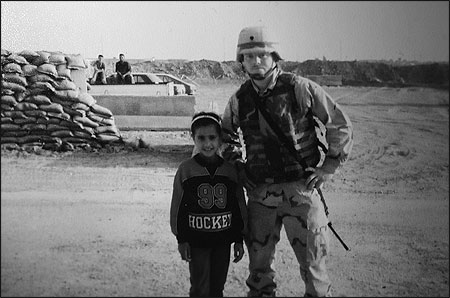

The result, more than a year later, was a four-day series revealing that the military was sending, keeping and recycling mentally troubled troops into combat, often in violation of its policies. We discovered that despite a congressional mandate to assess the mental health of all deploying troops, the military's own data showed that not even one in 300 service members was seen by a mental health professional at deployment — far fewer than the military believes have serious mental health issues. Our reporting also showed that the military was increasingly relying on psychotropic medications to keep mentally troubled service members in combat, often with minimal monitoring and counseling. And our series revealed that a growing number of troops suffering posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) were being sent back to the battlefield for second, third and fourth tours of duty, at an increased risk to their long-term mental health.

We attacked the story from two sides. In seeking military information, we battled with the Department of Defense to obtain their data and reports that revealed systemic flaws in the military mental health system. We also reached out to the families of service members who had committed suicide in Iraq and with their help were able to bring readers face-to-face with the human cost of these flaws. The following circumstances were among those we discovered and wrote about:

- We found one soldier kept in Iraq by commanders who overruled a military psychologist's finding that he should be sent home.

- Another soldier was referred for a psychiatric evaluation after e-mailing a chilling suicide note to his mother but was ultimately punished and accused by the psychologist of faking his symptoms.

- An Army private from California told fellow soldiers he had dreams of raping and killing Iraqi children, and he repeatedly put his weapon in his mouth and pulled part way on the trigger.

- A soldier from Pennsylvania had the nickname "Crazy Eddie" and had spent his youth on anti-psychotic and anti-epileptic drugs.

Each of these troubled soldiers committed suicide in Iraq. But their stories had never been told.

Our two-pronged approach was critical to the project's success. A statistics-laden "system" story would have bored readers. Yet a series of stories constructed exclusively on anecdotes would have left them wondering if these soldiers' experiences were the norm or extreme exceptions. By combining the two, we produced journalism that resonated with readers and prompted quick congressional and military action. Within months of the series' publication, the military, under orders from Congress, adopted sweeping new rules to protect mentally ill troops before and during deployment.

The soldiers whose lives — and deaths — we wrote about came from Oklahoma, Texas, Virginia, Maryland and elsewhere. One was from Connecticut. Despite this geographic distance, we had faith that our readers would be interested in the revelations about what led these soldiers to take their own lives. Working on this series, and hearing reaction from readers near and far, reminded us of an abiding belief about journalism. Even as our subscribers expect strong local coverage, when they are given well-reported and important stories from anywhere the result is enthusiastically received and the paper's journalistic ambition applauded.

After the series, "Mentally Unfit, Forced to Fight," was published in May 2006, more than 100 people left notes on its online message board. From a small town in our circulation area — a town that hasn't buried a single soldier in the war — came the words, "I'm proud of my hometown paper for printing this story." Not one person questioned why The Hartford Courant decided to devote its space and reporters' time to this story.

Digging for Accurate Information

Reporting these stories offered each of us valuable lessons in the nuts and bolts of investigative reporting. Neither of us had covered the military, so when we began our work on this story, we arranged some early interviews with experts from inside and outside the Armed Forces. (By the time we finished our reporting, we'd interviewed more than 100 mental health experts, military personnel, family members, and friends.) From what we learned in these initial interviews, we identified key questions and sketched out directions to head in to find the answers. While doing our reporting, we maintained a relentless optimism that answers were out there and, in time, we would find them and that when answers can be found in government records, which are after all public documents, our newspaper never stops at "no."

When we sought access to a military database with information on predeployment mental health screening for nearly one million troops, we were turned down. When we requested dozens of investigative reports into deaths we suspected were suicides, we were told it would be eight months before our request was even considered. But we persisted, we cajoled, we flattered, we threatened. We knew the Freedom of Information Act (FOIA) laws better than they did. And, ultimately, we got what we needed.

Early on, we also decided to analyze suicides in the war zone, because that was the measure the Pentagon had used in declaring a mental health problem after a suicide spike in 2003 and the same measure it used in praising new mental health efforts after the suicide rate dropped in 2004. But the military does not identify suicides and instead includes them in a large group of "nonhostile" deaths — a vague reference hometown newspapers typically repeat in reporting on fallen soldiers.

Nearly one in five U.S. military deaths in Iraq have been classified as "nonhostile." We were determined to figure out which were suicides. So, working with a database of all nonhostile deaths, we eliminated those that did not appear to be suicides — such as deaths in fires and aircraft crashes. We then searched for clues about the other deaths by finding obituaries, news stories, online memorial sites, and even looking in MySpace.

Once the number was reduced, we faced the unpleasant task of making cold calls to grieving relatives to try to confirm the cause of death and learn the soldiers' stories. Sometimes we called directly, but often we took a more circuitous route by making our first contact with more-distant relatives or friends or clergy members. For one soldier, we started with a high school librarian and worked our way to the family from there.

It would have been easy to convince ourselves that families were never going to talk to us about suicide and that we should respect their privacy and not bring up what for many was a painful secret. Instead, we made the calls and, to our surprise, family after family after family eventually opened up to us, not only willing, but often grateful to be able to share with us what happened to their children and their concerns about how their loved ones were treated by the military.

We learned from this experience never to precensor ourselves nor to make assumptions about who will talk with us. The first family we contacted turned out to be holding one of our most compelling stories: Their son had been sent back for a second tour with symptoms of PTSD. His suicidal indicators were repeatedly overlooked by his command — until he put his weapon against his head and pulled the trigger.

We kept digging and ultimately identified every war-zone suicide in 2005, discovering along the way that the military's suicide rate had reached record levels, a fact that the defense department would finally acknowledge seven months later.

We were committed to learning every story we could and, with the paper's support, we had time to win the trust of shattered families. Some families spoke with us for months but never became comfortable with the idea of being quoted in the paper. Most did ultimately agree to break what had been their silence about their child's death. By the time we published, we had close to a dozen heartbreaking tales about soldiers who remained in the war zone and committed suicide, despite clear signs that they were psychiatrically fragile.

RELATED WEB LINK

For online links for the original series, videos of interviews with soldiers' parents, and subsequent coverage of these issues, visit www.courant.com/unfit.The portrayals of these soldiers' lives and deaths were ones that readers — in Hartford, in Washington, and beyond, found hard to ignore. And we've stayed with this story. Since May 2006, our newspaper has continued to report on a range of issues related to the mental health of U.S. troops, including coverage of legislative efforts in Congress to expand mental health screening for combat troops and establish clear mental-fitness standards for deployment to war zones.

The Hartford Courant has produced terrific local investigative stories, including aggressive work that toppled a corrupt governor and, more recently, a series that exposed a mismanaged nursing-home chain and prompted legislative reforms for the entire industry. But our experience with this series reminded us that even midsize papers — even intensely cost-conscious midsized papers — do not need to abandon the goal of pursuing investigations into wrongdoing, no matter where in the world it happens.

The enormous response to our series from local readers told us this was a project our paying subscribers felt well served by. What we heard from people throughout the country told us this was meaningful public service journalism that transcended circulation zones. As newspaper publishers search for a new business model, they should recognize that those two concepts go hand-in-hand.

Matthew Kauffman and Lisa Chedekel are reporters at The Hartford Courant. "Mentally Unfit, Forced to Fight" won the 2006 Worth Bingham Prize, the 2006 George Polk Award for Military Reporting, the 2007 Selden Ring Award for Investigative Reporting, the Dart Award for Excellence in Reporting on Victims of Violence, the Heywood Broun Award, and was a finalist for the Pulitzer Prize in Investigative Reporting.