A reporter in the Washington bureau of the Knight newspapers, Meyer arrived at Harvard to learn how to apply social science research to reporting. The result: The invention of precision journalism

Computers were a mysterious and expensive new technology when I prepared my Nieman application in 1966. But politicians were already starting to apply them to the problem of winning elections. As a Washington correspondent, I needed to understand how that worked. The selection committee liked the idea.

At Harvard, I quickly learned that the graduate seminar I wanted was too advanced for me. My M.A. in political science had been based on old-fashioned qualitative methods. So I joined a group of sophomores in Social Relations 82, a course in research methods with this disclaimer in the catalog: “There is no presumption of familiarity with statistics or computer techniques.”

The instructor was Chad Gordon, who turned out to be young, untenured and eloquent. I still have my notes from that course with his opening sentence, “There are no serious logical breaks between the social sciences and the physical sciences.” We were introduced to an innovative statistical package written by Harvard faculty for the IBM 7090, a large machine with eight tape drives and flashing lights to indicate its many input-output operations. Each student was allocated three minutes worth of that machine’s core memory.

About a third of the way into the semester, I realized that Gordon’s tools for quantifying aspects of human behavior could be applied to newsgathering. I remembered newsroom discussions about attitudes that motivated political participation and our regret that there was no way to measure them. Now, I realized, there was a way. When I coaxed the computer into producing a particularly impressive stack of tables, I carried them to a Nieman social event at Signet House and spread the continuous sheet across the floor.

“Package it and sell it,” said David Hoffman, a classmate from The New York Herald Tribune. I liked that idea, and in the second semester, I audited upper-level courses to gain confidence in both statistics and computing while hanging out with graduate students in the Department of Government.

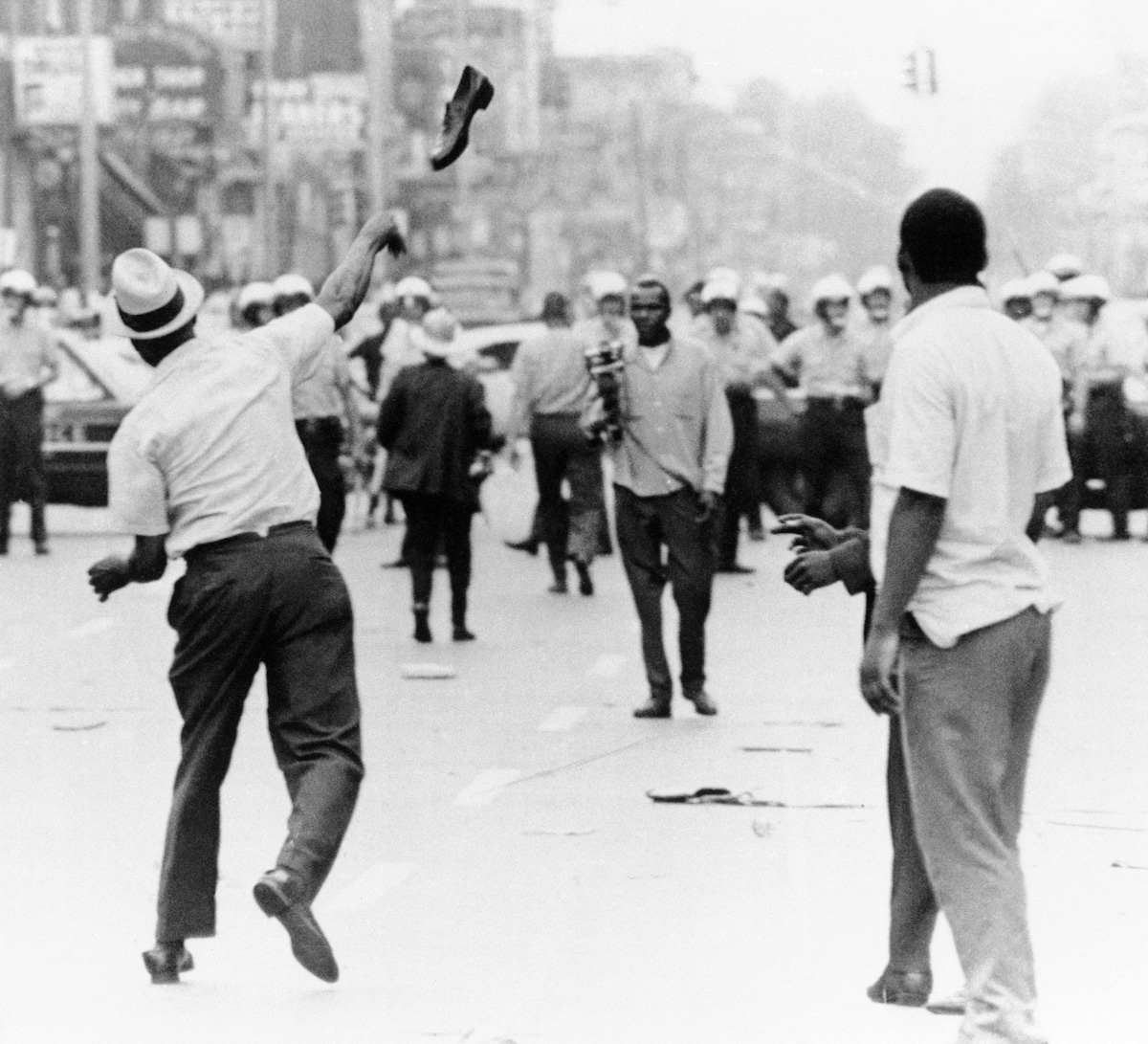

Back on the job in Washington, I was alone in the Knight bureau when the phone rang. Detroit’s race riot was in its fourth day and the Free Press needed more reporters. Since I was the one who answered the phone, I got to go. When the riot was over, I proposed a scientific survey to measure the attitudes and grievances that caused it. The report was published three weeks later. My new career had begun.