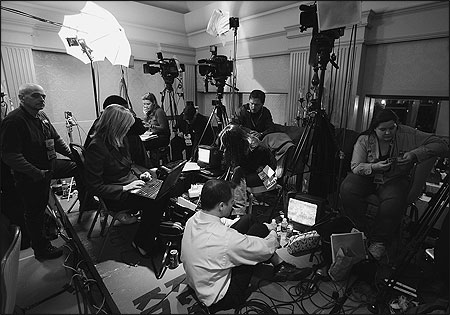

On the night of the Iowa caucuses, members of the news media wait for results at the site of Senator Clinton's rally. January 2008. Photo by Christopher Gannon/Des Moines Register.

In early January, I sat in an airport hangar in Manchester, New Hampshire, waiting for Senator Hillary Clinton to emerge the morning after her loss in Iowa. My toes were numb from the frigid cold outside where we had waited while the Secret Service swept the building. But my hands were warmed by a pair of fingerless cashmere gloves that allowed me to keep typing, no matter where we traveled.

We arrived there before 7 a.m. and, after she spoke, a videographer and I left the building in search of a wireless signal that would allow me to send a blog post to New York. It was the beginning of another long day of living life on the Web, filing and editing post after post in a political season that has seemed endless.

Perhaps no other primary season would be as suited to the newspaper industry's transition to Web journalism as this one has been, with all its twists and turns and, early on, so many candidates. Competition in political coverage had been moving more and more online in the past few years. But for 2008, political blogs and politics Web sites exploded on the scene, creating longer and longer blogrolls, more than enough buzz, and sizzling RSS feeds to keep politics and political junkies (including journalists) up to the minute.

What We Hear Online

When we created The Caucus, the politics blog for The New York Times, in September 2006, we never imagined that it would become a rolling news wire, with a dozen or more reporters filing as many as 20 posts a day, or that it would attract thousands of readers' comments on any given day. And now, millions upon millions of page views a month.

Having been a print reporter and editor all of my career, I had long been familiar with Web journalism and had shifted more and more of my reading to online work. But now that I've moved over to the Web itself as an online politics editor, I'm frequently awestruck by the simple power of the Web and our blog, by the ability to engage readers in an immediate way, to telegraph and communicate in real time.

Rarely does a spelling error or a factual mistake last long in a blog post; readers have become our editors online, too. And they're even more active in suggesting story ideas or pointing out new developments or asking in their comments why we haven't mentioned (within minutes) that another superdelegate came out for Senator Barack Obama or Clinton.

On any given day, I have more insight into what readers are thinking than I ever did in the past. Granted, reader comments online do not reflect a random survey of public opinion, so drawing conclusions about this readership can't be done. Caucus readers who comment online can use aliases (just one per person) and, as of yet, do not have to register their e-mail addresses. So it's difficult to verify their identities (meaning some could surely be campaign loyalists posing as average readers or sock puppets, as we call them). But they do provide a window into how issues and candidates are shaping their opinions. We see incredible spikes in views and comments when we post items on Iraq or when we're live-blogging debates or big primary nights.

When rumors start to circulate online, we see them among readers' comments long before they're confirmed or transformed into news stories. At times, the dialogues they commence online unfold in thoughtful and provocative ways. At other times, especially during the protracted Democratic primary, the two camps — Obama and Clinton supporters — descend into bitter infighting.

In the past, I rarely had the opportunity to talk to our readers. Now, on occasion, I'll dive into comments — more often than not these days to ask them to be civil toward one another in a way that makes me feel like a schoolmarm. Sometimes I exchange e-mails with a reader who is asking a question. Nearly all of my interactions have resulted in expressions of gratitude for being accessible, for actually acknowledging their comments.

None of my observations are new to liberal bloggers or online activists whose devotion to the so-called democracy of the Internet has pushed and influenced political discourse for quite some time now. Or to those advocating citizen journalism. As our readership has grown, though, so has this community. Some readers have put down roots on the site; others move in and out depending on their interest in news or their level of interactivity.

In short, these online readers can be quite demanding and expectant in our changed journalistic world. Because of the war in Iraq and a majority of Americans believing this is a "change" election, voters and readers are far more engaged in this cycle.

Feeding the Web

For so many of us who now work online, the news cycles keep on churning. We had become accustomed to cable TV and the 24/7 news environment. But this political season has altered even those cycles and retooled the way we cover politicians and their campaigns. While there remains an appetite and a commitment for thoughtful enterprise in the paper and for investigative articles on candidates' backgrounds, strategies and finances, there is now a driving demand among readers and our peers for more immediate news. The online traffic cycles — that peak in the afternoon while people are presumably working — collide at times with journalists gearing up for the late afternoon print deadlines.

And the campaigns have evolved, too, with rapid-response e-mails and alerts to new videos and sound bites and articles filling our in-boxes and our Web sites. They have new props and tools to gauge the candidates (their Facebook/MySpace numbers, for one example, and another their online fundraising). Print journalists like me have been forced rather quickly to learn multimedia approaches, through audio and video and telegram-like tools such as Twitter. Podcasts are routine.

In some ways, those two pillars of coverage — enterprise and breaking news — have always posed a conflict for journalists, competing for their time and their resources. But that conflict seems heightened in this election cycle because so much of the competition has moved online. The echo chamber has become louder; the endless TV loop of a sound bite bounces up on YouTube and reverberates quickly. It becomes difficult to set aside a controversy over, say, the Rev. Jeremiah Wright, Jr. and Senator Obama, when video excerpts of his sermons are in constant replay.

It's also become harder to squirrel away a lot of what we hope are exclusive tidbits for a longer piece — most tend to find their way onto somebody's Web site within minutes or hours. We don't often have the luxury of sitting back and weighing in two or three days later with analysis. The news gets stale faster, fueling the desire to keep refreshing the blog and home page with something new, especially in the mornings and afternoons. It's the reverse of the print cycle.

Reporters and editors have less and less time and more and more responsibilities to file, and to keep filing. While a few others and I are dedicated solely to political Web coverage here at the Times, more commonplace are multitasking journalists: candidate reporters on the bus filing posts by their BlackBerries, uploading recordings of news conferences, and taping their observations for Web audio. And somewhere in the middle of the day, filing a summary of their plans for articles for the paper and then writing on deadline in between rallies, town-hall meetings, and boarding planes.

Competing Forces: Web and Print

As the newspaper industry shrinks and convulses and staffs become smaller, I realize that I'm in a fortunate position, because the Times still maintains a vast array of resources. But even here, we've just begun to acknowledge the impositions posed by our dueling missions of Web vs. print — and the crushing workload that many journalists face by trying to serve those two purposes in the wake of competing pressures.

While most of the print articles are posted online, we have yet to agree on how (or whether) to accomplish the reverse. Many journalists balk at the idea of publishing in print the more conversational blog items or first-person-on-the-trail pieces that live naturally online. Citing print standards or adhering to a more rigid newswriting style, these gatekeepers (with completely admirable goals) contribute to the ever-expanding workload. And to some extent, that continues to undermine the notion of truly integrating newsrooms for the Web and print.

As much as the newspaper prides itself on quality journalism through enterprise and analysis, it has yet to establish a system that would value reporters (myself excluded here) who have shifted their commitment and coverage to the online world on an equal par with those whose sprawling print enterprise is so highly praised. In essence, even as the political cycle has evolved and provided a rich and encouraging environment for Web journalism, a two-tier system remains for many of its practitioners, online and off.

While that's worrisome to me, I imagine that our ever-changing industry, one filled still with promise because of the information continuum that has radically transformed the ways in which we synthesize and transmit news, will ultimately come to terms with the landscape of the Internet.

Kate Phillips, a 2003 Nieman Fellow, is the online politics editor for The New York Times. She writes and edits for The Caucus, the politics news blog.