Stuart Brotman’s book, “The First Amendment Lives On: Conversations Commemorating Hugh M. Hefner’s Legacy of Enduring Free Speech and Free Press Values,” set for publication by the University of Missouri Press in April 2022, contains eight in-depth interviews with pioneers of free speech. The excerpt below features Brotman’s conversation with Floyd Abrams, an attorney at the law firm that represented The New York Times during the Pentagon Papers case.

In the 1971 case formally known as New York Times v. United States, the Supreme Court weighed whether President Richard Nixon’s administration violated the First Amendment by attempting to block The New York Times and The Washington Post from publishing the Pentagon Papers, a report by Secretary of State Robert McNamara detailing the root causes of the war in Vietnam. Though the court sided with The Times, Nixon argued that national security required prior restraint, or government action that preemptively prohibits expression before it occurs. Forty years later, The Times faces another prior restraint case, this time as a judge has barred the paper from publishing documents from the conservative group Project Veritas.

In conversation with Brotman, Abrams discusses the behind-the-scenes decision-making involved in the case and the legal challenges The Times navigated before the court:

Floyd Abrams: I became a partner at Cahill Gordon & Reindel in October 1970. Unknown to me, The New York Times had been working for a few months on a blockbuster story about the war in Vietnam. Of course, the war there was going terribly. It was getting more and more controversial, as more young men were drafted and more of them were killed in the war.

Secretary of Defense [Robert] McNamara in the late 1960s ordered a study to be prepared about how we got into the war in Vietnam. I’ve often thought that one would have preferred if the study were made before the war. So the Pentagon Papers were created. That was called the McNamara Report — twenty-three volumes of Defense Department documents, all of them were highly classified, and some of them really secret by their nature.

At that time, there was a consolidated case in the U.S. Supreme Court about confidential sources dealing with three similar cases. I’d worked on the NBC side and in the lower courts, and the media lawyers for the other two cases had an idea. Why don’t we do one brief for all of us? The question was who would we get to write such a brief.

We scheduled a meeting to discuss the idea. My suggestion was Alex Bickel, my law professor from Yale. It was clear by then, we thought, that we really had four votes in our favor — the four really liberal guys on the Supreme Court. But we didn’t know about anyone else.

Hiring Bickel also would be strategic. He was viewed as a conservative and indeed was a conservative scholar about the Supreme Court, yet one who wrote for TheNew Republic and supported Robert F. Kennedy [in his 1968 presidential bid]. In any event, Bickel was highly respected by the justices on the right of the Court in those days. So Bickel was retained. I was the one that called him to do that. I remember the call very clearly.

Stuart Brotman: Bickel then came for the meeting with the media lawyers in New York, right?

Abrams: Yes, he came in to meet his clients. I don’t think he ever had a client. In fact, I know he’d never had a client. There were all these media lawyers in the room. It was June 14, 1971. The Pentagon Papers started to be published on a Sunday. The lunch that I hosted was on a Monday, the next day. So everybody was talking about the New York Times and its publication over two days of articles based on this secret study.

Now what I didn’t know, and what was unknown outside the New York Times, was that the government had threatened The Times if they published these articles. There were great internal debates, and this would have involved calls with Attorney General John Mitchell. A telegram was then sent by Mitchell, the night of our lunch at which Bickel and I mostly spoke about confidential sources. But we all agreed that The Times would be fine.

I’ve often said, lawyers without clients are the surest people in the world. Why would Nixon go to court? We didn’t know. Secretary of State [Henry] Kissinger was telling Nixon about secret negotiations with China, for what later became an important and valuable meeting. Kissinger was saying, “There won’t be any respect for the U.S. in China if we can’t control our own secrets.” The government wrote a telegram to the New York Times saying they were going to go to court if The Times didn’t stop publishing. But Bickel had said at our lunch, “You know, there haven’t been prior restraints on journalists publishing the news. And this is the news.” Then the telegram arrived at The Times threatening litigation if the paper did not stop further publication.

So they called Alex at midnight, one in the morning. They agreed that he needed a law firm to work with.

Brotman: Wasn’t this because the law firm representing The New York Times declined the case because of a conflict of interest?

Abrams: When The Times called their outside law firm that had represented then for 60 years, that firm (headed by former U.S. Attorney General Herbert Brownell) — which had strenuously urged The Times not to publish the Pentagon Papers — refused to represent them. So The Times found itself without counsel in the most threatening case of its existence, one that their outside counsel had told them could well lead to criminal convictions of the newspaper and its publisher. And that was when, with our luncheon fresh in mind, they called Alex Bickel at midnight and asked him to lead their defense of the case. Bickel had never argued a case in court. But he was a constitutional expert of great distinction and was held in high regard by the Supreme Court, particularly its more conservative members.

With Bickel on board, James Goodale, The Times’ general counsel who had strongly urged the newspaper to publish articles based on the Pentagon Papers, called me to ask if I and my firm, Cahill Gordon and Reindel, would work with Bickel in defending The Times. I told him that I certainly wanted to do so but would need my firm’s approval, which I obtained the next morning.

I picked up Bickel in a taxi about one in the morning from his mother’s apartment and the two of us went to my office where we spent the night first locating and reviewing the Espionage Act, which the government was claiming The Times had violated and then reviewing the most important Supreme Court cases that we thought might be central to the case. The next morning, we received a call from Goodale and proceeded to The Times for our first meeting with our client. As we traveled uptown, I wondered if anyone at The Times knew that Bickel had never tried any case before and that I, the youngest partner in my firm, had never even been in the Supreme Court before.

Brotman: This must have been before dawn.

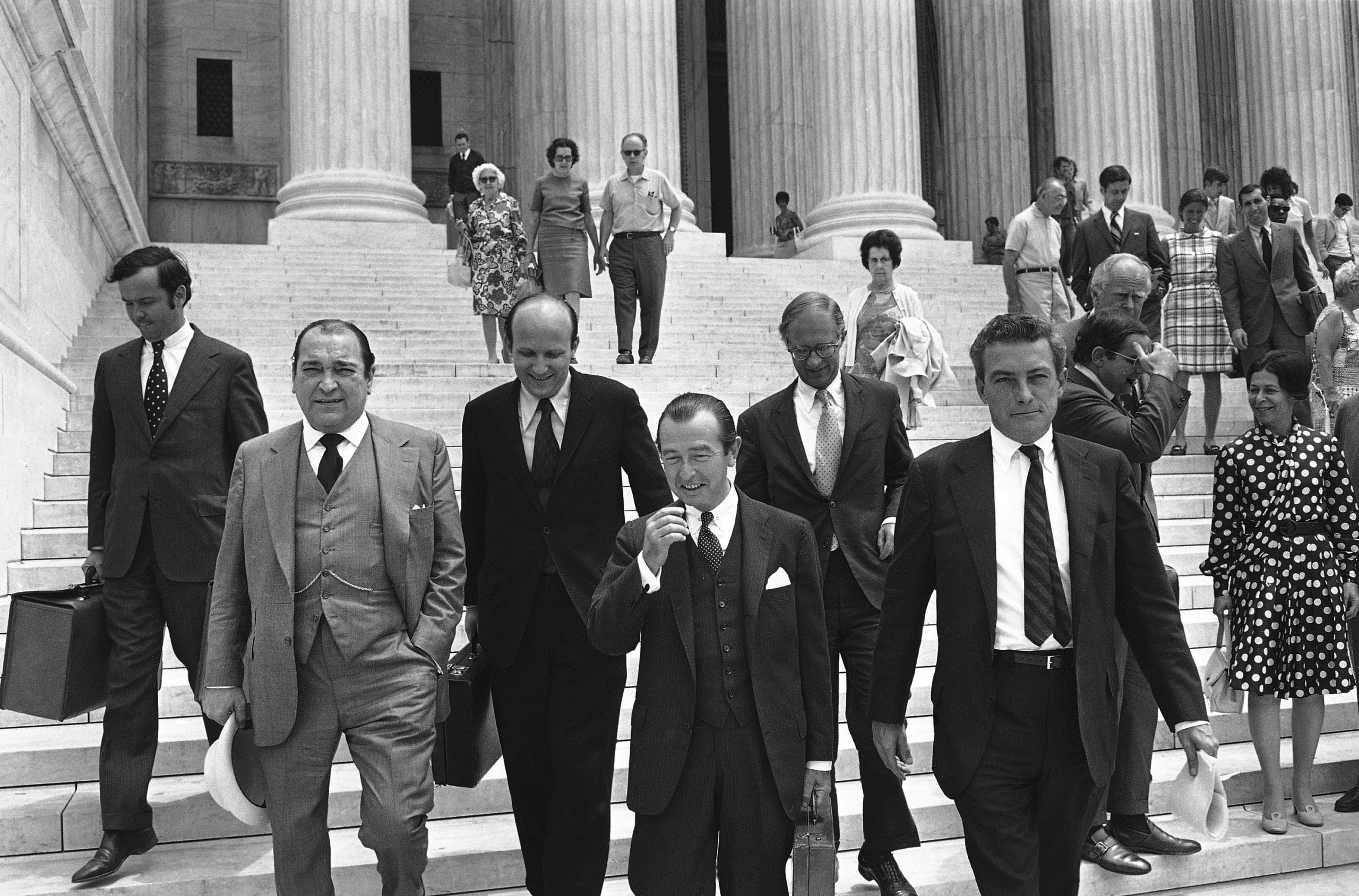

Abrams: Absolutely. And we read it for the first time. We went to The Times the next morning for a meeting. Neither of us knew anyone on The Times, but I knew a good bit by then and started talking about what could happen. The Washington Post also was in the picture at that point. During the meeting, a telephone call was received from the lawyer who headed the Civil Division of the US Attorney’s Office in New York, saying that the government was going to court at noon. We went to court and appeared before a brand-new judge, Murray Gurfein, just appointed by President Nixon. We went there with Jim Goodale, the general counsel for The Times.

It was noteworthy to us that in World War II, Judge Gurfein had been in army intelligence and therefore had had access to classified material. We were sure (and we were right about this) that his military service would be highly relevant, since it could put him more at ease dealing with classified documents and claims of harm from their revelation.

I remember Judge Gurfein saying, “We’re all Americans,” which we feared (but could not know) was a barb aimed at The Times and its lawyers. The government urged him to enter a temporary restraining order. Bickel argued that no such order had ever been entered and that doing so could not be consistent with the First Amendment.

The government was using language about irreparable harm. Judge Gurfein said to us, in effect, “Why don’t you give me a chance to study this? So why don’t you agree not to publish until a few days later?” Goodale called The Times. He was the leader on this. But the answer, which Goodale had urged and we all agreed with, was that for a newspaper, the status quo was the right to print, not enforced silence. The Times would continue to publish.

Judge Gurfein then entered the order of prior restraint based on the government’s representation of the highly classified nature of the documents, and that American POWs were being held. Publishing, the government argued, could interfere with getting them out.

We had a number of meetings at The Times during the unusually brief case (it lasted only fifteen days from start to finish) and the one I remember best was at the very beginning of it. It was a meeting chaired by Punch Sulzberger, The Times publisher, in which shortly after the meeting began, he said that whatever the decision of the court was, that The Times would obey it.

Tom Wicker, their Washington correspondent and columnist said, “Punch, I thought that’s why we were meeting, to discuss if we were going to obey the order. Let’s talk about it.” Bickel basically said this to them: “What this is all about, and what we are fighting for in this case, is obedience to law — in this case, the First Amendment. That means abiding by law even if you disagree with it.”

I offered a more strategic response, urging on them that if we violated a court order in the case and wound up in the Supreme Court, that the Court would be furious with The Times — doing so would make it far more unlikely that we would persuade jurists who were not fond of the press generally, and The Times specifically, to rule in our favor.

So everyone at the meeting signed off to obey the order but mount an aggressive legal challenge to it. Thereafter, we had the litigation. Bickel argued just about everything himself. My partner Bill Hegarty came to work with him on the secret stuff — national security stuff — which was heard in a secret session of the court.

Brotman: Take me behind the scenes as the litigation began to be organized at your end.

Abrams: From the very beginning of the case, we realized we had one particularly high hurtle to overcome. The nation was at war, American soldiers were dying, with others held as prisoners of war, and the Executive Branch was representing to the Court that further publication of the Pentagon Papers would do irreparable harm to the nation. In that context, why should the Court intervene? I kept thinking as the case progressed that if we were in the midst of World War II, and a similar issue had arisen that while a court might have ruled for us, it would not have wanted to do so and might well not done so.

One way to address those fears was to try to persuade the Supreme Court that the government was exaggerating the potential for harm from The Times’ publication. Accordingly, we obtained affidavits from high-ranking former State Department and CIA officials stating that publication of the sort of material in the Pentagon Papers was not really harmful to the war effort, that what they revealed was not weapons technology, plans of military operations or the like. We were helped, we thought, by the reality that what the Pentagon Papers themselves demonstrated was a pattern of government falsehoods through the years about the Vietnam conflict, a pattern that we did not quite say, but inevitably inferred, was continuing into the case.

The cross-examination by my partner William Hegarty of a chief military witness for the government was extremely helpful in this respect, since it showed that the witness was upset about even the least revealing information about national defense. At the same time, we sought to minimize any supposed harm from publication of the Pentagon Papers by the submission of a superb affidavit by Max Frankel, former Executive Editor of The Times, about well-established norms in Washington. Even classified information was commonly made available to journalists by government officials for a variety of motivations — personal and policy-related — which had the impact of significantly informing the public. The publication of portions of the Pentagon Papers, Frankel argued, was one example of that.

There were a number of hearings in the case, including a particularly threatening one that I argued. That was the government directing The Times to turn over the Pentagon Papers that they had, which we were immediately told would compromise the identity of the source because his fingerprints were all over it. At that point, Daniel Ellsberg was not visible and not known. His name was unknown to us, too. But we were told that the source could be discovered, so I argued on that issue.

At that time, The Times had another case in the courts in California on the issue of confidential sources. One of their journalists, Earl Caldwell, had been subpoenaed and was protected by a court order that was on appeal. That was one of the cases that went to the Supreme Court later, the case I mentioned that Bickel had been called in to write a combined brief for media companies.

So my argument was not to make us have to turn over the documents. Bickel came up with the idea: “Well, why can’t you tell them what documents you have, without actually giving them?” Which we did and which they promptly forgot. But it turned out to be really important. The Times would not have complied with that order, they would not have turned over the actual Pentagon Papers that they had, thinking that it would compromise the source. If that happened, then everything would have gotten off the tracks. The Supreme Court was not about to protect journalists who were violating court orders to judges. We would have a real problem when the case went to the Supreme Court.

Brotman: And you knew the Pentagon Papers case would be going to go to Supreme Court.

Abrams: We knew. But it was very fortuitous that we told the judges about what was in the documents without actually turning them over.

Brotman: It sounds like you all were on a 24/7 schedule.

Abrams: We were all working day and night. No one’s sleeping, and no one knows anything anymore. You forget things. I don’t mean now. I mean then.

Brotman: You had a relatively small legal team, right?

Abrams: Well, we had like eight people. But in terms of who knows this or that, it was very small. The government continued to maintain, throughout the case, that The Times had certain documents that were not on our list. But it’s not because they thought we lied; they paid no attention to the list we gave them.

Brotman: And in lightning speed, the case reaches the Supreme Court.

Abrams: It took fifteen days, from beginning to end. Bickel’s argument in the Supreme Court had one central moment. He thought, and I thought, that was when he was answering the question of Justice Potter Stewart, who asked in effect, “Suppose when we go back to our chambers and we read the Pentagon Papers, we find that publication of material at issue would result in the death of twenty American young men who simply had the misfortune to have a low number in terms of being drafted. Is your position then that we must allow you to publish?”

Bickel started, lawyers often do this, “That’s not this case.” That was true but it also was an answer that frequently irritates judges who know that and are posing hypothetical questions to explore the breadth of an argument. Finally, Bickel said that if this were the situation, then his dedication to the First Amendment would clash with his dedication to the security of the country. And yes, The Times would not publish that. That answer was viewed as such a sellout by the ACLU that they submitted a brief denouncing it. I thought they were wrong, terribly wrong, and that his answer was absolutely required for an advocate for The Times to make.

Brotman: Were you aware they were going to file that?

Abrams: Not in advance. The case came and went, it was over on June 30. We won six to three. I have been struck by the fact that even the justices who voted for us had been persuaded by the government that publication would do some harm. They were wrong about that. But basically they said the government had failed to prove that the amount of harm that would be done outweighed the First Amendment, so the near-total ban on prior restraints carried the day and we prevailed.

Brotman: How important was it that The Times was the client?

Abrams: It was very important that The Times was the client during the case. A less respected entity might well have lost the case. But even as to The Times, there remained the risk, as indicated by what some of the justices observed, that there could still be an Espionage Act prosecution of The Times after publication. In effect, the Supreme Court suggested if The Times wanted to take the chance that it was going to be indicted, you know, this remained a risk at that point.

Brotman: What advice were you providing about this potential criminal prosecution?

Abrams: We didn’t really have a strong view as to what would have happened regarding a charge of breaching the Espionage Act. We had argued to Justice [Thurgood] Marshall, who agreed with us on this, that the Espionage Act didn’t cover journalists reporting news in good faith. Marshall went along with that, but certainly Justice [Byron] White and Justice Stewart did not. That did not happen, though. So the case really was over.