This map was created by © J. Thomas McGlothlin.

Until recently, not many people around the world, or around the nation, had heard of the New Orleans neighborhood where I grew up. As a matter of fact, not many in Louisiana or in the Crescent City could find their way to the Lower Ninth Ward if they were forced to do so.

The Lower Nine, as we often call it, has been a bit of a forgotten land. If you had a business, church, home, friends or a school there, you knew how to get in and get out before dark. Otherwise, you might have heard something about it, but you didn’t want to know much, and you really didn’t have much reason to want to know much about our part of the city. However, for those of us who lived there for whatever length of time, it was home. It was where we kids played kickball, where neighbors lit paper Japanese lanterns at night, where we would watch the Holy Cross High School band or football team for entertainment, or catch crawfish in the canal or along the rocky shores of the Mississippi River.

Heck, when it got dark and the lights went on we, too, left—except we left the streets to go inside to the loving arms of our families, a delicious meal of red beans and rice, and the warmth of family fellowship.

The Ninth Ward might have seemed pretty bad to others, but we saw more good than bad. Like many other neighborhoods, we went with what we had.

Our Neighborhood

Most of us weren’t there because we wanted to be there but because it was what our families could afford. Some of us were trying to move on up to a better quality apartment or home in the Ninth. We could’ve been in a shotgun house in another neighborhood or the brick house we had in the Ninth. Some in the Ninth wouldn’t think of leaving. Some were trying to move on up to other New Orleans neighborhoods. When we were able, we moved to a tree-lined neighborhood called Gentilly just a few years later. Some we left behind were just struggling day-by-day, not thinking much about the future.

What’s been missing in a lot of the media coverage is a sense of who used to be in the neighborhood. I went to high school with a guy named Antonio Domino. He was named after his dad. His dad had another, more familiar name, however. Fats. Fats Domino. I remember going to their home after school and band practice sometimes and wondering why a man with a lot of money would have such a large house in our old neighborhood when he could live almost anywhere else. The real answer, of course, was because it was home. It was comfortable. They were with family and friends. Besides, another neighborhood might not have understood why Domino wanted a purple roof atop his home.

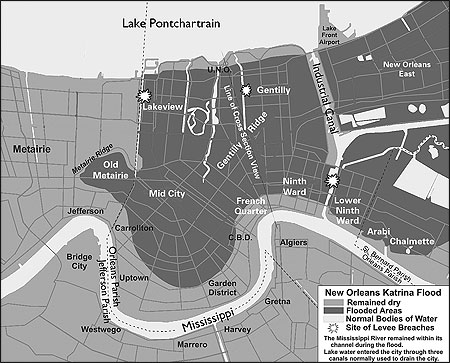

This section of one of the nation’s most prominent tourist cities is seldom visited by residents of other city neighborhoods or tourists. Water surrounds it on three sides: the mighty Mississippi River to the south, the beautiful Bayou Bienvenue to the east, and the sometimes stench-filled Industrial Canal to the west. It’s not that businessmen, government bureaucrats, journalists and politicians never found their way to our neighborhood. It’s just that whenever they came, they so frequently left without any real hope or promise among those they left behind.

Blacks and whites attended Semmes Elementary School, just a short walk down North Rampart Street from our home. People might forget that white folks used to live in the Ninth, too. They really did. Like us, they were working to provide homes for their families and working to make a better life. There were fine times at school. But this was the 1960’s, so there was definite friction. One of my sisters was called a nigger and bullied by some of the white kids who didn’t want her there. You see, the Lower Nine wasn’t always nearly all black.

My family wasn’t rich, and we weren’t poor. My dad was a newly minted PhD who landed a job as a professor at Dillard University, a small, historically black college where he and my mom went to school, met and fell in love. Though there were two parents and six kids, we always knew we’d eat dinner each day, wore nice clothes and shoes, and did a few family entertainment things. But money was tight, and the one-story house where we lived on Rampart Street was what we could afford. We kids felt good that we could live in a brick house. Cousin Lynne Aung lived right behind us with her husband. That made it even more special.

Sure, the impoverished neighborhood has had its share of crime, poor education, and worse. Still, some of us rose from the pressures to become reasonably successful. One of my brothers and one of my sisters are doctors. One brother is a mortgage broker and an independent businessman. A sister is a university professor of research library science. Another brother, like me, is a journalist. Oh, and Cousin Lynne is a successful psychologist in California, who once headed that state’s psychology association.

That hard-working mother of ours raised six kids and still managed to earn a masters and teach elementary education at the college level. That hard-working father of ours sometimes worked two jobs to keep everything going through our times in the Ninth, in Gentilly, and even after I left home for college. That man became a college president in his home state of Mississippi.

The Lower Nine has produced some famous names who have stayed in the neighborhood, some who have wanted to leave but couldn’t, and a bunch of black professionals like us who moved to the Gentilly, New Orleans East or West Bank neighborhoods. Post-Katrina, a lot of those professionals who have tried to make the old neighborhood more than it has been aren’t likely to return. Those who moved to other neighborhoods with fond memories of the Ninth Ward aren’t likely to return to the city. We’re talking about Catholic and public school teachers, firefighters, police officers, longshoremen, doctors and attorneys. Many of them have left the city for other parts of Louisiana, Texas and states beyond.

We always knew the city was below sea level. We even knew that we were lower than other parts of the city and expected flooding with heavy rains. If there were only puddles, no standing water, it meant the good Lord had granted us a reprieve. When heavy rains, tropical storms, or tremendous hurricanes like Hurricane Betsy in 1965 or Camille in 1969 hit New Orleans, we frequently suffered more than any other section of the city.

Our family’s parish church, St. David’s, was about seven blocks north of the Mississippi and 10 to 12 blocks to the east of the Inner Harbor Navigation Canal. I earned my Eagle Scout award at St. David’s. So did my brother, Ave. We made The Louisiana Weekly. I don’t remember making The Times-Picayune, the major daily. Far too often it’s the little “big” things like that that are indicative of what the media think is most important about our neighborhood and others like it. A short public bus ride away is the world-famous French Quarter. The quarter isn’t that far away, yet the neighborhoods are worlds apart.

Other city neighborhoods seemed to make the news for all kinds of reasons. Bad news. Good news. Breaking news. Feature news. When it came to our old neighborhood, however, it seemed that we only made television or made the paper when someone was shot and killed or when there was enough water to show cars slowly driving through the floodwaters.

Three generations of the Sutton family gather in a sibling’s New Orleans home in 1992. Will Sutton is second from right, standing.

The Vital Role Journalists Can Play

Our neighborhood didn’t get a lot of local and national media attention, but we should’ve. Our neighborhood should’ve gotten more national media attention well before Hurricane Katrina hit the Gulf Coast. It certainly deserves more media attention now that Katrina and Hurricane Rita have devastated so much of the Lower Nine. With more media attention, more journalistic examination of the pros and cons of razing hundreds of businesses and homes in this special part of the city, the news media can be at the center of helping New Orleanians and Louisianians decide whether it is worth it to start from scratch or save what can be saved and make some progress.

There’s much debate in the press about public journalism, civic journalism, and other forms of journalism geared toward getting citizens and readers involved in the decision-making. Journalists have some responsibility. Maybe even a lot of responsibility. As we look for what “sells,” improving the human condition doesn’t sell as well as news where there is clear conflict, news where there is immediacy, news where more affluent people are affected. Even so, The Times-Picayune, The Advocate in Baton Rouge, and other state newspapers and television stations should force the connected and the powerful to discuss these options with the people whose lives would be affected most.

I fear that most New Orleanians won’t have a say about the Crescent City’s future. They won’t have a say about how the city is rezoned, which parts of the city are razed, which parts are revitalized, and which parts get special jobs attention. It doesn’t have to be that way if the news media step up and make these issues important local, state and national issues. This situation isn’t a matter for local businessmen and politicians. It’s a matter of great national importance—and it should be covered that way. The media should work to show readers and viewers everywhere why they should care about what happens to New Orleans. Everyone will want to know about future Mardi Gras celebrations, the French Quarter, and whether the annual Jazz Fest will continue, but this is a much bigger story, one that deserves deeper, critical reporting. Without that type of coverage from within and outside of Louisiana, the Lower Ninth Ward and all of New Orleans will never be in the best interest of all. What I knew and what others have known will never be the same. That might be okay with me, depending on whether the media does its job and whether the people have a chance to have a say. Thank goodness the local daily, the Times-Picayune, has been brave enough to start some serious digging already.

What’s happened in the Lower Ninth Ward pre-Katrina is not that unusual. It isn’t unlike so many other urban areas or sections of cities like Camden and East Orange, New Jersey; East St. Louis, Illinois, and so on. These other situations simply haven’t gained the same amount of coverage, at least not nationally. Things happen there every day and every night that get little or no coverage unless and until a “visitor” to the neighborhood is hurt or killed or unless and until there is a major disaster that just cannot be ignored.

It’s a shame that it takes something horrible to get attention for people who really need help. Maybe the media can bring more attention to the nation’s Lower Ninth wards and thereby shine a spotlight on the nation’s economic and racial parity, diversity that goes beyond skin color and ethnicity, and go deep enough with investigations and research to show readers and viewers why they should care, how they are being affected, and how they will be affected if somebody, somewhere doesn’t do something—and soon.

Will Sutton, a 1988 Nieman Fellow, is the Scripps Howard Visiting Professional at the Scripps Howard School of Journalism and Communications at Hampton University in Hampton, Virginia. A Hampton graduate, he is the director of the school’s Academy of Writing Excellence (AWE). A native of New Orleans and former resident of the city’s Lower Ninth Ward, he is at least a fourth-generation New Orleanian who lives in Cary, North Carolina with his wife and son. He is a former president of the National Association of Black Journalists and a cofounder of what became UNITY: Journalists of Color, Inc..