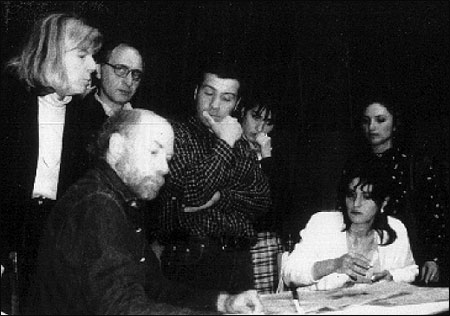

Trainer Robert Tonsing leads a workshop for Georgian journalists in Tbilisi in May. Tonsing presented his workshops as part of the ProMediaII-Georgia program, sponsored by the U.S. Agency for International Development and administered by the International Center for Journalists. Photo by Irina Abjandadze.

Roman Gotsiridze, head of the Georgian Parliament’s Budget Office, has a brainstorm for saving the independent news media in this fledgling democracy: government financing. To Americans this is heresay. By definition, a strong press is not dependent on government. But after several years of training journalists in former Soviet-controlled nations, it is easy to see why reformers like Gotsiridze embrace such chimera.

The easy part, it is now clear, was toppling communism. The hard part is creating a functioning democracy on top of the rubble. Georgians must build virtually every institution from scratch—and that includes news media that provide reliable social, political and economic information.

The best place to start looking for problems is in the economy. The early transition to a market-driven system eliminated government-guaranteed jobs, health care, and housing. Nearly two-thirds of Georgians now live below subsistence levels. Few can afford 20 or 25 cents for a newspaper, let alone the products sold in them. Advertisers have little incentive to buy advertising space. Four or five years ago, the newspaper Droni appeared six times a week with three or four pages of ads in each issue. Now it appears four times a week with a page or less of ads each time. Compounding the problem is the media’s lack of experience selling ads or providing fair, balanced reporting. Journalists often see newly won press freedom as an opportunity to express their own opinions, not facts.

Several newspapers in the capital city of Tbilisi had a circulation of 300,000 or more during the first heady days of freedom. Today, none of this city’s eight newspapers has a regular readership of more than 5,000; a dozen or so have even smaller audiences. “We were very independent four or five years ago,” a worried newspaper editor says. “But now we are hardly surviving.” Reporters’ salaries typically amount to less than $150 a month, hardly a wage to inspire dedicated service. It is less surprising that some journalists take bribes than that some do not.

While media are not profitable, business and political leaders are eager to invest in them. These “dark forces,” as Gotsiridze calls these owners, finance news organizations in order to promote their own agenda. When bosses want access to the press, he says, they buy one. This summer a government official raised a furor by suggesting that a television journalist leave the country to avoid assassination. Heavy-handed press treatment by the government, however, is rarer in Georgia than in some nearby countries.

Belarus’s President Aleksandr Lukashenko pines for the good old days when he ran a collective farm. The head of his state Committee on the Press, whom I interviewed in 1998, reprimanded newspapers that accurately reported unpleasant statements by the weak political opposition. After three warnings, he said, the courts could close the paper. Meanwhile, Russian journalists critical of the government have been beaten or killed.

Georgia, however, epitomizes the dysfunctional, uncivil society that emerges when journalists cannot do their jobs adequately. Without accurate and timely news, rumor and suspicion rule. The euphoria over freedom gives way to cynicism. When foreign organizations make grants to local good-government associations, the common Georgian reaction is that someone had a special in. Jockeying for a place at the foreign aid trough is intense—and creative. One of the most novel new organizations is the Association of Young Grandmothers. Outright corruption is rampant. Police officers shake down motorists in front of the Parliament. President Eduard Shevardnadze is widely seen as tolerating corruption and helping his family get its share.

Taxation, as new to Georgia as a free press, is haphazard and dishonest. Tax collectors often pocket revenues. Fear of becoming visible to the taxman discourages businesses from advertising.

Because he believes that an independent press is crucial to curbing corruption, Gotsiridze concocted his media-financing scheme. Parliament, however, cannot possibly sustain every worthy news operation. And who is to say who is worthy? Members of Parliament will do the sensible thing and support newspapers that support them.

The World Bank, which is promoting economic reform, tried its own version of Gotsiridze’s idea through a loan to the Georgia government to create an English-language newspaper, EcoDigest. Ken Jacques, a former reporter for Congressional Quarterly and CNN who became a bank-paid consultant to the central government, is the author of the idea. EcoDigest provides better than average salaries, aggressively advertises itself on bus billboards, and concentrates on sound economic reporting. Even so, circulation is only 2,000. Many Georgians are suspicious of ties to the government.

Both Georgian and foreign critics say the bank’s venture sets a bad example. The best outcome, Jaques admits, is for a private investor to buy EcoDigest and build on its solid approach to news.

Meanwhile, Gotsiridze remains in his cramped but tidy office thinking of ways to bolster a free press. Parliament could vote to exempt media from taxes, although he worries that might encourage media companies to do what the tax-free Writers’ Union does. It imports beer, cigarettes, mushrooms and gas, which it then sells at a handsome profit. His plans to curb the Writers’ Union include stopping direct funding for that body and giving the money to individual writers.

The only true road to a free press is not government financing but patience. In the early United States republic, the press was wild and irresponsible. The turning point did not come until the mid-19th century, when media owners realized that the best way to sell newspapers to the burgeoning middle class was through fact-based reporting. Even then, sensational journalism continued in many newspapers for decades.

Young Georgian journalists, especially, are hungry to learn the skills of factual reporting and eager to find ways to sustain it financially. On my last day in the regional city of Telavi, three enthusiastic young women showed me a plan for creating a local news report that could be inserted into a newspaper. They hoped that a Tbilisi publisher would give them financing in exchange for better entree to Telavi.

Enterprise like this was the engine of our own press system. With a little luck, Georgia’s will mature faster than our own did.

“What I have learned,” the World Bank’s Jacques says, is that “if you chip away at it, you have done a damn good job.”

John Maxwell Hamilton, a veteran foreign correspondent who has trained journalists throughout Europe, is dean of the Manship School of Mass Communication at Louisiana State University.