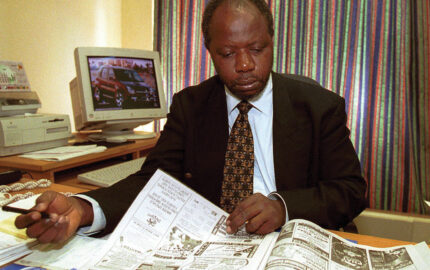

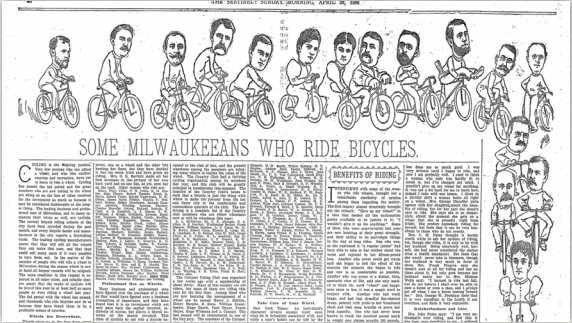

In the 1890s, at a time when many women didn’t dare, Agnes Wahl climbed on her bicycle and pedaled along the streets of Milwaukee. The cycling craze had swept the country, and for women it offered more than the thrill of being on two wheels. Women tossed their corsets and layers of petticoats and headed to meetings, jobs, school without being dependent on a horse, a carriage—a man. As Susan B. Anthony said at the time, bicycling had “done more to emancipate women than anything else in the world.”

Pedaling along those same Milwaukee streets was another adventuresome, forward-thinking spirit: Lucius W. Nieman, who went from folding newspapers for the Waukesha Freeman when he was 13 to becoming editor of the newly founded Milwaukee Daily Journal, at age 24.

Agnes and “Lute,” as he was known to friends, may have passed each other on their bikes as he was heading to work—he biked back and forth from his room at the Milwaukee Club—and she was off to a meeting of the French Club, of which she was the president, or one of her many other civic activities. Maybe she waved him down to invite him to the latest opera performance at her house, where Lucius had become a frequent guest in the mid-1890s.

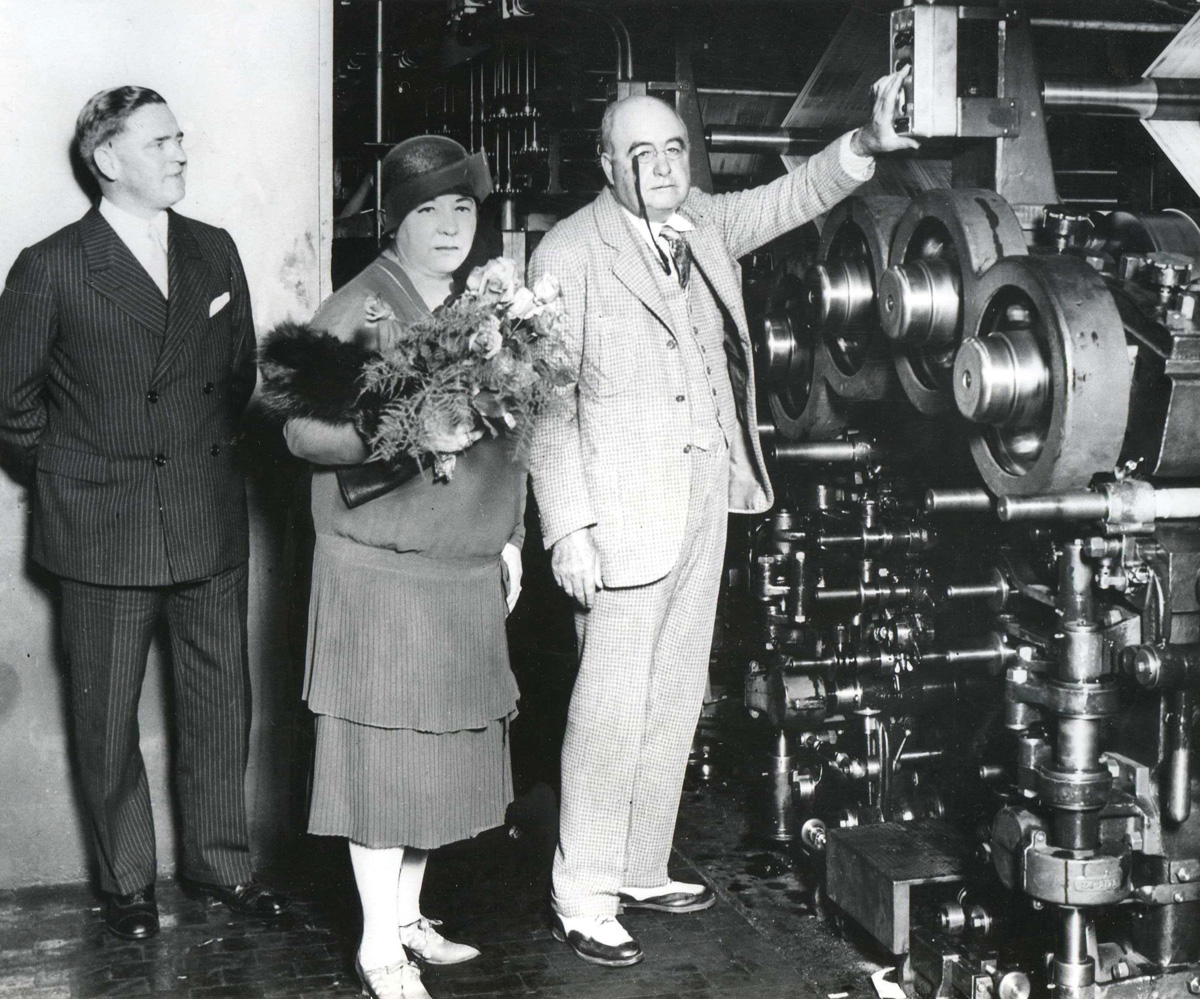

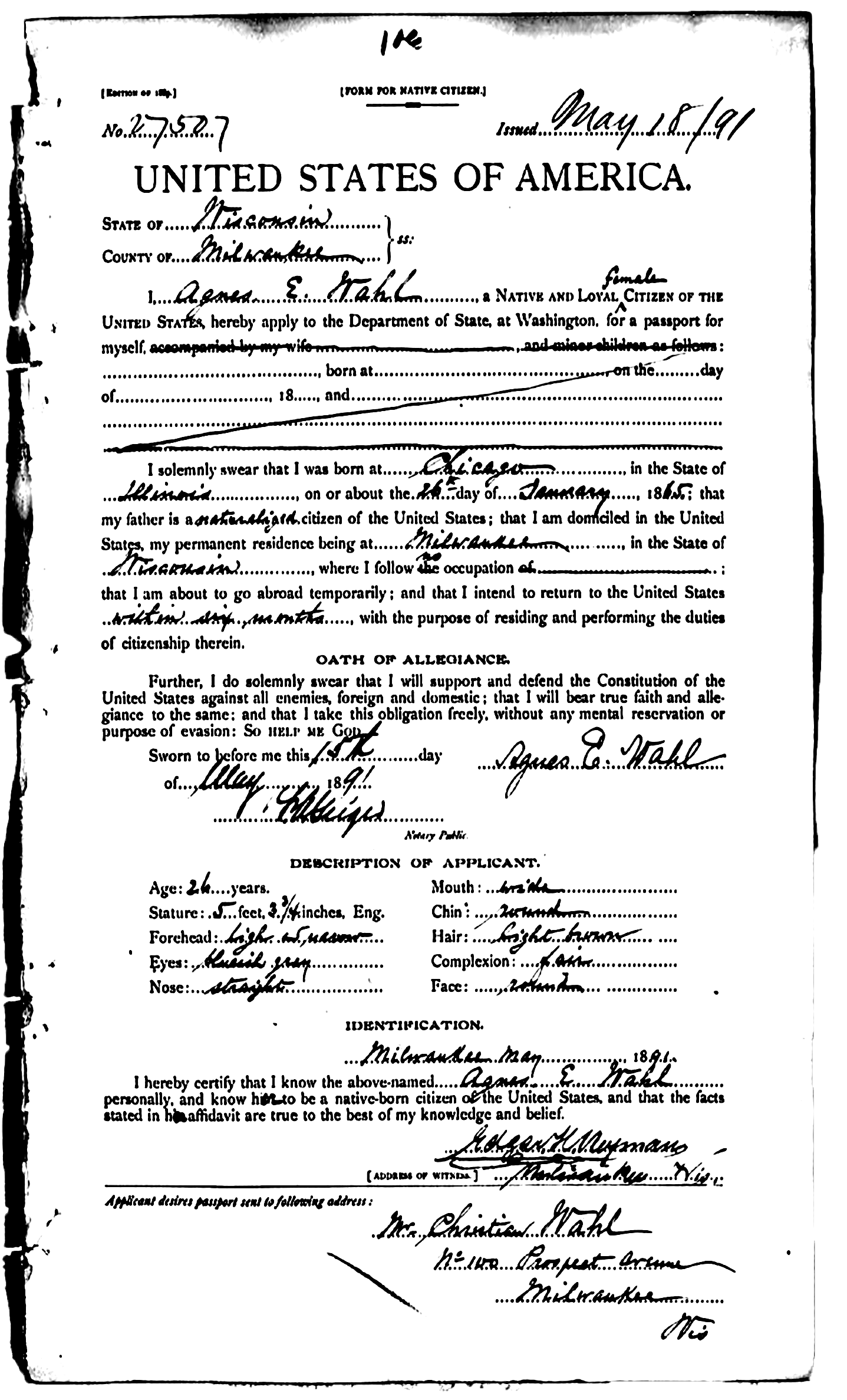

The truth is, we know little about their relationship and the woman without whom there would be no Nieman Foundation. Only two photographs of Agnes, who stood just under 5 feet 4 inches with light brown hair and bluish-gray eyes, are known to exist: One is a photograph of Agnes and Lucius beside a printing press, probably when she was in her late 50s or 60s; the other is from a collage of photos published in the Journal in 1916 under the headline, “Prominent Women of Milwaukee Co-operate for the Success of Great German-Austrian Bazaar.” The Milwaukee Journal itself includes only shards about her social life, her civic responsibilities, her travels. We don’t even know her exact date of birth. Census records from 1870 and 1880 suggest she was born in 1860 or 1861, but a passport application lists her as born “on or about” January 26, 1865. The longest piece of writing about Agnes that has turned up is the front-page obituary that ran in the Journal in 1936.

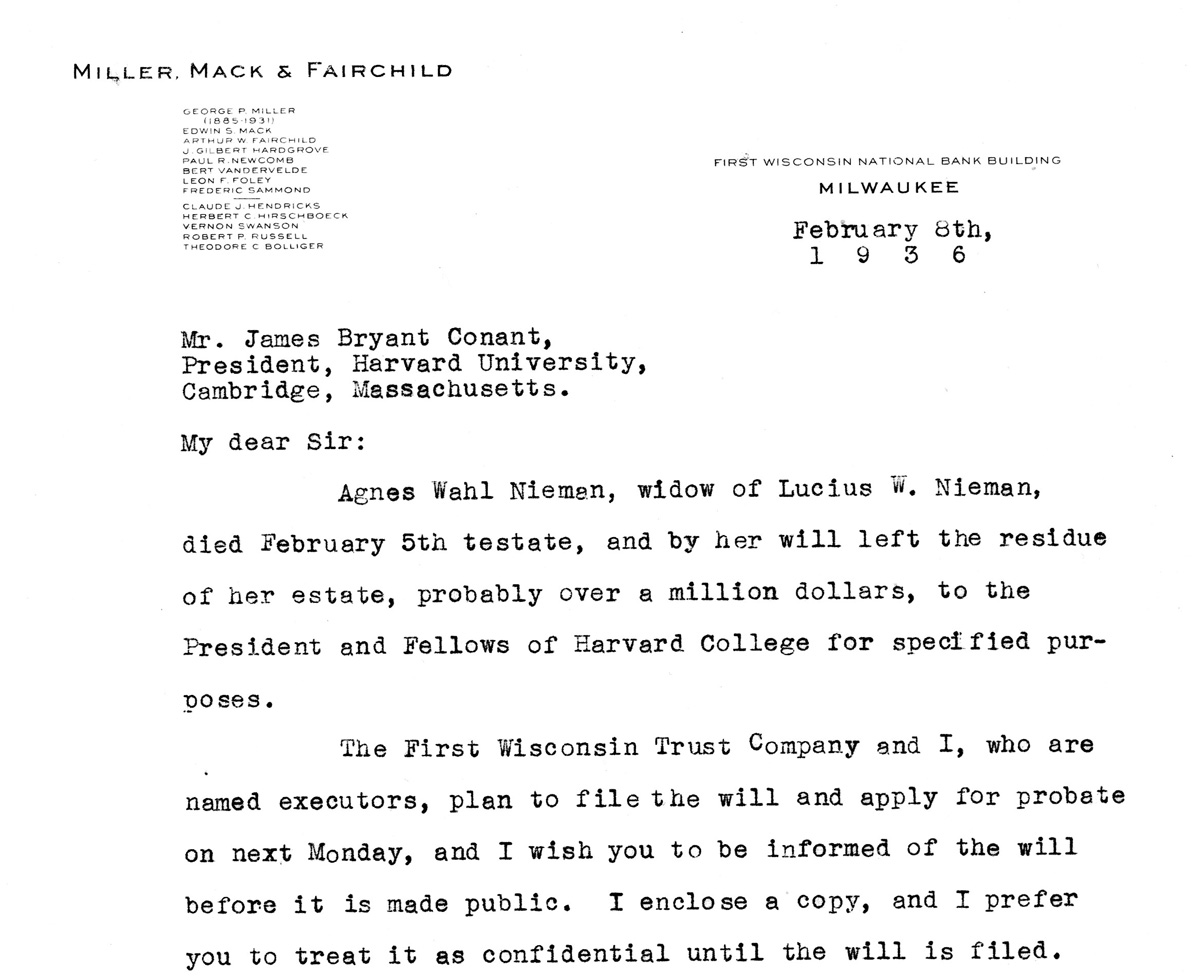

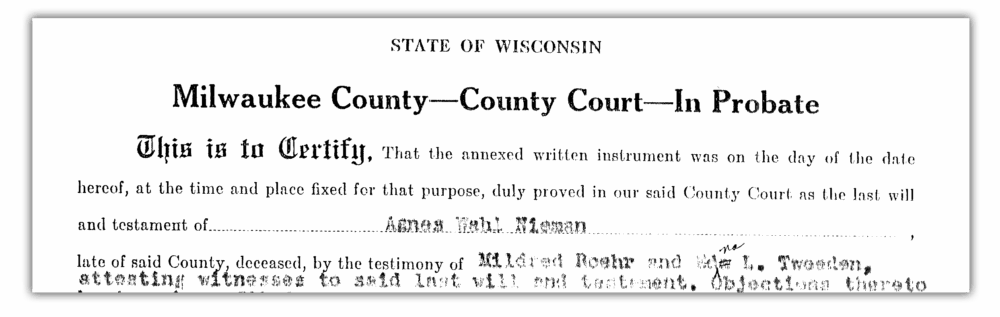

Harvard certainly did not know about the widow of Lucius Nieman when the president, James B. Conant, received a letter from her lawyer announcing that Agnes had named the university as the principal beneficiary of her estate, in her husband’s memory. Conant was not, in fact, enthused about the Milwaukee heiress’s desire to educate a bunch of journalists from around the United States at his elite university.

And it almost didn’t happen. The idea to leave money to Harvard—which relatives later contested in a heated court battle—arose in the final days of her life. If things had gone just slightly differently in 1936, there would be no Nieman Foundation—not at Harvard, not anywhere.

Agnes Elizabeth Guenther Wahl was born in Chicago, the eldest of three daughters of wealthy German-Americans, groomed with the impeccable manners, easy conversational skills, and passion for the arts that suited the balls, garden parties, cotillions and teas her family frequented.

Educated largely by governesses, Agnes spoke three languages and read the classics of German and French literature. Later she studied in Paris with Mathilde Marchesi, a German mezzo-soprano who trained many international opera stars.

Music had been central to the Wahl family for generations ... In her teens, Agnes studied in Paris with Mathilde Marchesi, who trained many international opera stars

Music had been central to the Wahl family for generations. Agnes’s grandfather started the Milwaukee Musical Society in 1850, after the family emigrated from Germany. (Both Agnes’s mother’s and father’s families were political liberals and active in German politics before leaving for the U.S.) Her father had a fine tenor voice, while Agnes was an alto and her sister Hedwig, a soprano. Both sisters sang as soloists in Beethoven’s Mass in C Major at Easter services, and Agnes performed in a local production of “The Mikado.”

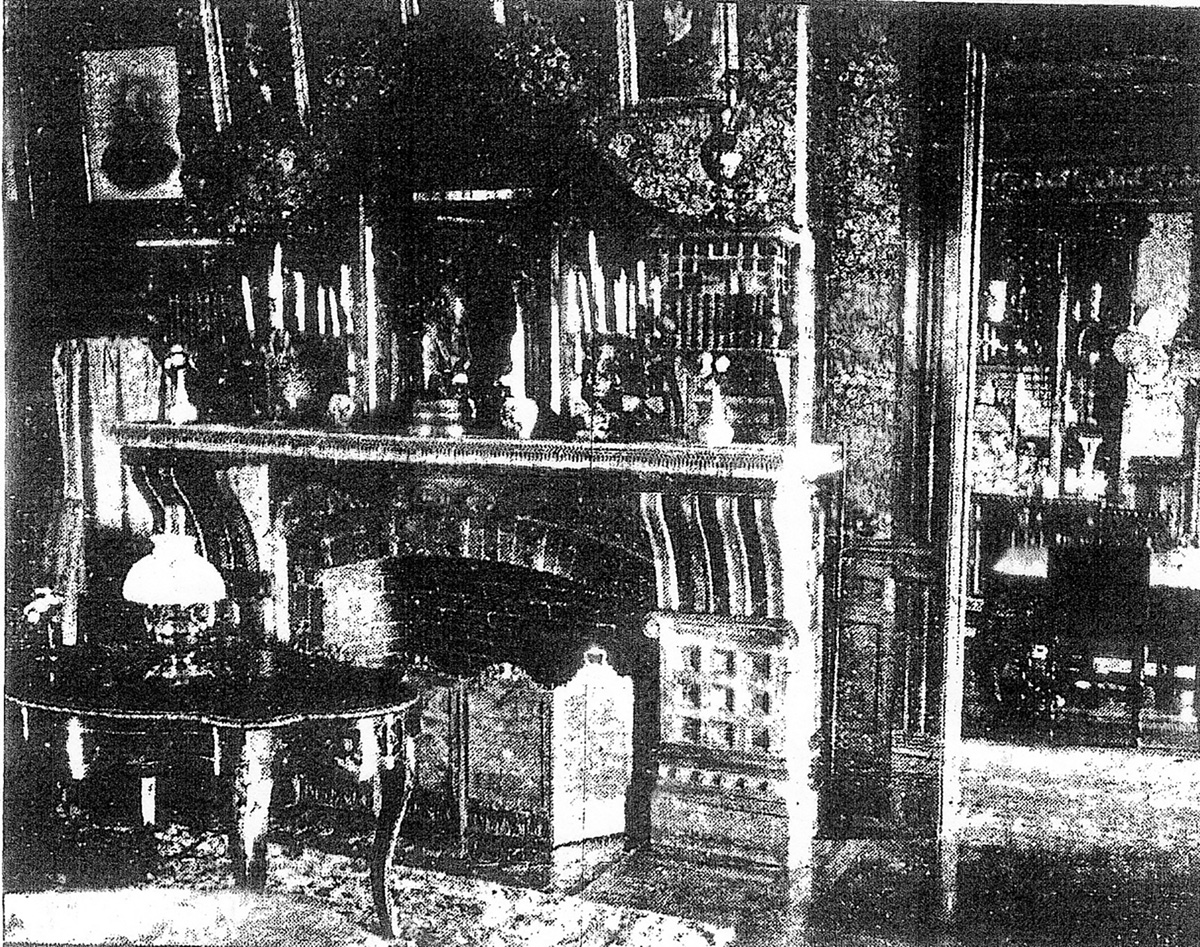

It was a heady time to be a German art lover in Milwaukee. The city was known as the “German Athens of the West” at the turn of the century. Art and music filled local theaters and homes of families like the Wahls. The house was one of the most magnificent along Milwaukee’s Gold Coast—a three-story brick and stone Victorian with 20 rooms, a wide entryway, views of Lake Michigan, and walls lined in stamped leather. Throughout were treasures from around the world: wood carvings from Switzerland, a bison head (reputed to be one of the largest in the world), tapestries and other artifacts from Germany, China, Japan, Bohemia, Switzerland.

An Unexpected Bequest

Harvard president James B. Conant had never heard of Agnes Wahl Nieman before he got word in 1936 that she had made a major gift to the college. It is not clear why she chose Harvard, but her attorney Edwin S. Mack, who was a graduate of Harvard College and Harvard Law School and an active member of Milwaukee’s Harvard Club, may have suggested the bequest.

With its grand rooms, the house was ideal for entertaining. Composer and conductor Walter Damrosch, who would later conduct the New York Symphony Orchestra, came to town with a German opera company and presented excerpts from a Wagnerian opera at the Wahl home. Painters, sculptors and other artists stopped by for drinks, dinners and conversation. And local groups, like Le Circle Francais, performed monologues, comedy acts, and songs in the house. At dances, the sounds of Clauder’s Orchestra, one of the top bands in the city, filled the Wahl ballroom.

Like her father, Agnes had a heart for adventure. Before she was married, she had traveled to Cuba, France and Germany, as well as extensively throughout the United States

Like her father—whose search for gold took him to California, Australia and Peru before he started a successful glue business in Chicago—Agnes had a heart for adventure. Before she was married, she had traveled to Cuba, France and Germany, as well as extensively throughout the United States. Later, she favored horse races—betting on horses behind her husband’s back—and became a fan of boxers, thrilled when she got to meet Jack Dempsey at a hotel in Coral Gables, Florida.

Also, like her father, Christian Wahl—a former Chicago city council member and later, most notably, Milwaukee’s “father of the parks,” overseeing the development of Milwaukee’s expansive public grounds—Agnes had a strong civic spirit. She was the financial secretary for the board of the Wisconsin Humane Society, which aided animals, and a volunteer with Milwaukee Children’s Hospital and a local “fresh air” organization that provided rural escapes for impoverished city kids. Those public interests may have, many decades later, influenced her to give much of her estate to an institution where it could make a long-lasting public impact.

Perhaps all her civic and social activities, as well as the financial means of her parents, with whom she lived, alleviated any rush to become a wife. She was somewhere between 35 and 40 when she married Lucius, many years older than the average age for U.S. women at the time. She may have also gotten cold feet after watching her younger sister’s marriage. In 1893, her sister Hedwig married Arthur Cyril Gordon Weld, a musical director (and a columnist at the Journal) who had fled Boston for Milwaukee after a broken marriage. Though Agnes’s parents were opposed to the marriage, the wedding took place, as did a divorce several years later when Weld abandoned Hedwig, set off for New York, and fell in love with an actress.

If Agnes and Lucius were already a romantic couple at Hedwig’s wedding (Agnes was the maid of honor, Lucius a groomsman), they certainly took their time, another seven years, before getting married themselves. Perhaps Lucius was frustrated with the long courtship in 1895 when he, along with other bachelors at the newspaper, wrote small observations on love in The Milwaukee Journal: “It is sometimes discouraging but persevere even though you seem to be bumping your head against a stone wall.”

But the days of frustration may have ended by 1897, when the society pages bubbled with references to Lucius and Agnes attending intimate lunches at the country club, dinner parties, and other social events throughout the city.

Then on November 28, 1900, in the drawing room of the Wahl mansion, Agnes and Lucius were married. She had a sapphire and diamond engagement ring. Hedwig was her matron of honor. Walking down the aisle ahead of the bride was a group of children, including 4-year-old Cyril Weld, Hedwig’s only child, whom Agnes would later come to regard as a son. The newlyweds soon moved into what’s known now as The Montgomery House, a Queen Anne home, more modest than her parents’ estate and a couple blocks from Lake Michigan, where Agnes always preferred to be.

The Wahls of Milwaukee

In the decades after she became Mrs. Nieman, it is unclear how much Agnes kept up with civic organizations. Though she wasn’t directly involved in running the paper, she was sometimes her husband’s adviser and sounding board.

Lucius joined the Journal with the goal of publishing news free of political bias and yellow journalism. He wanted a paper that, as he put it, “never cared about classes, but about people.” In the early months after the Journal launched, 71 people died in a fire at the city’s leading hotel, the Newall House. While other newspapers called it an unavoidable tragedy, the Journal said the building was a known “firetrap” and denounced the owners for greed and criminal negligence. Later, when some newspapers supported Wisconsin’s Bennett Law, the Journal criticized it for making teaching foreign languages illegal in grade schools. The Journal also waged battles on issues like municipal home-rule, the right of cities to formulate their own local policies. Then, in 1919, the newspaper won its first Pulitzer Prize, for Public Service, for its stance against Germany in World War I, which the committee cited as particularly brave given the newspaper’s pro-German constituency.

Even if Agnes didn’t have her hand in major newspaper decisions, she did know a few things about journalism from firsthand experience. In 1895, before she married, she was part of a group of women who persuaded Lucius to turn his paper over to them for a women’s charity edition. Agnes was in charge of coverage of Lake Park, albeit a conflict of interest given that her father oversaw the development. The edition was an enormous success, selling enough ads for a 56-page paper, the largest printed in Milwaukee at that time, earning more than $3,700 for the Milwaukee Welfare Fund.

Years later, Agnes continued to keep her eye on certain aspects of the newspaper. Pity the reporter who misused French or German in the Journal, only to have it corrected by Mrs. Nieman, who knew both languages expertly. And if a street vendor’s horse was suffering in the hot sun, Agnes, who cared passionately for animals, did not hesitate to reprimand him. If that didn’t lead to immediate action, she called her husband at work. “If we don’t do something about this,” Lucius would tell his staff, “I can’t go home tonight.”

Otherwise, Agnes remained committed to the arts, frequenting museums and exhibits and collecting art by both famous and lesser-known artists. She also took up golf, and together she and Lucius won multiple local tournaments.

But the tight-knit Wahl family, to whom she was devoted, had slowly disintegrated in the two decades after she married. The year after her wedding, her father suffered a heart attack in a streetcar near his home and was carried into a drugstore, where he died in minutes. Her mother died eight years later. By 1926, both of her sisters were dead.

Agnes’s remaining closest blood relative was her nephew, Cyril, Hedwig’s only child. He had been a constant presence in Agnes’s life. As the only grandchild of Christian Wahl, Cyril was chosen at age 7 to unveil a statue of his grandfather at a 1903 dedication at Lake Park honoring his service. The bronze bust on a red granite base has since been moved to Wahl Park.

Cyril also worked briefly at the Journal, and Agnes encouraged him to return to Milwaukee for a newspaper career. But Cyril had his heart set on acting and lived in Los Angeles and later New York City. Still, he visited Agnes, who provided a monthly allowance and together with Lucius threw him parties and invited his friends to their home.

In the early ‘20s, Lucius suffered a stroke and Harry J. Grant, originally the business manager, stepped in to edit the paper

Then, in the early 1920s Lucius suffered a stroke. Over the next years he was seldom in the newsroom more than an hour a day. Harry J. Grant, originally hired as the business manager, stepped into his place.

Aside from winter escapes to California or Florida, those final years for Agnes and Lucius were quiet ones. They didn’t socialize as much as they once had. Instead, they often took drives around the city to view the parks and the lake. They moved into an apartment on the top floor of the eight-story Knickerbocker Hotel with views of the water and enough room for Agnes’s extensive collection of music books and sheet music. In her living room hung a portrait of her mother by Heinrich von Angeli, one of the finest court painters in Europe. Agnes bequeathed it to the Milwaukee Art Museum, where it currently hangs.

Lucius Nieman died at home on October 1, 1935, after spending the last two years of his life largely confined to their apartment. In the painful weeks afterward, Agnes wondered aloud how other widows carried on.

Then a breath of good news arrived when her nephew Cyril landed his first Broadway role. On October 28 he opened in the play, “Dead End,” a story of gangsters in New York City. But two months later, Cyril came down with pneumonia. Agnes left by train in early January with her personal nurse and her close friend, W.W. Rowland, a longtime member of the Journal staff who Agnes sometimes referred to as “son.”

At Lister Hospital in Manhattan, Agnes became Cyril’s advocate, overseeing his treatment. She told his doctor to spare no expense in caring for her nephew. Two days later, she was sitting by his bed when Cyril died. He was 39.

Agnes brought her nephew’s body back home by train. She planned his funeral, down to the pallbearers, the yellow roses, and the music, including both Agnes and Cyril’s favorite, Brahms’s lullaby “Wiegenlied,” and the traditional hymn of the Wahl household, Mendelssohn’s “Es ist bestimmt in Gottes Rath” (“It is Ordained by God’s Decree”). Both pieces would also be sung at Agnes’s funeral.

Two weeks after Cyril’s death, Agnes’s doctor ordered her to bed. She had suffered from kidney problems, high blood pressure, and edema in her ankles. Now the deaths of the two people she loved the most had weakened her further. “There is nothing to live for,” she confided to her nurse.

She was anxious, too, about Cyril’s will. No one could find a copy, though she and Cyril had talked about leaving their estates to each other. Given that he had no wife and no children, Cyril’s money would pass to two half-sisters he had never known. Meanwhile, the will Agnes created in 1932 left the bulk of her estate to Cyril. She was desperate to rewrite it and retain control over her money.

She talked to her friend Rowland about creating a memorial to Lucius. She also called her lawyer, Edwin S. Mack, who was the trustee of Lucius’s estate.

No one but Agnes and Mack knows exactly how those conversations unfolded. But at 4 p.m. on Saturday, February 1, 1936, Mack brought over the new will. Before he arrived, Agnes asked her nurse to bring her reading glasses and straighten her hair. She and Mack spoke for about an hour. When he left, Agnes told her nurse “half my trouble is over.” She believed her health would now improve.

That same day, Lucius’s niece, Faye McBeath, who had worked at the newspaper since 1916 and to whom Agnes would leave her engagement ring as well as other jewelry and her silverware and gold, spent more than an hour with Agnes, though McBeath said they never talked about the particulars of the new will. The next day, around 10 a.m., Agnes telephoned Rowland, telling him they would read over the will together the next day.

It never happened. Agnes came down with a fever and was diagnosed with pneumonia. On February 5, 1936, four months after she lost her husband and less than a month after Cyril’s death, Agnes Wahl Nieman died at 6:20 a.m. In her bedroom stood two urns, which she had adorned with roses days before: One contained the ashes of her husband, the other of her nephew.

A Heart for Adventure

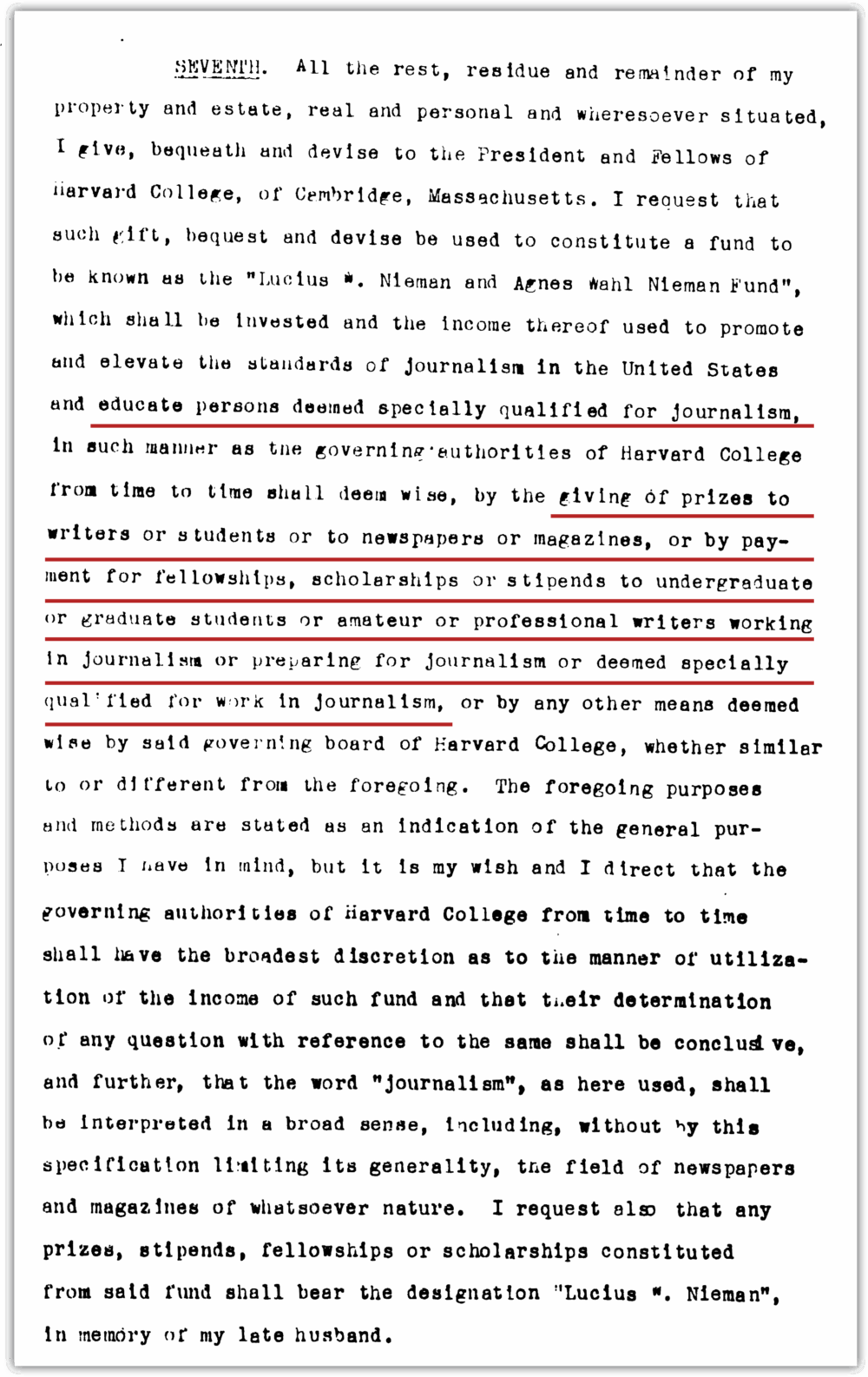

Agnes’s story, of course, did not end with her death. The will that she changed four days before she died now left the largest portion of her estate to Harvard University “to promote and elevate the standards of journalism in the United States and educate persons deemed specially qualified for journalism.” Records from the Harvard treasurer’s office indicate that Agnes’s gift came in over a number of years and totaled about $1.4 million

Claiming she was not of “sound mind,” three of Agnes’s relatives contested the will in which she made her bequest to Harvard

It wasn't initially clear, however, that Harvard would get that money. Four months after Agnes died, three relatives—two of whom she hadn’t seen in years—claimed she was not of “sound mind” and that she was an alcoholic when she signed the will. (Agnes did like a daily gin and grapefruit juice.) There were also suggestions that Mack, her lawyer, who graduated from Harvard College and Harvard Law School and was actively involved in Milwaukee’s Harvard Club, influenced her to give her money to his alma mater.

For seven days in a Milwaukee court (it was one of the largest will contests in local courts at that time) a parade of Agnes’s household workers—her chauffeur, two nurses—and various doctors (some of whom had never laid eyes on Agnes) as well as Rowland and Lucius’s niece, Faye McBeath, testified about her mental health, her physical ailments, her intentions. Rowland noted she was an unhappy woman after her husband’s death. But no one provided compelling evidence that she was an alcoholic, unstable, or not mentally capable of making her own decisions.

At the conclusion of the trial, the judge said that he believed Agnes’s decision to give money to Harvard was, ultimately, her own. He pointed out that Harvard was not the only beneficiary: She had left money to several loved ones and organizations, including to the humane society and the children’s hospital, much as she did in her original will. As for Harvard, the judge thought Mack was not guilty. “A lawyer who draws a will for a client,” the judge wrote, “is not a mere draftsman … It is the duty of a lawyer, and I assume that is what he is retained for by the client who expects to make a will, to give the client the benefit of his advice and judgment and if you please, if asked for, suggestions.”

How it All Began

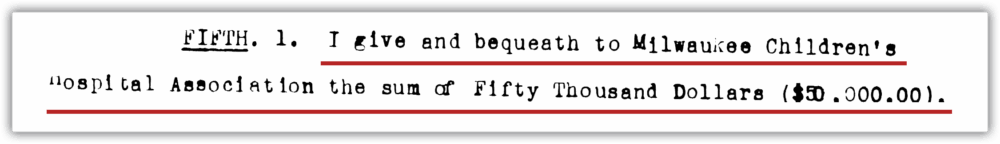

Apart from the bequest to Harvard College, Agnes gave $50,000 to the Milwaukee Children’s Hospital and $6,000 to the Wisconsin Humane Society. In addition to establishing a $50,000 trust fund for a cousin, Agnes willed a total of about $140,000 to nearly 20 other relatives, friends and employees. The gifts ranged in size from $500 to one of her household employees to $25,000 for Milwaukee Journal automobile editor W.W. (Brownie) Rowland.

Agnes stipulated that the rest of her estate be given to Harvard College for a “Lucius W. Nieman and Agnes Wahl Nieman Fund.” She did not stipulate that the money should only benefit men. That was a decision Harvard made. In a letter to the Nieman Foundation in 1938, Gladys Hobbs, a reporter in Salt Lake City, Utah, criticized the men-only policy as “anything but scientific” and “unworthy of Harvard.” She wrote, “The type of reporting I have done is unlimited and my ambition is great, but I am not allowed to apply because I am not a man.” It wasn’t until the eighth class of Nieman Fellows was named in 1945 that women were admitted. Harvard Medical School began accepting women as students that same year.

Though she suggested a number of uses for the money, Agnes made it clear that Harvard should have “the broadest discretion” in spending the funds. In addition, she stipulated that “journalism, as here used, shall be interpreted in a broad sense” and not limited to newspapers and magazines.

Read Hobbs and Greene’s correspondence.

Courtesy of Harvard University Archives, UAV 607.5

So, why Harvard? Agnes’s cousin, Otto Falk, suggested a gift to Milwaukee-Downer College, because it was local, or to Marquette University, where Falk was a trustee. But Agnes ruled out Marquette, for being “too Catholic.” “The Pope might get a share,” she told one of her nurses, which may have been a reference to the increasing power of Polish Catholics in Milwaukee politics.

Agnes also decided against the University of Wisconsin at Madison, where Cyril had been a student, because it was dominated by the La Follettes. Robert La Follette, once the governor of Wisconsin and later a U.S. senator, disliked Lucius after the newspaper’s sometimes critical stance of La Follette’s politics, including his tax policies, which the paper said showed he represented monopolies rather than “the people.”

As for Harvard, there were some guesses. Harry Grant, who ran the Journal after Lucius became ill, spent two years as a student at Harvard. The Journal staff included several Harvard grads. Cyril’s father’s family had a long history at Harvard, though Agnes disliked Cyril’s father, who had abandoned her sister Hedwig. The truth is, aside from Mack’s affiliation, there was no obvious reason why she chose Harvard over several other universities.

Meanwhile, Harvard did not exactly welcome the bequest. First, journalists were not an obvious fit for Harvard, in part because many academics viewed them as undereducated tradespeople. Plus, the Great Depression was still in full swing, and schools were hard-pressed for funds. “The last thing I should have thought of asking Santa Claus to bring was an endowment to ‘promote and elevate the standards of journalism,’?” Conant later wrote. “Here was a very large sum of money which was tied up in perpetuity by what looked like an impossible directive. How did one go about promoting and elevating the standards of journalism?”

A journalism school was quickly nixed. Conant considered the idea of creating writing programs for journalists and a collection of microfilms of newspapers from around country. But in the end, he relied on the advice of influential columnist and Harvard alum Walter Lippmann, among others, who was on the Board of Overseers and who argued that an “in-service fellowship” would create much-needed academic education for journalists. Lippmann then helped persuade the university’s governing board of the plan.

In announcing the Nieman Fellowship in 1938, Conant called it a “dubious experiment.” But over time his skepticism shifted, as the Fellowships became both hugely popular and well reviewed by editors whose reporters had returned from the experience. In his 1970 autobiography, Conant wrote that Agnes Wahl Nieman was an “ideal benefactor” and the Nieman Fellowship “an invention of which I am very proud.”

When her obituary ran on the front page of The Milwaukee Journal on February 5, 1936, the article stated that Agnes had “spent her entire life in the light cast by two men of outstanding personality”—her father and her husband. But her life and her legacy were far more than that. By leaving her money to Harvard, and allowing the administration to interpret her bequest largely how it wanted, she gave journalism one of its most significant gifts. More than 1,400 journalists (and counting) and their audiences benefit from the light Agnes Wahl Nieman sparked in the final days of her life.

Maggie Jones, NF ’12, is a contributing writer for The New York Times Magazine